The Trial of Chinggis Khan: A Classroom Simulation

Steve Buenning

Introduction

Motivating students to engage deeply with important issues is a cherished goal of any dedicated world history teacher. Well-designed simulations can help our students develop what Sam Wineburg calls "mature historical thought."1 By introducing selected primary and secondary sources, guiding independent research, and encouraging collaboration in small groups, we can put our students on center stage as they confront essential questions about our past.

Several such questions involve the role of the Mongols in world history. As Timothy May has written,

An empire arose in the steppes of Mongolia in the thirteenth century that forever changed the map of the world, opened intercontinental trade, spawned new nations, changed the course of leadership in two religions, and impacted history indirectly in a myriad of other ways. At its height, the Mongol Empire was the largest contiguous empire in history. . . . Although its impact on Eurasia during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries was enormous, the Mongol Empire's influence on the rest of the world—particularly its legacy—should not be ignored.2

These steppe nomads, who lived their lives on horseback, were key historical actors. In 2000, Time magazine proclaimed Chinggis Khan its "Person of the Thirteenth Century."3 His grandsons expanded the empire to its greatest extent; one of them, Kublai, settled down to found his own opulent dynasty in China.

To this day, the Mongols continue to inspire controversy. Were they bloodthirsty marauders, destroyers of cities, slayers of innocents? Or were they promoters of trade, supporters of cultural exchange, connectors of East and West?

The Mongols present an exciting opportunity to connect our students to the past. The challenges are threefold:

a. to convey information on the rise of the Mongols to political and economic power during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries;

b. to address divergent interpretations of the Mongols' historical role; and

c. to heighten interest in the topic by involving students as active participants in the learning process.

To heighten interest, Anthony Pattiz recommends "stimulation through simulation." Pattiz serves as social studies department chair at Sandy Creek High School in Tyrone, Georgia. Drawing on his own experience, Pattiz urges us to lead an intellectual adventure which "begins with a simple, yet important proposition that students are more likely to remember and understand the past if it is presented as a powerful shared experience in which they are active interpreters rather than merely as a laundry list of names, dates, and places to be recorded, memorized, and then quietly forgotten when the test is over."4

Pattiz uses a variety of historical simulations in his repertoire, including mock trials. Theodore Sizer, founder of the Coalition of Essential Schools, endorsed this approach.

A six-week course in European history, which I visited one summer, for example, was built around court cases, each argued by teams of students. I witnessed the final arguments of the Dreyfus trial, presided over in stern efficiency by a black-robed attorney who was the mother of one of the students. The competition was palpable, the arguments were well researched, and the students understood the dilemmas implicit in the case. These kids were engaged in serious ideas in a way that gave those ideas life and with an intensity that assured their retention and their impact.5

There are numerous trial simulations currently available to the world history instructor. Pattiz himself has contributed one on the Tokyo war crimes trials (1946–1948).6 Using a simple Internet search, a teacher can turn up simulated trials of Christopher Columbus and Adolf Hitler on charges of crimes against humanity. Interact, a division of Social Studies School Service, publishes recreated simulations of the trials of Galileo, Joan of Arc, Louis XVI, Martin Luther, and Socrates.7 When I was teaching AP European History, my students tried Louis XIV on a charge of tyranny. That simulation continues to be used by my colleagues today.

Chinggis Khan and his descendants have become defendants in my AP World History classroom, which annually transforms into "The Court of History." There the Mongol leaders face indictment on a charge that they were uncivilized conquerors and rulers in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries (Appendix A). Sharon Cohen of Springbrook High School in Silver Spring, Maryland, provided inspiration and advice to help initiate this venture.8

The Mongols are useful as defendants for several reasons. First, from the unlikeliest of geographic origins, the Mongols rose to political and economic domination of the largest land empire the world has ever seen. Their matchless cavalry, relying on clever tactics and a well-earned reputation for ferocity, defeated much bigger forces and struck terror into countless hearts. As their successful armies enforced relative peace across the Eurasian steppes, long-distance trade and cross-cultural contacts increased.

Second, conflicting interpretations of their historical role make the Mongols attractive subjects for a mock trial. For many years, historians have viewed them "as barbaric plunderers intent merely to maim, slaughter, and destroy. This perception, based on Persian, Chinese, Russian, and other accounts . . . has shaped both Asian and Western images of the Mongols . . . ."9 As Gregory Guzman observes,

The early sources generally equate the barbarians with chaos and destruction. The barbarians are presented as evil and despicable intruders, associated only with burning, pillaging, and slaughtering, while the civilized peoples are portrayed as the good and righteous forces of stability, order, and progress.10

This view of the Mongols' historical role has prevailed for centuries.

However, recent scholarship has generated a different interpretation. This interpretation critiques the early sources as

. . . blatantly one-sided, biased accounts written by members of the civilized societies. Thus, throughout recorded history, barbarians have consistently received bad press—bad PR, to use the modern terminology. By definition, barbarians were illiterate, and thus they could not write their own version of events. All written records covering barbarian-civilized interaction come from the civilized peoples at war with the barbarians—often the sedentary peoples recently defeated and overwhelmed by those same barbarians.11

Such scholars as Morris Rossabi, David Morgan, and Timothy May have offered new perspectives.12 They have

. . . sought to present a more balanced picture of nomads' role in world history, emphasizing what they created as well as what they destroyed. These historians have highlighted the achievements of nomadic peoples, such as their adaptation to inhospitable environments; their technological innovations; . . . their role in fostering cross-cultural exchange; and their state-building efforts.13

As a result of these divergent interpretations, ample evidence exists to argue whether the Mongols were civilized or uncivilized conquerors and rulers during their heyday.

Third, the Mongols make wonderful defendants in a mock trial because their personalities and exploits trigger adolescent enthusiasm. For teenagers to become active participants in the learning process, they need a topic which fires their imaginations. The Mongols are ideal in this regard. Whether students are motivated by the Mongols' military prowess, hardiness under extreme conditions, grubby appearance, nasty reputation, open disregard for the conventions of "civilized" society, religious tolerance, or some other characteristic, the fact is that they remain intrigued by these steppe nomads. I have never had difficulty getting my students excited about participating in the trial of Chinggis Khan.

Planning the Trial

This trial is used in my AP World History classes. Presently eight days of class time are allocated for the simulation, with reflection essays due on a ninth day. While this is a substantial amount of time, within my course schedule, it is not excessive. First, since the Mongols play a uniquely crucial role in the span of world history, they deserve extra attention. Second, teaching about the Mongols dovetails with teaching about the Silk Roads and the Black Death. Third, careful planning allows me to devote these days to the trial without jeopardizing our progress toward the AP test in May. Fourth, the trial allows me to deal with issues of historical interpretation without being overly pedantic. Fifth, past and present students often tell me that the trial was the most enjoyable class activity of the entire school year. This reaction carries a lot of weight with me.

My class sizes have varied between fifteen and twenty-four students, but this simulation can be used in larger classes by adding witnesses or jury members. Additional witnesses could be: Chinese peasant, Ibn Battuta, Japanese daimyo, Korean noblewoman, Mongol general, or Tibetan Buddhist monk.

On the first day, students are introduced to the project, choose their roles, and begin their required reading. The second day is devoted to research in the computer lab. Days three and four are spent preparing in the classroom. The trial begins on the fifth day and proceeds through the seventh day. On the eighth day, the jury members report their verdicts, the teacher conducts a debriefing, and instructions are given for the reflection essays, which are due on the ninth day. The teacher guides students through each stage of the activity and plays the role of judge during the trial.

Before Day One, the teacher needs to become familiar with helpful sources. The teacher needs to be able to guide students so that they use their time efficiently in research. The sources on the assignment sheet (Appendix A) have been chosen so that students can readily find necessary information. Be sure to discuss all plans with your school's library media specialist; this professional should be your number one ally!

The Presentations tab on my website, www.sbuenning.com, allows users to download copies of all necessary documents. A helpful PowerPoint is also included.

Day One: Choosing Roles, Written Work, Required Reading

The Trial of Chinggis Khan assignment sheet (Appendix A) introduces the activity. There are four student roles in this simulation—attorneys, defendant, jurors, and witnesses—each of which requires different preparation and products.

The success of this activity depends on many factors, but one of the most important is the job done by the attorneys. Recruit quite reliable students for this role; they need to be intelligent, good speakers, and able to work with others. The attorneys function as the "team captains" of the prosecution and defense. They not only need to understand the logic and supporting details of their own case, but they also need to comprehend the opposing case. In addition, the attorneys must coordinate the testimony of the witnesses on their side of the issue, and be ready to cross-examine the other side's witnesses. Since the attorneys have such responsible roles, they are exempted from requirements for research papers and daily written journals. Offering abundant extra-credit enables me to recruit some very competent students to serve as attorneys.

Every student is expected to submit written work to the judge (teacher) at the start of the trial (Day 5). Attorneys provide lists of the direct examination questions which they intend to ask their own witnesses; these lists are also provided to the attorneys for the opposing side. The defendant (Chinggis Khan) writes a paper arguing that he and his descendants were civilized conquerors and rulers. The witnesses submit papers containing the testimony and supporting information which they plan to present under direct examination during the trial.

The jurors' required paper topics are chosen to help them begin to think about how other rulers led large states and armies during the premodern era. This task provides a frame of reference for evaluating the Mongol record from the perspective of its own time period. If additional jurors are needed, here are some more paper topics.

Tang Taizong of China: What Made Him a Successful Ruler?

Harun al-Rashid of the Abbasid Dynasty: Why Was He a Powerful Caliph?

Minamoto Yoritomo of Japan: How Did He Establish the Shogunate?

Mansa Musa of Mali: What Motivated His Behavior as a Ruler?

Louis IX of France: Saintly King or Ruthless Slayer of Muslims?

Edward I of England: How Did He Strengthen His Kingdom?

(During the trial, the juror does not take on the character of his/her paper topic. The juror is a twenty-first century high school student who develops and supports his/her own point of view concerning the issues of the case, based on the evidence presented in court.)

Once the student roles have been chosen, required reading (Appendix A) can begin. Required readings include a textbook excerpt, magazine article, and transcript of a website excerpt. In my opinion, the Bulliet text does a first-rate job in preparing students for the trial; the Strayer text is also excellent.14

|

|||

| Members of "The Court of History" | |||

Day Two: Research

Along with the required readings, Appendix A lists recommended sources, which students will find quite useful. Copies of the books are available for my students to use during class time or to check out overnight. The primary source collections are photocopied and distributed to students.

On preparation days, think about spending one day (no more) in the computer lab, but not because students are likely to find better sources there. The required and recommended sources on the assignment sheet contain information that is more than ample. However, students will want to look at online sources anyway, so you might as well let them find out for themselves that Appendix A is their best bet.

Avoid Wikipedia, which is not peer-reviewed and, in a general disclaimer, makes no guarantee of its own validity.15

Days Three and Four: Preparation

These days, set aside for further individual research, are also when the attorneys have a chance to talk with their own witnesses (P = prosecution, D = defense). Distribute the handout "Some Advice for 'The Court of History'" (Appendix B) and ask the attorneys and witnesses to read it. Facilitate dialogue and team-building by having prosecution and defense attorneys sit in different parts of the room, together with the witnesses for their side of the case. In order to present a coherent case, the attorneys and witnesses need to communicate with each other. The witness shares what he/she has learned about a character's actions and point of view, thus giving the attorney an opportunity to configure the witness' testimony within the framework of the entire case.

The attorney depends upon the witness, because the details of the case cannot be understood unless the attorney knows what information the witness can supply. Both prosecution and defense may call upon nine witnesses; the defendant is a defense witness. Attorneys for each side may ask a total of no more than twelve questions under direct examination, so these questions must be carefully chosen.

Review the trial procedures (Appendix A) with students. Remind students that all written work will be due at the start of the period on Day 5. Encourage students to appear in costume during the trial, if they wish.

|

|||

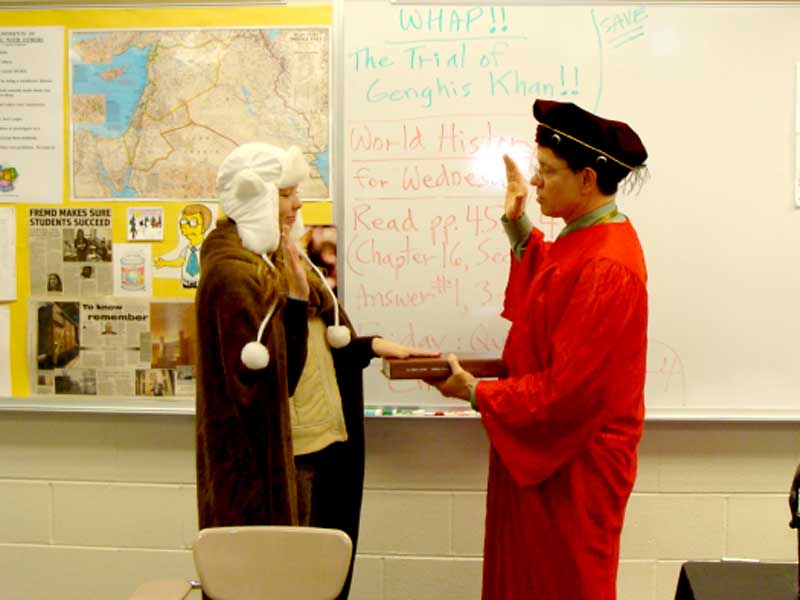

| Chinggis Khan is sworn in | |||

Days Five, Six, and Seven: The Trial

At the start of Day Five, the teacher (judge) collects the attorney questions, defendant and juror research papers, and witness sheets. On each day, the teacher distributes the daily written journals (see website) to defendant, jurors, and witnesses, who will complete the journals and submit them to the teacher at the end of each period.

The judge's call to order starts the trial on Day 5. The judge's responsibilities are to see that procedures are efficiently followed. Since the number of attorney questions is limited and since objections are not allowed, the trial should move along nicely. Generally, on the first day, you should be able to get through opening statements as well as direct and cross-examination of one or two prosecution witnesses.

By the end of Day 7, all witnesses will have testified and closing statements will have been delivered. The judge will charge the jury to decide the case based on the evidence presented in court. He will remind the jury that the indictment accuses Chinggis Khan and his descendants of uncivilized behavior as conquerors and rulers. Then the case will be turned over to the jurors. Jurors will consider the evidence and will prepare individual written verdicts.

Day Eight: Verdicts, Debriefing, and Reflection Essay

Jurors will read their verdicts aloud to the court. The case will be decided by majority vote, unless an even-numbered panel results in a hung jury. All types of verdicts have emerged from this simulation: not guilty, guilty, and hung jury. After the verdicts are read, the judge adjourns the court. Collect the jurors' written verdicts.

In the debriefing, be sure to compliment students appropriately on their performances. This mock trial is a difficult, lengthy (and enjoyable!) challenge for teenagers. If your students perform up to their capacities, they deserve to hear lots of praise from their teacher!

Debriefing will certainly involve at least two key issues. The first issue is the nature of "civilized" behavior. The indictment charges Chinggis Khan and his descendants as uncivilized conquerors and rulers in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. What does it mean to be "civilized?" Does the word have the same meaning today as it did in the thirteenth century? Should the Mongols' actions be evaluated from the perspective of their own times or from a later, perhaps more "enlightened" perspective? Robert W. Strayer points out,

A less critical or judgmental posture toward the Mongols may also owe something to the "total wars" and genocides of the twentieth century, in which the mass slaughter of civilians became a strategy to induce enemy surrender. During the cold war, the United States and the Soviet Union were prepared, apparently, to obliterate each other's entire population with nuclear weapons in response to an attack. In light of this recent history, Mongol massacres may appear a little less unique. Historians living in the glass houses of contemporary societies are perhaps more reluctant to cast stones at the Mongols.16

A second issue resides in the concept of change and continuity over time. The indictment before "The Court of History" charges both Chinggis Khan and his descendants with uncivilized behavior. The simulation is complicated by the indictment's grouping together of several generations of Mongol leaders—not just Chinggis Khan—as defendants. This grouping was intentional. It compels thoughtful students to ask good historical questions about the relationship of means to ends overtime. What was similar and what was different about the actions of Chinggis and, for example, his grandson Kublai? What were the reasons for those similarities and differences? How is an empire conquered? How is an empire ruled?

Following the debriefing, review with students the instructions for the reflection essay, which is due the next day. The purpose of the reflection essay is to provide an opportunity for students to think closely about the issues raised in the trial.

Assessment

In my classroom, The Trial of Chinggis Khan counts as a 50-point grade the same number of possible points as an AP-style essay). Points earned are based on:

- performance of the role in the trial (15 points);

- the quality of the research paper/witness sheet/written verdict (10 points);

- the quality of the daily written journal (10 points); and

- the quality of the reflection essay (15 points).

|

|||

| Mongol Woman prepares testimony | |||

Conclusion

Over the years, the high quality of student performances and their substantial enthusiasm in class (and afterward) lead me to believe that this simulation is a valuable learning experience. The Trial of Chinggis Khan helps to move students toward a meaningful, memorable encounter with important historical issues emerging from the actions of Eurasian steppe nomads eight hundred years ago. Wineburg observes,

Mature historical knowing teaches us . . . to go beyond our brief life, and to go beyond the fleeting moment in human history into which we have been born. History educates ("leads outward" in the Latin) in the deepest sense. Of the subjects in the . . . curriculum, it is the best at teaching . . . humility in the face of our limited ability to know, and awe in the face of the expanse of human history.17

The Mongols were quite unlike us in so many ways, and yet they still have much to teach our students in the twenty-first century.

Biographical Note

Steve Buenning, a National Board Certified Teacher and AP World History exam reader, teaches at William Fremd High School, Palatine, Illinois. He is author of The Russian Revolution, a teaching unit published by the Choices for the 21st Century Education Program at Brown University. He contributed a chapter to Teaching World History in the Twenty-first Century, edited by Heidi Roupp (M.E. Sharpe, 2010). He can be reached at sbuenning@d211.org.

Appendix A: THE TRIAL OF CHINGGIS KHAN (50 points)

Chinggis Khan founded the Mongol Empire, the largest contiguous land empire in world history. But was he civilized? Now, you will decide this issue as Chinggis Khan goes on trial before "The Court of History"!

The Indictment: Chinggis Khan and his descendants were uncivilized conquerors and rulers in the 13th and 14th centuries.

Roles

Attorneys (4) — (up to 20 extra-credit points are available)

Prosecution attorneys (2): P

"Team captains" of the prosecution. Will try to convince jurors that the evidence supports the indictment. Will study the evidence and organize the case.

Defense attorneys (2): D

"Team captains" of the defense. Will try to convince jurors that the evidence does not support the indictment. Will study the evidence and organize the case.

On the first day of the trial, both teams must give copies of their direct examination questions to the judge/teacher.

Defendant (1)

Chinggis Khan: D

Will testify at the trial. Will research and write a 2–3 page paper on this topic: "Chinggis Khan and his descendants were civilized conquerors and rulers in the 13th and 14th centuries." Paper will be typed (no larger than 12-pt.) and double-spaced. At least five sources will be correctly listed in a bibliography. Will compile a daily written journal of the proceedings (due to teacher after each day of the trial).

Jurors (2)

Will listen to each side make its presentation of evidence and finally issue a verdict. Will compile a daily written journal of the proceedings (due to teacher after each day of the trial). Will prepare a formal essay explaining the reasons for your own individual verdict, due the next school day after the trial. Will prepare a 1–2 page paper [typed (no larger than 12-pt.), double-spaced, at least three sources correctly listed in a bibliography] on one of these topics:

a.Timur the Lame (Tamerlane): Was He a Civilized Conqueror and Ruler?

b. Alexander Nevskii: His Relationship With the Mongols

Jurors will also be responsible for decorating the classroom for the trial.

Witnesses (17)

Will testify at the trial. Will prepare a 1–2 page witness sheet [typed (no larger than 12-pt.), double-spaced, with sources correctly listed in a bibliography.]

Will compile a daily written journal of the proceedings (due to teacher after each day of the trial).

1. Mongol warrior: D

2. Mongol woman: D

3. Kublai Khan: D

4. Historian Juvaini: D

5. Historian Rashid al-Din: D

6. Marco Polo: D

7. Silk Road merchant: D

8. Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, Persian philosopher/scientist/mathematician: D

9. Balkh shopkeeper: P

10. Historian Ibn al-Athir: P

11. Pope Innocent IV: P

12. Qutuz, Mamluk sultan of Egypt: P

13. Mstislav III, prince of Kiev: P

14. Mustasim, caliph of Baghdad: P

15. Chinese Confucian scholar: P

16. Chinese soldier: P

17. Muhammad II, sultan of Khwarazm: P

NOTE: All papers/witness sheets are due at the start of class on the first day of the trial. E-mail teacher if you know you will be absent on any day of the trial. If absence occurs, expect to be assigned a paper (due the next day) related to your role in the trial. Wikipedia must not be used as a source in this trial.

Procedures

- The judge reads the indictment. The defendant enters his plea.

- Opening statements by prosecution and defense attorneys (each side: 1–2 min.)

- Direct

examination: Prosecution calls 9 witnesses (inc. defendant).

(max. 12 questions total) - Defense cross-examines each witness. (max. 12 questions total)

- Direct examination: Defense calls 9 witnesses. (max.12 questions total)

- Prosecution cross-examines each witness. (max.12 questions total)

- Closing statements by prosecution and defense attorneys (each side: 1–2 min.)

- Jury deliberation and verdict (to be read in court on first school day after the trial).

Reflection Essay

Due on the next class day after the verdict is delivered, the reflection essay must be no less than 2 full pages long (typed and double-spaced). Handwritten essays will not be accepted. The essay should appear in type no larger than 12-point. The content of the essay will vary depending upon your role in the trial.

Attorneys:

1. The first half of the essay will address these questions:

a. Which one of your witnesses presented the most convincing evidence supporting your side of the case? Discuss specific reasons for your opinion.

b. Which one of the opposing witnesses presented the most convincing evidence supporting the other side of the case? Discuss specific reasons for your opinion.

2. The second half of the essay will address these questions:

a. Which aspects of the simulation were the most helpful to you? Discuss specific reasons for your opinion.

b. Which aspects of the simulation could be improved or changed? Discuss specific reasons for your opinion.

Witnesses and Defendant:

1. The first half of the essay will address this question:

Which two witnesses on the other side of the case presented the most convincing evidence? Discuss specific reasons for your opinion.

2. The second half of the essay will address this question:

In your own opinion (as a twenty-first century student), were Chinggis Khan and his descendants uncivilized conquerors and rulers in the 13th and 14th centuries? Discuss specific reasons for your opinion.

Jurors:

1. The first half of the essay will address these questions:

a. Which one of the prosecution witnesses presented the most convincing evidence supporting that side of the case? Discuss specific reasons for your opinion.

b. Which one of the defense witnesses presented the most convincing evidence supporting that side of the case? Discuss specific reasons for your opinion.

2. The second half of the essay will address these questions:

a. Which aspects of the simulation were the most valuable? Discuss specific reasons for your opinion.

b. Which aspects of the simulation could be improved or changed? Discuss specific reasons for your opinion.

Required Readings (for all students)

Bulliet, Richard W. et al. The Earth and Its Peoples: A Global History, 4th ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2008. pp. 323–340, 344.

or

Strayer, Robert W. Ways of the World. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2011. pp. 529–548.

Chua-Eoan, Howard. "Genghis Khan." <http://www.time.com> (handout)

"The Mongols in World History," <http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/mongols> (handout)

Recommended Sources

Books

Chambers, James. The Devil's Horsemen: The Mongol Invasion of Europe. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1979.

Fitzhugh, William W., Morris Rossabi, and William Honeychurch, eds. Genghis Khan and the Mongol Empire. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2009.

May, Timothy. The Mongol Art of War. Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2007.

Ratchnevsky, Paul. Genghis Khan: His Life and Legacy. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 1991.

Rossabi, Morris. Khubilai Khan: His Life and Times, 2nd ed. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009.

Weatherford, Jack. Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World. New York: Crown Publishers, 2004.

Primary Source Collections

Andrea, Alfred J., and James H. Overfield, eds. The Human Record: Sources of Global History, 5th ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2005. Vol. I, pp. 429–440.

Rogers, Perry M., ed. Aspects of World Civilization. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 2003. Vol. I, pp. 272–278.

Assessment

The Trial of Chinggis Khan counts as a 50-point grade. Points earned are based on:

- performance of the role in the trial (15 points);

- the quality of the research paper/witness sheet/written verdict (10 points);

- the quality of the daily written journal (10 points); and

- the quality of the reflection essay (15 points).

Appendix B: Some Advice for "The Court of History"

Attorneys

1. Work closely with your partner and divide the workload fairly.

2. Remember that you are "team captains." Work with all witnesses on your team to make sure that communication is clear and that the testimony is coordinated.

3. Work with witnesses in preparing questions. Remember that there are limits on how many questions may be asked during direct examination and cross-examination. These limits will be enforced by the judge.

4. Opening/closing statements should be clear and concise. Do not exceed time limits.

5. On the first day of the trial, give the judge two copies of your direct examination questions. The judge will keep one copy and give one copy to the opposing side.

Witnesses

1. Work closely with your attorneys. Exchange personal contact information and be available for necessary conferences with teammates prior to the trial.

2. Write a witness sheet that clearly identifies your character and his/her connection to Chinggis Khan and/or his descendants. The witness sheet should contain the testimony you plan to deliver at the trial.

3. When on the witness stand, make sure you are audible—if you tend to be soft-spoken, this is one time you need to speak louder! Maintain eye contact with the attorneys and jury.

4. Answer questions accurately and directly.

5. On the first day of the trial, bring three copies of your witness sheet: one for yourself, one for your attorneys, and one for the judge. Follow directions concerning format and list sources correctly in your bibliography (bibliography is an extra page, not one of the witness sheet's required 1–2 pages).

6. Compile a daily written journal of each day's proceedings, due to the judge at the end of class.

To Attorneys and Witnesses

1. Bring all necessary papers with you to the courtroom. On the days of the trial, you will not be allowed to print documents from the computer in the courtroom.

2. The judge will carefully monitor the proceedings for historical accuracy. If an attorney or witness makes an honest but important mistake, the judge will correct it swiftly and diplomatically. Minor errors will remain uncorrected. Therefore, objections from the attorneys will be unnecessary.

3. If you have any questions, please ask your teacher, either in school or via email.

1 Sam Wineburg, Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts: Charting the Future of Teaching the Past. (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2001), 5.

2 Timothy May, "The Mongol Empire in World History," World History Connected 5 no.2 (Feb. 2008), 1 http://worldhistoryconnected.press.illinois.edu/ Accessed 15 June 2011.

3 Howard Chua-Eoan, "Genghis Khan," Time, 31 December 1999 http://www.time.com/ Accessed 25 November 2008.

4 Anthony Pattiz, "Stimulation Through Simulation: Creating an Excellent Adventure as Students Have a Blast With the Past," World History Connected 5 no. 1 (Oct. 2007), 3. http://worldhistoryconnected.press.illinois.edu/ Accessed 20 June 2011.

5 Theodore Sizer, Horace's Hope: What Works for the American High School (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1996).

6 Anthony Pattiz, "Using a Japanese War Crime Trial Simulation to Expand Students' Understanding of the Roots of Wartime Atrocities, Mass Killing and Genocide," World History Connected 6 no. 3 (Oct. 2009). http://worldhistoryconnected.press.illinois.edu/ Accessed 20 June 2011.

7 http://www.interact-simulations.com/

8 Sharon Cohen, AP World History Teacher's Guide (New York: College Board, 2007), 16–18.

9 Morris Rossabi, "The Mongols in World History," 1 Asia for Educators Program, Columbia University http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/mongols Accessed 25 November 2008.

10 Gregory Guzman, "Were the Barbarians a Negative or Positive Factor in Ancient and Medieval History?" The Historian 50 (August 1988), 558.

11 Guzman, 559.

12 Morris Rossabi, Khubilai Khan: His Life and Times, 2nd ed (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009); David Morgan, The Mongols, 2nd ed. (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2007); Timothy May, The Mongol Art of War: Chinggis Khan and the Mongol Military System. (Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2007).

13 Robert W. Strayer, Ways of the World. (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2011), 548.

14 Richard W. Bulliet et al. The Earth and Its Peoples, 4th ed. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2008), 323–340, 344.; Strayer, Ways of the World, 529–548.

15 General disclaimer, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia.

16 Strayer, Ways of the World, 548.

17 Wineburg, Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts, 24.