John Brown: A Black Female Soldier in the Royal African Company

Dr. Steve Murdoch

University of St Andrews

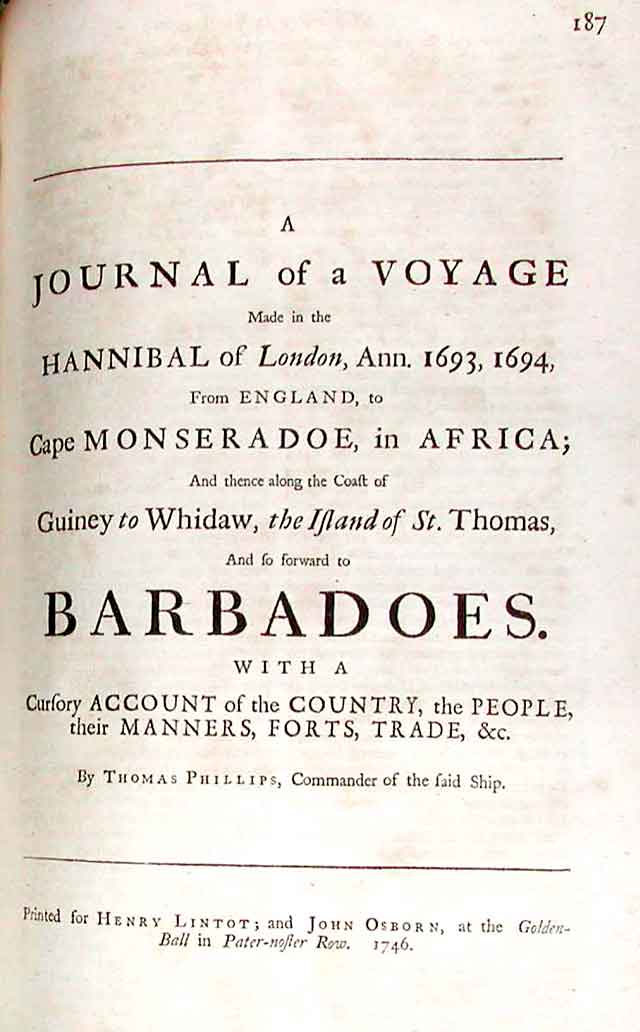

[Originally published in World History Connected, Vol. 1 No. 2: May 2004]

John Brown was the chosen name of a young black woman who disguised herself as a man and enlisted herself in London as a soldier in the Royal African Company of England, a company renowned for exploiting the slave trade between West Africa and Barbados.1 Her subsequent passage from England to Guinea on board the ship The Hannibal of London in 1693 is of interest to historians from many disciplines.2 However, for those with an interest in race, gender, or ethnicity in the Atlantic World, the ship's journal left to us by her commander, Thomas Phillips, is of particular importance.3 Indeed, although his journal entries actually tell us more about Commander Phillips than they do about John Brown, both figures provide fascinating glimpses into seventeenth-century attitudes toward these topics. Among Phillips's entries for November 1693 are the following:

Friday the 17th. These twenty-four hours we have had the wind various, at S. and S. by W. Yesterday we tack'd to the W. lying W. by S. and at two this morning it blowing a hard gale, we handed both our top-sails. Latitude, by reckoning, 32Á 47Ç N. Total westing 698Ç.

Saturday the 18th. These twenty-four hours we have had very squally weather, and many heavy showers of rain, wind shuffling between the W.S.W. and S.S.W. hard gale and great sea, course various, made difference of latitude seventy-three miles S. Departure 15 EÇ. Latitude, by reckoning, 31Á 34Ç N. Total westing 683 miles. This morning we found out that one of the Royal African Company's soldiers, for their castles in Guiney, was a woman, who had enter'd herself into their service under the name of John Brown, without the least suspicion, and had been three months on board without any mistrust, lying always among the other passengers, and being as handy and ready to do any work as any of them: and I believe she had continu'd undiscover'd till our arrival in Africa, had not she fallen very sick, which occasion'd our surgeon to visit her, and ordered her a glister:4 which when his mate went to administer, he was surpriz'd to find more sally-ports than he expected, which occasion'd him to make a farther inquiry, which, as well as her confession, manifesting the truth of her sex, he came to acquaint me of it, whereupon, in charity, as well as in respect to her sex, I ordered her a private lodging apart from the men, and gave the taylor some ordinary stuffs to make her woman's cloaths; in recompence for which she prov'd very useful in washing my linen, and doing what else she could, till we deliver'd her with the rest at Cape-Coast castle. She was about twenty years old, and a likely black girl.5

Sunday the 19th. From noon yesterday we have had the wind from S.W. to W. by S. lying up for the most part S. by W. fine top sail gale, and smooth water. Distance run per log is 132Ç. Had good observation of the latitude, which was 29Á 58Ç Total westing 669 miles.6

We had about 12 negroes who did wilfully drown themselves, and others starv'd themselves to death, for 'tis their belief that when they die they return home to their own country and friends again. I have been inform'd that some commanders have cut off the legs or arms of the most wilful, to terrify the rest, for they believe if they lose a member, they cannot return home again: I was advised by some of my officers to do the same, but I could not be perswaded to entertain the least thoughts of it, much less to put in practice such barbarity and cruelty to poor creatures, who, excepting their want of Christianity and true religion, (their misfortune more than fault) are as much the works of God's hands, and no doubt as dear to him as ourselves; nor can I imagine why they should be despised for their colour, being what they cannot help, and the effect of the climate it has pleased God to appoint them. I can't think there is any intrinsick value in one colour more than another, nor that white is better than black, only we think it so because we are so, and are prone to judge favourably in our own case, as well as the blacks, who in odium of the colour, say, the devil is white, and so paint him.30

That which challenges the first place is the perpetuall force and constraints put on the blacks to trade no where but with the forts, & this prosecuted to such a height as panjarding of their goods, killing people from the forts, and brandering their persons.

To remedy these evills it may be thought necessary to order that no manner of violence should be offered the blacks, but that they may be left free as to our molesting them to goe as they would themselves; but then, not to seem supinely to neglect the trade, that proper methods should be taken [ƒ] that they might oblige their people to come first to the forts with their slaves, & that what should be refused there the black should be left to his liberty to seeke his markett.

The advantages that would arise to your servants by this method are first a handle to remove all the odium and aversion that the blacks have contracted to your trade by being ill used by your servants & what they now will complaine of their from their masters.32

But what the smallpox spar'd [of the slaves], the flux swept off, to our great regret, after all our pains and care to give them their messes in due order and season, keeping their lodgings as clean and sweet as possible, and enduring so much misery and stench so long among a parcel of creatures nastier than swine; and after all our expectations to be defeated by their mortality. No gold-finders can endure so much noisome slavery as they do who carry negroes; for those have some respite and satisfaction, but we endure twice the misery; and yet by their mortality our voyages are ruin'd, and we pine and fret ourselves to death, to think that we should undergo so much misery, and take so much pains to so little purpose.35

|

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

||||

Biographical Note: Steve Murdoch received his Ph.D. in History at the University of Aberdeen in 1998. He is currently directing a project on British and Irish migration and mobility within Northern Europe at the Research Institute for Irish and Scottish Studies, University of Aberdeen. He has written and edited numerous books, which include Britain, Denmark-Norway and the House of Stuart, 1603-1660 (2000), Scotland and the Thirty Years' War, 1618-1648 (2001), and as coeditor with Andrew Mackillop, Fighting for Identity: Scottish Military Experiences c.1550-1900 (2002) and Scottish Governors and Imperial Frontiers, c.1600-1800 (2003). He has also recently taken a position as lecturer in history at the University of St. Andrews.

Notes

1 Kenneth Gordan Davies, The Royal African Company (London: Longmans, Green, 1957); James A. Rawley, The Transatlantic Slave Trade: A History (New York: Norton, 1981); and Robin Law, ed., The English in West Africa: The Local Correspondence of the Royal African Company of England, 1681-1699, 2 vols. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997-2001).

2 The Hannibal of London was unusual in that she was actually owned by the Royal African Company. Usually the Company preferred to hire vessels to reduce costs. For more on hiring practices, see Rawley, The Transatlantic Slave Trade, 154; for more on The Hannibal in particular, see 274-75.

3 Thomas Phillips, "A Journal of a Voyage Made in the HANNIBAL of London, Ann. 1693, 1694 From England, to Cape MONSERADOE, in AFRICA; And thence along the Coast of Guiney to Whidaw, the Island of St. Thomas, And so forward to BARBADOES. WITH A Cursory ACCOUNT of the COUNTRY, the PEOPLE, Their MANNERS, FORTS, TRADE. &c.," in vol. 6 of A COLLECTION of Voyages and Travels, some Now first Printed from Original Manuscripts, others Now first Published in English. In SIX VOLUMES (London, 1746), 187-255. The edition consulted for this article is in the private collection of Alison Duncan and Will Joy in Edinburgh. The author is deeply grateful to them for the free access to their library and permission to reproduce pages from this important document.

4 The definition of this word is obscure, though from the context it must relate to some form of enema or rectal poultice.

5 The usual modern meaning of the word "likely" is "probable" and may throw up a red herring in this context as to whether she was "probably black." However, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, in the seventeenth century the more usual meanings were "strong and capable looking" or "comely and handsome." Today the use of the word to mean "spirited" still retains currency in Britain.

6 Phillips, "A Journal of a Voyage," 195.

7 On women who dressed as men to serve as soldiers or sailors, see Julie Wheelwright, Amazons and Military Maids: Women Who Dressed as Men in Pursuit of Life, Liberty, and Happiness (Boston: Pandora, 1989), 7-8. Wheelwright notes that the issue of gender disguise was one that found expression on the London stage in the seventeenth century. No less that eighty-nine out of three hundred plays performed in London between 1660 and 1700 contained roles in which women disguised as men to pursue a profession. Wheelwright also observes that the majority of actual recorded cases usually involved women disguised to serve as soldiers or sailors. See also Dianne Dugaw, Warrior Women and Popular Balladry, 1650-1850 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989). While concentrating on the representation of female warriors in popular ballads, this volume contains interesting information on actual cases of women serving as soldiers and sailors (see particularly 30-31 and 128-134). Some women of the period were more overt in their military aspirations, such as Marchioness Anna Hamilton who served as a colonel of a regiment she herself raised for the "Army of the Covenant" in Scotland in 1639. Her main purpose was to challenge her own son, General James Hamilton, who commanded the opposing British Army of Charles I. When his fleet sailed into the Firth of Forth (between Edinburgh and Fife), she is reported to have ridden "forth armed with a pistol, which she vowed to discharge upon her own son, if he offered to come ashore--a notable virago." See Edward M. Furgol, A Regimental History of the Covenanting Armies, 1639-1651 (Edinburgh: John Donald Publishers, 1990), 26.

8 On black sailors, see W. Jeffrey Bolster, Black Jacks: African American Seamen in the Age of Sail (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1997); and James Clyde Sellman, "Military, Blacks in the American," in Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, ed. Kwame Anthony Appiah and Henry Louis Gates Jr. (New York: Basic Civitas Books, 1999), 1304.

9 Felix V. Matos Rodriguez, "Women, Black, in the Colonial Hispanic Caribbean," in Appiah and Gates, Africana, 2013.

10 James Walvin, The Black Presence: A Documentary History of the Negro in England, 1555-1860 (New York: Schocken Books, 1971), 12-14, 61-62; and V. G. Kiernan, "Britons Old and New," in Immigrants and Minorities in British Society, ed. Colin Holmes (London: Allen and Unwin, 1978), 31-32.

11 James Walvin, Black and White: The Negro and English Society, 1555-1945 (London: Penguin Press, 1973), 10-11; and Kiernan, "Britons Old and New," 42.

12 Walvin, The Black Presence, 14, and Black and White, 10.

13 We may never know if she was African, West Indian, or born in Europe. It is surprising she did not confess her given name once her true gender was revealed. While only speculation, if Phillips did not use her given name because it was not of European origin, that points to an African origin for her. Alternatively, he may simply not have remembered her given name having known her as John Brown for so long.

14 Phillips, diary entry for 11 January 1694, near Cape Baxos, "A Journal of a Voyage," 211. This entry reads, "On the point going into the river, about a cable's length from it, is a negro town of about thirty or forty houses, the captain of which is Dick Lumley, as he calls himself, having taken that name from captain Lumley, an old commander that us'd the Guiney trade formerly."

15 Davies, The Royal African Company, 242.

16 James Nightingale to Royal African Company, Annamoboe, 21 February 1686, in Law, The English in West Africa, vol. 2, 157.

17 James Forte to Royal African Company, Accra, 16 March 1686, in Law, The English in West Africa, vol. 2, 271.

18 Davies, The Royal African Company, 254.

19 P. E. H. Hair and Robin Law, "The English in Western Africa to 1700," in The Origins of Empire, ed. Nicholas Canny, vol. 1 of The Oxford History of the British Empire (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 261.

20 Sellman, "Military, Blacks in the American," 1304.

21 Matos Rodriguez, "Women, Black, in the Colonial Hispanic Caribbean," 2013; and Walvin, Black and White, 10.

22 Davies, The Royal African Company, 242-44; and Law, The English in West Africa, passim.

23 "Report by the Lords of the Admiralty upon the Demands of the Merchants for Convoys and Cruisers," point no. 5, 4 September 1693, Calendar of State Papers Domestic, vol. 1693, 311.

24 The escape from non-enslaved "custodial confinement" through gender disguise is proposed in Dugaw, Warrior Women and Popular Balladry, 185.

25 Phillips, "A Journal of a Voyage," 195.

26 See Walvin, The Black Presence, 13.

27 Interestingly, Phillips does not record any comments from the rest of the crew that their erstwhile crewmate turned out to be a woman, nor any sort of unrest among the crew as a result of it.

28 For the numbers of slaves shipped, see Davies, The Royal African Company, 363. In 1687, John Carter at Whydaw on the Slave Coast noted that a slave commanded a price of some £21 sterling. See John Carter to Royal African Company, 6 January 1686/87, reprinted in Law, The English in West Africa, vol. 2, 337.

29 Governor [Francis] Russell to Lords of Trade and Plantations, 23 March 1695, Calendar of State Papers, Africa and West Indies, vol. 1693-1696, 447.

30 Phillips, diary entry for 21 May 1694, "A Journal of a Voyage," 235.

31 It is worthy of note here that the charge of "paganism" was one of the causes that led to the English seeking to expel the "Blackmoores" from England in 1601 rather than their color. See Kiernan, "Britons Old and New," 32.

32 John Snow's letter to the Royal African Company, 31 July 1705, reprinted in Davies, The Royal African Company, 367.

33 For reference to the "informal empire," see Hair and Law, "The English in Western Africa," 262.

34 Phillips, "A Journal of a Voyage," 253.

35 Phillips, diary entry for [?] November 1694, "A Journal of a Voyage," 253.

36 Some 850,000 European Christians are thought to have been enslaved by African Corsairs between 1580 and 1680. For more on this trade, see Stephen Clissold, The Barbary Slaves (Totowa N.J.: Rowman and Littlefield, 1977); and Robert C. Davis, Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coat, and Italy, 1500-1800 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003).

37 In the 1990s this was also horrifically demonstrated in Bosnia where three religious groups of people (Orthodox Christian "Serbs," Roman Catholic "Croatians," and Muslim "Bosnians"), all of the same Slavic Indo-European ethnic background, were bent on destroying each other's communities in a show of barbarity unequalled in Europe since World War II.

38 Robert Davis, "British Slaves on the Barbary Coast," BBC History Homepage, accessed 7 January 2003.

39 Dugaw suggests that the desire of women to serve in a martial capacity was not because they sought the "freedom" of men or for the sake of soldiering, but rather because they desired to "do and get what they want." See Warrior Women and Popular Balladry, 158.