FORUM:

Comparative Study of Genocide

Developing a Critical Comparative Genocide Method

Jason Bruner, Volker Benkert, Lauren Harris, Marcie Hutchinson, Anders Erik Lundin

|

|||

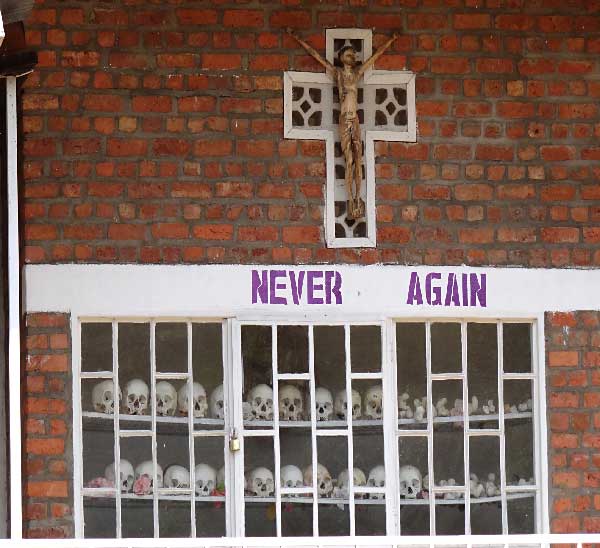

| Figure 1: "Never Again with Display of Skulls of Victims, Courtyard of Genocide Memorial Church, Karongi (Kibuye), Western Rwanda," Photograph by Adam Jones, Ph.D. (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.. | |||

Since it was coined by jurist Raphael Lemkin in the immediate context of the Holocaust, the term "genocide" has gained wide usage, not just as a description of those activities directly connected with the Holocaust itself, but also as a term that has been used to label events from various times and locales.1 The term's connection to the historical context of Europe in the mid-1940s raises the question of how such a category, developed in relation to a specific historical event, can be applied to diverse episodes. What factors and methods allow for this implicit comparison between the Holocaust and other cases of mass violence?

Certainly, it is redundant to suggest that genocide should be understood as a particular form of social evil, and thus worthy of naming. However, nations' discomfort at accepting the label as applied by the greater global community to events in their own history seems to indicate that the "evil" qualities of this activity, once so designated, in fact represent a commonly accepted demarcation for evil. In the end, it seems that many people would like to believe that genocide is a "thing that my ancestors could never do"2—or, one imagines, have turned a blind eye to. For these, and other, reasons, understandings of genocide can be vexing problems for international policy. Beneath the challenges posed by these problems lies the question of comparison. How closely must events resemble the Holocaust in order to be recognized as genocide? Is it possible to think comparatively about multiple genocides without creating hierarchies of suffering on the one hand and shallow parallels on the other?3

This article first establishes that comparative work is analytically and pedagogically crucial to the study of genocide, while arguing that survivor testimony is an essential and important source for grounding comparative work. We next suggest that digital humanities tools can facilitate comparative research on genocide testimony, and, finally, that these tools can be made pedagogically useful for teachers and students seeking to learn about various genocides. We maintain that this methodological combination can produce a comparative approach to the study of genocide that is both analytically rigorous to scholars as well as pedagogically accessible to students. For an example of an applied project using this methodology, please see the related essay in this volume: "Teaching, Learning, and Researching Genocide Comparatively."

We contend that the immediate aim of comparative studies in genocide should be to place occurrences like the Nazi slaughter of European Jews and other minority populations, the murder and displacement of American Indians, and the Rwandan Genocide on an equal footing, without incorporating them into one large and more obscure topic such as "tolerance" or "human rights." While remaining skeptical of grand narratives that universalize atrocities, researchers and educators can instead focus their attention on the individual experience of suffering, loss, resistance, and survival as expressed in survivor testimony, for it is the survivors whose experience bears witness to the content of these tragic episodes.

Genocide, Memory, and Comparison

There are various possibilities for approaching the comparative study of genocide survivor testimony. The representations could include textual, video, and audio testimonies, as well as those acquired in vastly different contexts: courtrooms, diaries, religious services, and oral histories, for example. Comparing these various forms of testimony necessitates engaging with a range of compositional contexts, in addition to a multiplicity of memory cultures and styles of memoriography. In some way, such a union of different memory cultures already exists, since Holocaust memory created the lexicon, scholarship, processes of working through the past, iconography, and even powerful number symbols for genocide. Peter Carrier even credits Holocaust memory as creating its own research genre, which he calls "Holocaust memoriography"––a theoretical understanding of history, language, and memory that heavily influences memory studies of other traumatic events.4 It is not clear, however, if this dominance of Holocaust memory culture is a blessing or a curse for other memory cultures. In fact, Samantha Power relates in her Pulitzer Prize-winning book how U.S. officials familiar with the Holocaust deliberately avoided using the term genocide with respect to Rwanda so as to not be compelled to take action.5 In his 1998 visit to Kigali, President Clinton publicly acknowledged this fact, stating: "[The United States] did not act quickly enough after the killing began. […] We did not immediately call these crimes by their rightful name: genocide."6 Nor does the integration of Holocaust memory into American master-narratives facilitate an equally close relationship between other genocides and American audiences. These problems of competing memory cultures and mainstream American self-perceptions speak directly to wider core humanities questions of collective memory and collective forgetting; historical justice activism; and representation in exhibitions, films, or sites of conscience and thus warrant further exploration.

Understanding the impact of diverse memorial cultures, however, also raises the question of how they integrate or refuse to integrate into American master-narratives and if they offer redemptive conclusions on the prevention of future atrocities. The placing of Holocaust memorials such as Nathan Rapoport's Liberation statue in Jersey City within sight of the Statue of Liberty, for example, suggests the successful interplay between elements of American ideals of liberty and pluralism and the memory of the Holocaust.7 In fact, Rapoport's statue of a G.I. carrying a Holocaust victim to safety does not only speak to Americans as liberators but also bears a redemptive message of how past suffering can be overcome through the preservation of liberty in this country.8 However, Native American memory cultures, while adopting the vocabulary of the Holocaust, do not only clash with the themes of liberty and pluralism––both of which were denied to them through U.S. policies and racialist discourses––but also offer few redemptive conclusions. The controversy around the Sand Creek Massacre memorial, for example, challenged one of the most redemptive readings of U.S. history by reminding Americans that the "Civil War midwifed not only 'a new birth of freedom', but also that it delivered the Indian Wars; that it was a moment of national redemption of some Americans, but of dispossession and subjugation for others."9

Considering diverse mass atrocities such as the Armenian Genocide in the late Ottoman Empire, the murder and displacement of Native Peoples in North America, the Holocaust, and the Rwandan Genocide––to name just a few––for universal patterns seems not only to be a useful approach for comprehending the term genocide, but furthermore, it seems to present a fairly equitable way to explore historical analogies while maintaining the unique tragedy inherent in each one. However, in this assertion researchers and educators must carefully consider the question of who––if anyone––bears ownership of the term genocide. Is the word simply to be viewed as indicating an event's similarity to the Holocaust? The vast array of contemporary patterns of the term's use would seem to contradict this notion.10 If particular events cannot claim a terminological ownership over the use of genocide, then researchers and educators are left to consider the ethical implications associated with laying claim to such a word in the case of the above-cited tragedies.

It follows, then, that we should ask: When should the term genocide be applied? And, along with that: To what end should we apply the term? These are not simple questions to answer, in part because the term genocide has taken on such political bulk that its application threatens to put enormous pressure on the so-called "international community" to intervene. Yet instead of spurring early intervention, it appears to make governments more reluctant to use a word that obligates them to action––a consideration that delayed responses to the Rwandan Genocide, as the earlier quote from President Bill Clinton suggests.11 On the other hand, the term has become a powerful tool for some communities. Certain Native American groups for instance, have taken to employing it for their purposes; in appropriating this and other aspects of the Holocaust, they have actually been able to draw greater attention to their specific plight. The basic contention made by these groups through their attempts is that the treatment of Native peoples in the Americas has amounted to genocide.12 The existence of such places as Fort Sumner in New Mexico––whose original function has elsewhere been described as essentially being that of a "concentration camp"––would certainly appear, on the one level, to justify specific comparison with the Holocaust.13 By utilizing the language of genocide these groups are seeking and, in some cases achieving, acknowledgment amidst the painful silence surrounding their pasts.14

If there exists reason for agreement on the comparative approach to genocide, there are also instances of clear resistance. For instance, while there are definite ideological similarities between the concepts of Nazi Lebensraum and Manifest Destiny, it is difficult to argue analogous intent to murder another people in each of these ideologies.15 This distinction becomes particularly important when asserting that settler colonialism16 in North America inevitably led to genocide.17 North American settler colonialism generated different manifestations of land theft, ethnic cleansing, and murder. Massacres such as those at Sand Creek and Wounded Knee were often, though not inevitably, the consequence of settler colonialism, and the more cooperative structures between indigenous peoples, the French and mixed-raced Metis18 in Canada are testimony to the variability of outcomes. Thus, genocidal massacres in these cases must be understood in the framework of a war of colonization and not necessarily as a war of extermination. This distinction makes these massacres different both from the Nazi conquest of the East, but also from other instances in U.S. history such as the war of extermination waged against Native Peoples in California during the Gold Rush.19 Parallels between the Holocaust and the murder and displacement of Native Americans are also complicated by the fact that cultural and eco-genocide committed against American Indians continued after the physical attack, whereas the German defeat in World War II ended the genocide, though not the persecution, of Jews in Europe. More rigid government bureaucracies, boarding schools, and new land laws that impoverished and urbanized many Native Americans even reinforced this renewed assault.20 This reinvigorated attack was also accompanied by ever more apologetic narratives in mainstream America, rendering any attempt to address the past in conjunction with whites impossible.

Since the Holocaust is often taken to be the paradigmatic genocide, and since common definitions of terminology are based on the Holocaust, it will likely continue to exact enormous influence on the understanding of genocide. This indebtedness to the Holocaust is evinced in later reactions to Rwanda, or by those who investigate acts of mass violence against American Indians. Don Fixico, for example, has identified four important ways that the Holocaust influenced perceptions and representations of the American Indian experience; namely, through: "1.) vocabulary and language, 2.) trauma history/studies, 3.) contextualization, and 4.) parallelism."21 Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart and Lemyra M. DeBruyn's assertion that American Indians suffer from unresolved historical trauma also used Holocaust-related vocabulary and post-memory trauma research. Strikingly, their suggestions for overcoming unresolved grief, however, are based on traditional ways of healing. In this case, the appropriation of language, the use of scholarly methods originating from the Holocaust, the context of other genocides or even the pitfalls of historical parallels did not replace traditional American Indian memory cultures––on the contrary, Yellow Horse Brave Heart and DeBruyn argue that they can reinforce such traditions and reinvigorate traditional notions of an interrelationship between the past, present, and the future.22 Research, therefore, should seek to reach a more intimate understanding of such interplay between different memory cultures. This intersection raises important questions on how Holocaust language and research can be utilized to analyze other instances of mass violence and their memory without imposition.

Similar problems can be said to mar comparisons between the Holocaust and the Rwandan Genocide. Arguments favoring the Holocaust's uniqueness, for instance, have often stressed the Nazis' ideological zeal to murder;23 the use of modern science, technology, and bureaucracies;24 or the mobilization of a large part of mainstream society to co-perpetrate or tolerate the murder as bystanders and beneficiaries.25 The ideology, modernity, and totality of the Holocaust have thus been used to denote Rwandan violence as "tribal" and anti-modern, thus reiterating condescending narratives of the colonial era.26 In this kind of reading, primordial ethnic conflict paired with racialist discourses imported by colonial powers were at the heart of the massacre of Tutsi and moderate Hutus, rather than political strife between rivaling elites who employed racialist discourses for political gain, as recent scholarship has argued.27 At the same time, both the Rwandan Genocide and the murder and displacement of Native Peoples in the United States relied on ideology, modern bureaucracies, and tacit support of ordinary people, albeit in different manifestations. It is true that if views supporting the uniqueness of the Holocaust run the risk of overlooking similar processes in other genocides, then their direct opposites––simplistic comparisons between different atrocities––bear the danger of inappropriate inference. In illustrating this reasonable concern over abstraction, Catharine and David Newbury have noted that in order for

conditions in Europe of the 1930s to be seen as parallel to those of Rwanda in the 1990s […] Germany would have to have been ruled by an exclusive Jewish minority for several hundred years; that Jewish minority would have been overthrown 30 years before the Holocaust and throughout that time maneuvered to regain power.28

In developing their comparative methods, researchers must be sensitive of these distinctions between genocides, and seek to maintain them while still locating similarities among genocides.

Given these complications, it seems appropriate to suggest that a key step in determining a normative pattern for designation would be to locate which characteristics distinguish genocide broadly as a category despite these varying manifestations; there must be relatively comparable sources across atrocities from which comparable characteristics can be derived. Since we have already noted that it was the horror of the Holocaust that not only generated the term, but also the need to include or exclude other atrocities, it certainly seems like an obvious starting point of investigation. Of course, concerns over the Holocaust's primacy might also influence the way our understanding of each subsequent categorization evolves. Again, in the early days of the Rwandan crisis, we have already shown that Western officials tragically refrained from calling the murder they saw genocide, in part because it seemed incomparable to the Holocaust, which made decisive intervention highly unlikely.

Comparing Through Survivor Testimony

Testimony can come in different forms, including as ego-documents (e.g., diaries and memoirs), official documents (e.g., court testimony or UN commission reports), interviews, or documents intended for specific audiences (e.g., letters or literary works). Even in the absence of an intended audience, the narrators will convey not only the immediacy of the story, but also their emotions as they lived through past horrors again while relating them. Of course, the events and emotions conveyed are as manifold as the people who tell them. Yet, basic emotions such as fear, social isolation, flight, failure to comprehend the baseness of the perpetrators, and hope for help are universal and appear widely in testimonies, despite their obvious differences in experiences, cultural backgrounds, and manner of rendition. Likewise, as readers and listeners, our own emotions of sympathy, shock, disbelief, horror, and hope for redemption in these stories are universal. Such comparison of emotions helps us understand how people react to atrocity beyond culturally coded dimensions. Yet, a broader understanding of the phenomenon of genocide requires more abstract categories equally universal to the experience as the emotions mentioned above. As such, we hope to take events and emotions as expressed in testimony on a more abstract analytical level of themes that speak to the distinctive nature of genocide. Without suggesting a taxonomy or succession of these categories, we feel that most genocides include common themes (that we discuss below), and our work relies on translating the emotions and events expressed in the testimony to these categories to allow for comparison.29

Although the pitfalls of both particularity and simplistic comparison of different genocides should be obvious, we want to suggest that a comparative framework can be built around common a series of themes present in the comments of survivors from diverse genocides; these themes include: prejudice, violence, survival, and resistance, as well as perpetrators, conformity, ideology, and coming to terms with the past (see related article, "Teaching, Learning, and Researching Genocide Comparatively"). While these themes are deeply engrained in the fabric of the cultural, social, and political context of persecution unique to each instance of mass violence, survivors telling their story touch on many of these themes with remarkable consistency. It appears, therefore, that survivor testimony—despite its diverse forms of collection and culturally dependent ways of rendering memory—is the key to delineating common, comparative themes between genocides.

As we have noted, comparison between disparate atrocities bears several underlying complications. One of these complications is that emphasizing the uniqueness or greater tragedy of one event over another might cause researchers to fail to see the particularity and individual horror of other atrocities. A second danger is the inverse possibility: that too much comparison might lead "to the point of abstraction and banality."30 Conceptual models built around generic terms like "modernity" or arguments concerned with simply demonstrating the "uniqueness" of a particular historical event do not necessarily foster constructive historical or contemporary engagement around the concept of genocide. Instead, researchers and educators could seek to outline common themes of genocide (like those mentioned above) from emotionally visceral sources. In this process, these themes ought not allow students and researchers to lose track of the unique individuality of these tragedies, even as the themes provide them with comparable data. In this regard, genocide survivors' testimonies are instrumental in determining the existence of these normative patterns within mass atrocities. Such testimonies not only have the capacity to compel the reader, viewer, or listener with enormous emotional power, but they also allow researchers to delineate common themes present in diverse accounts of genocides from different continents and time periods. In addition to relating immediate, personal experiences within larger historical processes, survivor testimony can also capture the process of imbuing the past with meaning and, in doing so, establish an identity across generational layers.31 This process of interpretation is often ambiguous and contested, because while individual testimony can reveal the deep despair that comes from the shattering of beliefs in human values, older survivors and later generations have a tendency to search for redemptive interpretations within their cultural contexts.32 As such, analyzing testimony does not only harness the explanatory and emotional power of oral testimony for comparative purposes, it also allows researchers and educators to contrast how different societies make sense of past horrors. Even though any mass violence remains embedded in the cultural context in which it occurred, survivor testimony can translate the communicative aspect of violence into broader themes that document persecution, resistance, and survival, among other common themes. Through the analysis of testimony and juxtaposition of testimony from other atrocities, researchers and educators can thus gain a comparative perspective drawn from those who survived these atrocities.

The Complications of Survivor Testimony

Utilizing testimony as the comparative framework for individual experiences of genocide, however, generates new methodological challenges, since there is no universal form of testimony across cultures or religious traditions and survivors construct and perform their testimonies in widely ranging forms and genres. Such a juxtaposition of oral testimony from different groups, cultures, and religions must also, therefore, bridge diverse memory cultures and consider their evolution over time, link various forms of rendition, and combine different media on which this testimony is stored. The scholarship, vocabulary, and representations of the Holocaust have proven to be influential scholarly tools, due in part to the fact that they are also compatible with American master-narratives and thus have gained traction beyond academia.33

Holocaust testimony and its uses are neither monolithic today nor have they been in the past. David Boder's recordings, taken directly after the war, for example, reveal the shock and trauma of Holocaust survivors and their growing fear to find their stories ignored by audiences trying to leave the past behind. Later Holocaust testimony, however, evolved to researched accounts that situate the personal experience in the context of scholarship, demonstrate greater societal awareness, and relate the experiences of the Holocaust to a new generation born to the survivors.34 If, for example, the international community understood the Rwandan Genocide in terms of the Holocaust, accounts from survivors of the Rwandan genocide rarely make this connection. However, not unlike the voices of Holocaust survivors Boder recorded, early testimonies from Rwanda are largely dominated by shock and trauma with few allusions to scholarship or cross-references to other accounts.35

Certainly the fact remains that the quality and extent of testimonies among atrocities can vary greatly with respect to cultural background of what survivors recount and how they recount it. Testimonies can differ also in terms of whom they address and what they consider "hearable" for their audience. Naturally, professional interviews, court testimony, family narrations, or diaries differ significantly in genre, but also in interaction with the audience, who in turn influence the testimony as well.36 Moreover, these testimonies are often rendered through various media, which raises a host of presentation questions. In short, such a comparative approach reveals the cultural differences around the "creation and re-creation of narratives […] and historical consciousness" over time and in different forms ("told, written or performed"), styles (literary or factual), and media.37 Projects utilizing a comparative approach, therefore, must be mindful of the diversity of both the tradition and the recording of testimony in instances of mass violence.

Those, for instance, interested in the testimony of individuals involved in the plight of the Native Americans have found that the chroniclers of the involved events often belonged to the same groups of people who were the persecutors.38 The struggle for recognition of Native American suffering was therefore one based mostly on oral traditions against American national narratives bolstered with a variety of sources that at worst glorified the conquest of the West and at best saw the end of federal policies on Native Americans as an event of national redemption.39 Furthermore, oral traditions themselves are, for Native Americans, not necessarily synonymous with oral histories since oral tradition actually relates not individual––but communal––history in a non-linear fashion that transcends the past-present-future continuum.40 Native American memory of persecution thus does not only conflict with mainstream American historical self-perceptions, its mostly oral traditions are also discordant to Western linear notions of history and research on testimony stemming from the field of Holocaust studies. This has led some scholars to question the validity of methodologies of academic disciplines in general and urge American Indian Studies to develop its own methods based on the oral tradition of indigenous peoples.41 But memory is always individual and collective, simultaneously firm and ambiguous, and yet never static and always negotiated in a communal forum. Despite these challenges, oral histories from survivors remain a compelling way to engage students and scholars in connecting these diverse atrocities in meaningful ways. What they require is an appropriate medium to provide guidance to individuals attempting to negotiate this complex terrain.

Conclusion

This essay's primary aim has been one of query and outline, providing significant questions regarding the development of comparative descriptive themes of genocide based upon survivor testimony. It further sought to determine how best those norms can be established so that educators might more accurately delineate those characteristics to students; students, in turn, would be given basic tools of comparative historical research and thinking so that they might apply the recognition of these patterns to future critical investigations.

In developing this analytical model for comparative genocide research, we have sought to address the complexity and diversity of survivor testimonies, recognizing the range of memoriographies, practices of testifying, and the diversity of contexts in which testimonies are recorded. We have developed a model that seeks to be mindful of both this range of source material as well as the practical limitations of historical pedagogy in high school classrooms. We contend that locating comparative themes amongst genocide survivor testimonies can avoid diminishing the emotional complexity of the particular testimony, resist the tendency to establish a hierarchy of sufferings between genocides, and preserve the specificity of individual experiences of mass violence. As a result, we contend that researching genocides comparatively in this way is not only an important pedagogical practice for historical educators, but, when done within a critical apparatus, can produce data and insights that can be of benefit to advanced researchers as well.42

Jason Bruner is an Assistant Professor of Religious Studies in the School of Historical, Philosophical, and Religious Studies at Arizona State University. His first book, Living Salvation in the East African Revival in Uganda, is forthcoming with University of Rochester Press. He can be reached at Jason.Bruner.1@asu.edu.

Volker Benkert is an Assistant Professor in the School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies at Arizona State University. His research focuses on the impact of sudden regime change on biographies after both totalitarian regimes in 20th century Germany. He can be reached at Volker.Benkert@asu.edu.

Marcie Hutchinson, after thirty-one years as a high school history teacher, is currently Director of K-12 Initiatives for the School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies (SHPRS) at Arizona State University. She has instructed ASU secondary education students in history teaching methods and is project coordinator, curriculum designer and presenter for Jazz from A to Z an interdisciplinary program of Mesa Arts Center and SHPRS in partnership with Jazz at Lincoln Center. He can be reached at Marcie.Hutchinson@asu.edu.

Lauren McArthur Harris is an Assistant Professor of History Education at Arizona State University. Her work focuses on issues in history/social studies teaching, learning, and curriculum, particularly related to world history. She can be reached at lharri14@asu.edu.

Anders Erik Lundin is graduate student pursing a Master's Degree at Yale Divinity School, where he is studying religion and media. Before that he wrote screenplays for short films.

1 "What is Genocide," United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, accessed August 18, 2015, http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10007043.

2 Turkey's denial of the category "genocide" to the mass violence committed against the Armenians in its history is the clearest example of such an occurrence, see for example Caleb Lauer, "For Turkey the denying an Armenian genocide is a question of identity," Al Jazeera America, last modified April 24, 2015, http://america.aljazeera.com/articles/2015/4/24/for-turks-acknowledging-an-armenian-genocide-undermines-national-identity.html.

3 Brenda Melendy, "World History Analysis and the Comparative Study of Genocide," World History Connected 9, no. 3 (2012).

4 Peter Carrier, "Holocaust Memoriography and the Impact of Memory on the Historiography of the Holocaust," in Writing the History of Memory, ed. Sefan Berger and Bill Niven (London: Bloomsburg, 2014), 200.

5 Samantha Power, A Problem from Hell. America and the Age of Genocide (New York: Basic, 2002), 351ff.

6 Quoted in Nigel Hamilton, Bill Clinton: Mastering the Presidency (New York: Public Affairs, 2007), 687.

7 James Young, The Texture of Memory. Holocaust Memorials and Meanings (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993), 319.

8 On redemption and the Holocaust, see: Saul Friedlander, Memory, History and the Extermination of the Jews of Europe (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993), 133.

9 Ari Kelman, A Misplaced Massacre. Struggling over the Memory of Sand Creek (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2013), 279.

10 Alan Rosenbaum, ed. Is the Holocaust Unique?: Perspectives on Comparative Genocide (Boulder: Perseus Books, 2001); Reinhart Kössler, "Genocide in Namibia, the Holocaust and the Issue of Colonialism," Journal of Southern African Studies 38:1 (2012): 233-238; David B. MacDonald, "Daring to Compare: Maori Holocaust," Journal of Genocide Research 5:3 (2003): 383-403; Tracey Banivanua-Mar, "'A thousand miles of cannibal lands': Imagining Away Genocide in The Re-colonization of West Papua," Journal of Genocide Research 10:4 (2008): 583-602.

11 David Scheffler, "Genocide and Atrocity Crimes," Genocide Studies and Prevention 1:3 (2006), 230.

12 Alex Alvarez, Native America and the Question of Genocide (Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, 2014), 167. This usage is not limited to Native Americans. See also MacDonald, "Daring to Compare: Maori Holocaust."

13 Sherry Robinson, Apache Voices: Their Stories of Survival as Told to Eve Ball (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2003), 122.

14 Alvarez, Native America, 167.

15 Björn Krondorfer, "Review of Carol P. Kakel III., The American West and the Nazi East: A Comparative and Interpretive Perspective," German Studies Review 37:1 (February 2014), 228.

16 By "settler colonialism," we generally refer to a process whereby a group of settlers lay claim to land and eventually become the minority and, in the process, engineer the removal or elimination of the original or previous inhabitants of that land, "except in nostalgia," as Nancy Shoemaker defined it. Nancy Shoemaker, "A Typology of Colonialism," Perspectives on History (October 2015).

17 Patrick Wolfe, "Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native," Journal of Genocide Research 8:4 (December 2006): 387-409.

18 The Metis were a people of mixed First Nations and French descent who were often seen as arbiters between both populations.

19 Alvarez, Native America, 112.

20 Elizabeth Cook-Lynn, Anti-Indianism in Modern America. A Voice from Tatekeya's Earth (Urbana-Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2001), 192.

21 Don Fixico, "American Indians View the Jewish Holocaust: Survival and Rebuilding," p. 3.

22 Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart and Lemyra M. DeBruyn, "The American Indian Holocaust: Healing Historical Unresolved Grief," The Journal of the National Center American Indian and Alaska Native Programs (June 1998), 74.

23 Steven T. Katz, "The Uniqueness of the Holocaust," in Alan Baumann, ed., Is the Holocaust Unique? Perspectives on Comparative Genocide (Philadelphia: Westview Press, 2009), 55.

24 Zygmund Baumann, Modernity and the Holocaust (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1989), 91.

25 Götz Aly, Hitler's Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State (New York: Metropolitan, 2007), 41.

26 Scott Strauss, "The Promise and the Limits of Comparison. The Holocaust and the 1994 Genocide in Rwanda," in Alan Rosenbaum, ed., Is the Holocaust Unique? Perspectives on Comparative Genocide (Philadelphia: Westview Press, 2009), 247.

27 Jay Carney, "Beyond Tribalism: The Hutu-Tutsi Question and Catholic Rhetoric in Colonial Rwanda," Journal of Religion in Africa 42 (2002), 173.

28 Catharine Newburg and David Newbury, "The Genocide in Rwanda and the Holocaust in Germany: Parallels and Pitfalls," Journal of Genocide Research 5:1 (2003), 140.

29 For an example of how to compare genocides using world history themes and methodologies, see Melendy, "World History Analysis."

30 John K. Roth, "The Ethics of Uniqueness," in Alan S. Rosenbaum ed., Is the Holocaust Unique? Perspectives on Comparative Genocide (Philadelphia: Westview Press, 2009), 31

31 Mary Marshall Clark, "The September 11 Oral History Project," in History and September 11th, ed. Joanne Meyerowitz (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2003), 124.

32 The most outspoken critic of redemptive responses to the Holocaust is Larry Langer, whose work is based on the Yale Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies. Larry Langer, Holocaust Testimonies. The Ruins of Memory (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991), 4.

33 Yellow Horse Brave Heart and DeBruyn, "The American Indian Holocaust."

34 Alan Rosen, The Wonder of Their Voices: The 1946 Holocaust Interviews of David Boder (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010).

35 For example in testimony collected by the United Nations on Rwanda: http://www.un.org/en/preventgenocide/rwanda/education/survivortestimonies.shtml

36 Alan Greenspan, "Survivors' Accounts," in Peter Hayes and John K. Roth ed., The Oxford Handbook of Holocaust Studies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 419.

37 Ramazan Araz et al., "Documenting and Interpreting Conflict through Oral History: A Working Guide" (Columbia University Center for Oral History, 2012), 2.

38 John McDemott, "Wounded Knee: Centennial Voices," South Dakota History 20 (1990): 245-298.

39 Ari Kelman, A Misplaced Massacre. Struggling over the Memory of Sand Creek (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2013).

40 Don Fixico, The American Indian Mind in a Linear World: American Indian Studies and Traditional Knowledge (New York: Routledge, 2003), 22

41 Elizabeth Cook-Lynn, Tom Holm, John Red Horse, and James Riding In, "Reclaiming American Indian Studies," Wicazo Sa Review 20:1 "Colonization/Decolonization, II" (Spring, 2005): 169-177.

42 Please also see Lauren McArthur Harris, Marcie Jergel Hutchinson, Volker Benkert, Jason Bruner, and Anders Erik Lundin, "Teaching, Learning, and Researching Genocide Comparatively," World History Connected 14, no. 2 (2017).