FORUM:

The Philippines and World History

Caquenga and Feminine Social Power in the Philippines

Steven James Fluckiger

The colonial history of the Philippines offers considerable insight into how the Spanish colonization of the Philippines witnessed the defeminization of Philippine society. The history shows that the initial Christianization of the islands saw the diminishment of important feminine privileges, such as spiritual and medicinal roles, as well as sexual liberties.1 The power of this trope has discouraged rather than stimulated deeper analysis by most world historians who have minimal expertise in both the subject and the locale in terms of research and limited classroom space in both time and devotion to gender studies of interest to students remote from their experience. This article is designed to demonstrate how, by looking deeper into the Philippine case, world historians can develop a more profound understanding of gendered colonial relations that can inform their comparative research and also render it more attractive to contemporary students. It seeks to do so through as case study of an indigenous Philippine woman named Caquenga that reveals how powerful some women were in the precolonial and early colonial period.

Caquenga's rebellion is a single instance in early colonial Philippine history that exposes the social power and influence indigenous women held in precolonial and early colonial societies. This feminine social power is the influence precolonial and early colonial Philippine women held in their societies over other indigenous Philippine people, both men and women. Women expressed this social power through their position in society, which could be through their economic class, their spiritual authority in indigenous animism, or their standing in local politics.2 Caquenga's revolt, coupled with other Prehispanic and early Hispanic examples, not only show that women had a considerable amount of social power, but that their social power could supersede the political power of their male leaders.

Several scholars of Prehispanic and early colonial Philippines agree upon the widespread dominance of women in animism and the influence they held. A majority of animist leaders were female. Many times, biologically male persons participated as spiritual leaders as well, but more often in effeminate roles rather than as masculine figures. This was common throughout the islands.3 For the sake of this paper, the feminine power wielded by these effeminate male figures will be grouped with the feminine power of their female counterparts due to their adoption the feminine, a theme supported Carolyn Brewer and J. Neil C. Garcia, two Philippine scholars.4 They will also be referred to by the s/he pronoun since definite gender identity cannot be determined through the Spanish sources.5 These effeminate male figures will also be referred to as bayogs, an indigenous term used in the Tagalog language.6 These female and bayog leaders were influential and dominated all the religious affairs of the barangays and local villages they resided in. The position of priestess (including the bayog) was an occupation, and they received compensation from work throughout the islands.7 They also dominated the realm of medicine, being the only source of medical care available to indigenous Philippine people before the arrival of the Spanish.8 Outside of religion and medicine, women experienced economic privileges, including the ability to own and inherit property. They also participated in the production of pottery and weaving, products frequently sold off.9 Women and the bayog were a powerful force in the Philippines before Spanish domination, a power that they slowly lost with the arrival of a male-dominated Catholic religion.10

Some of the research done on Prehispanic and early Hispanic Philippine society, however, centers power on the male-dominated political and war figures, often referred to as the datu. While histories often acknowledge the social power women held during this period as spiritual leaders, they underestimate their political and social power through oversimplified explanations of male-oriented leadership positions. Rigid descriptions of Prehispanic and early Hispanic gender roles implied that women were the sole holders of spiritual authority and men were the sole holders of political power, typically displaying the head of the barangay as the male datu. They make little mention, if any, of either gender crossing into the other gender's realm of power.11 Yet the account of the Cagayan priestess Caquenga and other indigenous feminine leaders show that women, too, could hold positions of political authority through their own derived social power, superseding the authority of their supposed male superiors.

Caquenga's Revolt

We can better understand the amount of social power precolonial and early colonial Philippine feminine figures held by examining the account of Caquenga, a Cagayan animist priestess who wielded a great amount of social power. The Cagayan River Valley is located in north-eastern portion of the island of Luzon. At the time of Spanish contact, the Ibanag and Kalinga peoples, among other ethnic groups, dominated the valley and had trade relations with various ethnic groups in the mountain regions to the west. The valley attracted the Spanish to establish a diocese in Cagayan, called the Nueva Segovia diocese, because of its rich rice fields and access to gold from the trade network with the peoples in the mountains.12

|

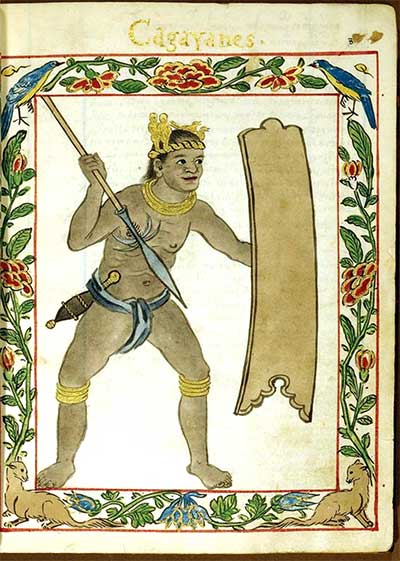

|||

| Figure 1: European depiction of a male Cagayan warrior. The image comes from the Boxer Codex, a sixteenth-century work describing the various peoples of the Philippine Islands as well as other East Asian and Southeast Asian polities. The author is unknown, but the work contains a wealth of knowledge regarding European observations of the early colonial Philippine people.13 Courtesy Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana. | |||

The source comes from Historia de la Provincia del Sancto Rosario de la Orden de Predicadores written by Fray Diego Aduarte. It is a history of the Christianization of the Philippine Islands performed by the Dominican Catholic order. This work was meant to document Dominican missionaries in converting indigenous Philippine people and the establishment of the Dominican order and their affiliated churches on the islands.14 The history, written by a Dominican for the purpose of promoting the cause of the Dominicans, of course, is subject to its own flaws and biases. However, it contains the only available primary reference, to my knowledge, of Caquenga, her rebellion, and Catholic responses.

Aduarte recounted the establishment of the Dominican Order in the Philippines, as well as the creation of the Nueva Segovia diocese in the Cagayan valley. The story began in 1607. The establishment of the diocese in Nueva Segovia in 1595 attracted the attention of Catholic clergy throughout the colony and the world because of the increase need for priests and missionaries to sustain the diocese. A certain Fray Pedro came to the diocese and began proselytizing along the northeastern coasts of Luzon. During his tenure at Nueva Segovia, a Cagayan village leader named Pagulayan caught his attention. For years Pagulayan petitioned the diocese to send a missionary to visit his remote village further south, but the clergymen were too busy to travel that far. After his visit with the leader, Pedro decided to honor his request and went to Nalfotan, Pagulayan's village. The village, per the Dominican history, was the chief village of the Malagueg people, known today as Malaweg.15

The condition of Nalfotan astounded Pedro when he arrived. The Malagueg already erected a church, even though there was no official European presence in the village. His arrival caught the attention of men, women, and children throughout the village who gathered to be instructed on what they needed to do next to join in the Catholic faith. Pedro, on discovering the willingness and readiness of Pagulayan's people to accept the Catholic faith, chose to work with the people in the village. Through his effort and the help of Pagulayan, he successfully established an official Catholic presence in Nalfotan.

|

|||

| Figure 2: Image of the Saint Raymond of Peñafort Parish Church in modern-day Rizal, Cagayan, formerly Nalfotan. This pictured church's cornerstone was laid in 1617, ten years after Fray Pedro's arrival to Nalfotan. Named after the thirteenth-century Catalan Dominican friar, canonized in 1601, who converted several Muslims to Catholicism. The name produces layered imagery, as many indigenous Philippine people adopted Islam before the advent of the Spanish. The Cagayans, however, were never introduced to Islam.16 | |||

In the midst of this religious triumph, some of the Malagueg clung onto their Prehispanic traditions. One priestess named Caquenga held fast to her original religious beliefs and convinced many to do the same. Calling for "liberty,"17 she gathered whatever people together that listened to her and fled into the mountains away from the Catholic influence. Once they left Nalfotan, they joined their former enemies in the mountains to strengthen their numbers against the newly converted village should a war break out.

Naturally the exodus of Caquenga and her multitude of followers upset Pedro, Pagulayan, and many others of the Catholic converts. Pedro, however, was not simply going to let this woman run into the mountains and lead many others with her. Creating a plan to retrieve his lost villagers, he called upon a local from Nalfotan to go into the mountains and convince the leader of the enemy village to come to Nalfotan and talk to Pagulayan and Pedro. This leader, named Furaganan, consulted with the local of Nalfotan and decided to meet with the two other men. He ultimately concluded that he would give the Nalfotan rebels back to Pagulayan and Father Pedro in exchange for the enslavement of Caquenga. Furaganan claimed that Caquenga was a slave that formerly belonged to his mother, and he requested her return to his household. The two male parties agreed to the bargain and the rebellious Malagueg returned to Nalfotan.

While Caquenga was officially out of the picture with her enslavement, her influence did not die as quickly. The insurgents who followed her into the mountains went to the church in Nalfotan, set fire to it, and desecrated the sacred relics. In the words of the Dominican narrator of this account, "They tore the ornaments of the mass into pieces, to wear as head-cloths, or as ribbons. They tore the leaves out of the missal, and drank from the chalice, like a people without God, governed by the devil."18 One insurgent even took a sacred image of the Virgin Mary and threw his arrows at it, mocking the Christian God in doing so. The Spanish eventually put these acts down and executed the one who defiled the Virgin Mary's image as a threatening example to all others who wished to rebel and desecrate the Christian faith.

Even with the execution of the scape goat and the enslavement of Caquenga, rebellions still took place throughout the year. A number of Caquenga's followers eventually made their way to other villages, igniting more rebellions. All of these the Catholics attributed to Caquenga, "a sorceress priestess of [the devil]."19

Though infuriated and frustrated with the rising rebellions through the Upper Cagayan River Valley, the Spanish found psychological means to quell future rebellions. They utilized a powerful, influential, and willing woman to set the Catholic standard to her people. Pagulayan's sister, a member of the ruling class, chose to be baptized and took on the name Luysa Balinan. According to the account, Pagulayan and Balinan set the standard of virtuous siblings in Christ. They kept the Catholic standards honorably, influenced those around them, and gave all they had to the Catholic Churches. By 1620, Pagulayan passed away at an early age, leaving Balinan alone in the burden of sustaining Catholic motives and spreading their doctrine throughout her village.

|

|||

| Figure 3: European depiction of a Cagayan woman from the Boxer Codex. Her great quantity of gold jewelry suggest that she is a woman of upper-class, like Balinan. | |||

The Dominicans commended Balinan for her diligent efforts. They applauded her for seeking to help the poor and offering her land in a season of famine to grow food for the hungry. The account's author complimented Balinan for her knowledge of Catholic doctrine and for her openness and willingness to teach doctrinal principals to others. "She… abides in holy customs and in laudable acts of all the virtues… is consistently in the church, [and] very frequent in her confessions and communions."20 He also praised her for immediately reporting rebellions or animist practices to Catholic clergy so European authorities could repress these movements. With the help of Balinan, according to the Dominican author, Nalfotan saw 4,670 baptisms by the year 1626.

Significance of Caquenga's Revolt within Historical Context

This narrative reveals much about the culture that existed in Cagayan during the early days of proselytizing. The details recorded about Caquenga agree with the generally accepted fact that the indigenous Cagayans resisted in their conversion to Catholicism and Spanish submission. Many fought off Spanish officials and missionaries to avoid paying tribute and conversion to Christianity.21 But other aspects of perceived Cagayan and Philippine culture at the time disappear in this account.

The account shows the willingness of many Malagueg to follow Caquenga despite Pagulayan's will. Pagulayan wanted his village to convert to Christianity. Caquenga wanted them to remain in the indigenous animist religion. It shows that Caquenga, in this respect, was more powerful than Pagulayan to the Malagueg who followed her. She held enough social power to motivate the people of her village to abandon Pagulagan and join their enemy village in the mountains. According to ethnographic analyses of the precolonial Cagayan people, this was rather unbecoming of these Cagayans who were a fierce and loyal people, known for their vicious warfare and headhunting. They would raid enemy villages and collect head trophies to help promote solidarity within their own village.22 Caquenga was influential enough to convince her followers to break tradition, abandon their home land, and then join their enemies.

It is also interesting to note how Aduarte states that Caquenga and her followers called for liberty. The narrative is incredibly antagonistic towards the rebels, showing no mercy in their revolt nor their punishments. Aduarte even states that the devil led Caquenga to organize and execute the rebellion. His usage the word liberty, or "libertad" in the original Spanish, suggests that this was a theme of the rebellion and not an invention of the Catholic author.23 A detail this minor perhaps would have been omitted if the rebels did not use it frequently due to the depiction of the rebellion as being Satanic.

Not only was Caquenga and her call for liberty influential enough to convince her followers that Catholicism and Spanish domination were the enemy, she also was able to do this with Furaganan and his people in the enemy village. The people of these villages were bitter rivals. They probably waged war one with another for years, if not generations. Somehow Caquenga changed this mindset in a relatively short period of time. She convinced both Furaganan and his people to accept her followers as members of Furaganan's village. She also united these two groups of people against a common enemy: the Spanish empire and their Christianity. Although this unification was temporary and Furaganan and Pagulayan worked together to stop her revolt, the fact that Caquenga could supersede Pagulayan's authority in the first place and convince Furaganan to unite with her enemies reveals the social power she held. It is telling of Caquenga's influence in these two tribes. Her influence, however, did not end just there.

Even after her enslavement to Furaganan by the workings of Father Pedro and an unnamed man from Pagulayan's village, her influence still carried on. Her original followers destroyed the church and the sacred objects that belonged to it, carrying on the war against Christianity that Caquenga started. The execution of the Cagayan who defiled the image of the Virgin did not stop them, either. They still persisted. They went to other villages and motivated the villagers to fight against the Spanish and Catholics. Enslavement and the humiliation of Caquenga was not enough to put down the rebellion she started, neither was the execution of one of her subjects who defiled the sacred image of the Virgin. Caquenga's influence changed the Upper Cagayan Valley for the subsequent months. All of this happened in spite of the masculine influences that dominated the valley, both Catholic and indigenous.

The European Catholics struggled to gain control over the Upper Cagayan River Valley until another powerful woman began influencing the Malagueg: Balinan. While surely Balinan's example alone did not subdue the entire valley, it is interesting how much the author praised her for her efforts in expanding the Church in her village and the surrounding area. It is because she stood as a stark contrast to Caquenga. Not only was she the perfect Cagayan figure demonstrating how the people of Nalfotan should practice the new religion, she was a powerful woman. She showed the Malagueg that this new Catholic faith could be practiced diligently by a woman even though it was controlled by male priests, and the Europeans utilized her for this. In addition, European Catholics noted her social status as being a member of the ruling class, or what they called a chieftainness, and one of the wealthiest people in her village. In fact, the author wrote how the Lord prospered her "temporally" for her faithfulness.

The clergy knew what influence she had over the village and displayed her as the ideal woman. A fiercely loyal woman, Balinan reported village leaders who carried on superstitious performances to the clergy.24 She also encouraged the Malagueg to strictly learn and obey the Catholic principles.25 With her influence and wealth, she showed the Malagueg that they no longer needed to heed the animist priestesses to survive. Through her examples and teachings, the Malagueg could now rely on Catholicism because this woman, who was powerful before the Spanish advent in the river valley, remained and wealthy after faithfully following Catholic precepts.

Moreover, the fact that colonizers needed to use a woman, per this account, to gain the baptisms and respect they wanted from the Malagueg shows that the Spanish knew very well the social power women held in Prehispanic society. They experienced it first hand with Caquenga and learned that they needed influential women to follow them in order to win the hearts of the indigenous populations.

This account shows, contrary to current themes of masculine political dominance, that a woman superseded the political power and influence of her male leaders and that she held social power stronger than initially thought. Still, this example of Canquenga's revolt and Spanish response is not the only historical event where precolonial and early colonial women demonstrate social power that exceled the power of their male political leaders. It is also not the only example of clergy and colonizers utilizing indigenous women to gain control.

Further Examples of Women's Influence and Spanish Utilization

As stated earlier, Prehispanic Philippine women, especially those with religious significance, exercised noteworthy influence. Indeed, many feared them. Cultural beliefs held throughout the islands during the time of colonization show that many people feared the priestesses and shaman. Sometimes the indigenous Philippine people struggled to tell if one priestess was friendly or a witch who wanted to curse and kill others. Extreme examples of this include the existence of stories of cannibalism among the animist priesthood.26 Catholics utilized this idea of the threatening nature some of these priestesses held to bolster Spanish loyalty and to diminish the power that animism had, which survived through the Spanish colonial period and still exists today.27 Prehispanic Philippine women exercised other forms of religious power, as well, that superseded masculine political importance.

Historian Maria Bernadette Abrera researched the power of the babaylan, or the animist priestesses located in the Visayan Islands south of the island of Luzon. In her studies, she discovered that a younger class of babaylan, known as binukot, wielded a significant amount of power in precolonial and early colonial Visayan history. These binukot were frequently the daughters of nobility and local traditions believed they had spiritual powers. They were veiled from society until maturation and protected at all costs. Abrera argues that these binukot had considerable social power. Fellow village dwellers defended the binukot over everything else because of the spiritual power many assumed she possessed. Specific stories indicate that the binukot possessed an amulet that had the power to save the entire village.28 The idea that a village would prioritize a woman over their male political leader says volumes about the social power women had. In fact, it could be argued that with this evidence that these women appeared more powerful than the male village leader to certain villagers.

Two accounts from the Tagalog regions near Manila also show feminine social power during colonization. Both come from Relacion de las Islas Filipinas, written by Fray Pedro Chirino, a historian of Jesuit. The purpose of the Relacion is to record the efforts of the Jesuit missionaries in the Philippines and surrounding Asian polities during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.29 The first took place in 1597 Taytay, which is in modern-day Rizal province. One Catholic priest, Father Almerique, struggled to convert the indigenous Tagalogs in the town of Taytay, many of which the Spanish relocated from the surrounding mountains. The priest caught word of a powerful animist priestess, or shaman, still residing in the mountains. He went to the mountains and discovered that this head shaman was a bayog. He subsequently convinced the bayog to relocate to Taytay and diligently worked with the animist practitioner in hopes of converting h/er to Catholicism.30 Once the bayog accepted Christianity, the Catholic priest encouraged h/er to abandon h/er feminine persona and be baptized. In cutting off h/er effeminate hair braid, the bayog proclaimed that the Christian "anito," or god, was more powerful than all of the Tagalog anitos. With the bayog's baptism and forsaking of a feminine position, five hundred Tagalogs joined the Catholic faith through the same sacrament.

This account of the bayog shows the social power and influence this effeminate person wielded. Almerique went through much work to relocate this powerful feminine figure from the mountains to Taytay to publicly convert h/er. According to the history, which would be exaggerated due to its nature of promoting the Jesuit missionary efforts, the subsequent baptism of this bayog motivated five hundred other Tagalogs to do the same. This story is a poignant example of Catholic understanding and utilization of indigenous feminine social power. Almerique knew what influence this bayog had and went through strenuous efforts just to convert this one feminine figure. In doing so, the Tagalogs of Taytay, recognizing the social power this head shaman held, followed suit and converted as well.

The other account from the Relacion occurred around the same time in a town further west of Taytay called San Juan del Monte.31 A Catholic friar, Fray Diego, discovered that some priestesses continued to practice animism in private. They did this after converting to Christianity, opposing their masculine leadership in the Catholic Church. These priestesses were not alone in their practices. They motivated other Christianized Tagalogs to continue to secretly practice the animist traditions and to go to them for various healings and ceremonies. To their misfortune, the Catholic priest discovered their secret society, destroyed the animist emblems, and publicly ridiculed and abused the priestesses.

This second account shows that these priestesses still maintained social power even after adopting Catholicism. They even motivated other Christianized Tagalogs to disobey their new Catholic and Hispanic male leaders to secretly continue their "idolatrous" practices. Diego retaliated when he discovered these ceremonies, and he used public humiliation as a way to debase these influential women. This case, coupled with Almerique's story of converting the bayog, show the Jesuit understanding and utilization of feminine social powers and methods of counteracting it. Such acts not only prove that these feminine figures possessed a great amount of social power, enough to supersede powerful masculine figures, but that these two Catholics understood this fact and manipulated it to increase their own social power among the Tagalogs. These two Jesuit cases of understanding and utilizing indigenous feminine social power are not isolated.

Throughout the colonization process, Catholic clergy successfully demonized animist priestesses throughout the archipelago and convinced thousands of Philippine peoples that these priestesses were witches. The Spanish also used public ridicule and humiliation to subdue the influences of these priestesses.32 According to Spanish sources, it proved very effective with Philippine peoples during the early colonial period. One Spanish account even tells of bringing half-naked priestesses covered in ashes and their own blood to mass to motivate people to abandon them and to convince secret priestesses to confess their sins of apostasy.33 These two ideas, the demonization of the priestesses and public ridicule, show that the Catholic clergy and the Spanish conquistadors understood the social power these early colonial women held and that they needed to fight it in order to fully appropriate their religious and social power.

European Catholics also utilized willing women like Balinan to help with conversion because of precolonial and early colonial women's social power. Catholic priests eagerly accepted indigenous Philippine women's claim to seeing the Holy Virgin Mary in various locations. Through these women and their claims to seeing the Virgin, the Church created pilgrimage sites that indigenous Philippine people visit to this day. The clergy also found devout Catholic women who helped in the conversion process and taught the younger generations Catholic precepts. Instead of focusing on suppressing the priestesses, the Spanish also utilized willing women to promote the Catholic faith throughout their colonial era in the Philippines.34

These examples, coupled with the example of Caquenga's revolt, demonstrate that precolonial and early colonial women in the Philippines held considerable social and religious power. Though it may have been more of an exception than the rule, these women's social power sometimes challenged the power of their male political leaders. These examples also show that the Catholics knew this and fought against them.

The example of Caquenga's revolt, as well as the previously mentioned examples, add additional support and insight to the religious conflicts between foreign influences and indigenous feminine religious power structures.35

Southeast Asian historian Barbara Andaya in her work The Flaming Womb, which analyzes women in early modern Southeast Asian societies, argues that themes of "relatively high status for Southeast Asian women" exist in contemporary area studies. "[Though] male-female interaction remained typically complementary," she states, "state structures and religious teachings endorsed gender inequalities."36 This work, in part, analyzes the religious changes that came to Southeast Asian women in general as foreign powers and influences replaced indigenous religious practices new religious ideas, like Catholicism, Islam, and Confucianism. Southeast Asian women, who retain this reputation of a "relatively high female status" among many scholars, lost spiritual and religious influence and autonomy with the coming of these new world religions. Foreign religious influences seized feminine social power positions of religious and spiritual influence as many indigenous women "were obviously attracted to the imported faiths and were quick to seize opportunities to enhance their reputation for piety." Nevertheless, Andaya argues that "[ancient] beliefs did not disappear, and women were still seen as privileged channels to the supernatural."37

This argument holds true to Canquenga's revolt, Balinan's acceptance of Catholicism, the Christianization of the bayog, and the revolt of the priestesses in San Juan del Monte. These feminine figures retained social power despite the presence of foreign colonizing powers and had the ability to mobilize and influence those around them, despite the figures of masculine power influencing the world around them. Balinan and the bayog also proved to hold this image of being "channels to the supernatural," motivating hundred to accept Catholicism through their public examples of piety.

Problems with Current Views on Women-Led Rebellions

Some historical works acknowledge the animist-led revolts of spiritual leaders during the Spanish colonial period, but they limit their examples to the babaylan rebellion leaders the Visaya regions of the Philippines. These rebel leaders are called the babaylan freedom fighters, which is in reference to millenarian or anti-colonial rebellions led by babaylan. Unfortunately, not much is written about them or the influence they had. In fact, most of these babaylan rebellion leaders are drowned out by male spiritual leaders that led revolts in the same region.38 Only two dominant examples stand out from the babaylan rebels in the Visayas, and both are male. One took place led by a presumably non-effeminate male priest. His uprising was quickly put down. It started another religious revolt, but the Spanish swiftly extinguished it as well.39 The other revolt took place in the 1880s, started by a man who put on women's clothing and mannerisms when he took on his priestly role. This also failed, but started the revolt of Papa Isio, a millenarian uprising that survived until the Philippine Revolution.40 While both were influential persons, they were both either dominantly masculine or only temporarily donned a feminine appearance. Neither of them were dominantly feminine themselves, which shows little about feminine social power held during early colonial history.

There also exists a theme in precolonial Philippine histories that male political leaders held more power in general than women. Often descriptions of these leaders depict the priestesses and spiritual classes as supporting the political figures and wielding less power.41 While this may be true in certain cases, the examples of Caquenga and the other powerful feminine figures prove this theory of male political superiority as not universal and, perhaps, not even the rule. This is supported by Brewer's work, which gives plenty of examples of feminine resistance to Spanish rule their social power influencing others.42

Perhaps the most commonly noted woman-led revolt is the Silang Revolt following the British occupation of Manila and Cavite. But even here, the revolt was started by a man and was continued through his wife, Gabriela Silang, after her husband's execution. It was not organized and executed by her. She only carried out the task that her husband had left behind after his death.43 In her defense, this revolt occurred in the eighteenth century, two centuries after the advent of Catholicism in the Philippines and the subsequent curtailment of Prehispanic women's power and influence. She was influential in her own right by using her influence through the systems she inherited, especially since there is no record of her wielding power as a spiritual animist figure like the babaylan rebels in the Visayas. However, the Philippine government today honors her as one of the two only woman national heroes, which is why historians pay close attention to her and her example.44 Her legacy is immortalized, but it is only one part of feminine social power in colonial Philippine history. Caquenga's revolt paints a different picture. Her revolt reveals more of the influence women did have before it was taken from them by Catholic power and conversion.

Conclusion

The history of indigenous women in the Philippines and their social power is both promising and lacking. Like any historiography, it can never be comprehensive and always needs improvement. However, the stories of women and feminine figures like Caquenga show that these feminine influences existed during early colonization efforts. It shows that the colonizing powers, to some extent, understood these influences and manipulated other aspects of feminine social power to gain more control and influence in the region.

Using the example of Caquenga's revolt, we see that she wielded significant levels of social power that superseded the decisions of Nalfotan's leader, Pagulayan. Her decision to revolt motivated the people of her village, as well as those in the surrounding villages, to follow her decision. The only person to effectively end these rebellions and motivate the people of her village to subject themselves to Catholicism was the influential upper-class woman Balinan. Through her example and efforts, per the Dominican history, she convinced hundreds to submit to Catholic and Spanish authority.

Caquenga was not alone. The bayog of Taytay and the priestesses of San Juan del Monte also demonstrated significant feminine social power. The binukot of the Visayas and the various indigenous Philippine women who claimed to have visions of the Holy Virgin Mary did as well. These feminine figures influenced villages and helped colonizing powers spread authority through the archipelago.

This study is an effort to show that feminine social power in precolonial and early Hispanic Philippine society is a dynamic field of research that continues to change. Caquenga's rebellion reveals much about the nature of feminine social power during this transformative period. Feminine social powers had the ability to supersede masculine social powers of politics and warfare, as seen with Caquenga's rebellion. This social power also had the power to supersede the colonizing power complexes introduced by Spanish colonialism and Catholicism.

Southeast Asia is an area known for high social status among women that was threatened by colonialism and the introduction of world religions. Nevertheless, studies like this show that these gendered power complexes on an indigenous, colonial, and a trans-cultural level are much more dynamic and complex than general histories can portray. Many general histories discourage rather than stimulate world historians to make deeper analysis in topics like these because of lack of experience and time in the classroom. Accounts like Caquenga's revolt show the dynamic nature of these feminine power complexes in both the Prehispanic and early colonial societies. They add diversity to the generalized accounts of the histories of gender and colonization. They also give agency to individuals who are often grouped together in large categories of people more generalized histories.

The desire in telling Caquenga's story is that it will help encourage scholars and students to look beyond the generalized histories of the world and to understand the further complexities of feminine social power and women's agency in a colonial context. Caquenga's example of feminine social power is not an isolated event, as proven through the supplemental examples shared earlier. Certainly more examples of dynamic gender and colonial relations exist outside of the Philippine-Hispanic realm. Just as the analysis of Caquenga's story reveals more complex gender and power dynamics, other analyses can do the same as well in different histories and regions of the world.

Steven James Fluckiger is a graduate student currently in his second year of his Master's Program at the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa. His area of emphasis is in sixteenth and seventeenth century religion, gender, and sexuality in the Spanish Philippines. He can be reached at steven.fluckiger@gmail.com.

1 For a more extensive explanation of the societal roles women held in the Prehispanic Philippines, see the following: Anthony Reid, A History of Southeast Asia: Critical Crossroads (Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, 2015), 97–98. Luis H. Francia, A History of the Philippines: From Indios Bravos to Filipinos (New York: The Overlook Press, 2010), 43–44. J. Neil C. Garcia, Philippine Gay Culture: Binabae to Bakla, Silahis to MSM (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2009), 151–161. William Henry Scott, Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society (Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1994), 83–86, 184–186, 239–242.

2 Garcia, Philippine Gay Culture, 157–161, Scott, Barangay, 140–144.

3 Garcia, Philippine Gay Culture, 163–164. Francia, History, 33. Scott, Barangay, 84, 185, 239, 261, 270–271.

4 Barbara Watson Andaya describes gender in the early modern Philippines and other parts of Southeast Asia as a place on the "male-female spectrum" that can change depending on a person's age, gender, or societal functions. This contradicts the rigid, binary gender structure prevalent in early modern Europe, allowing more fluidity between genders. J. Neil C. Garcia suggests that males desiring to become priestesses had to undergo some "transformation" to become effeminate. Carolyn Brewer also supports the notion of biologically male animist priests needing to take on an effeminate persona to perform animist rituals and ceremonies. While the extent of these transformations is still unknown, the need for feminine traits to perform early colonial Philippine animist ceremonies and rituals is well established. See Barbara Watson Andaya, The Flaming Womb: Repositioning Women in Early Modern Southeast Asia (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2006), 70–75, Garcia, Philippine Gay Culture, 163–164, and Carolyn Brewer, Shamanism, Catholicism, and Gender Relations in Colonial Philippines, 1521–1685 (Hants, Englant: Ashgate Publishing, 2004), 130–137.

5 The usage of the "s/he" comes from Leonard Andaya's usage in his article about a third gender in Indonesia. I use this pronoun to avoid placing twenty-first century gender identity and transgender notions onto the bayog, or effeminate biologically male animist priest. See Leonard Y. Andaya, "The Bissu: Study of a Third Gender in Indonesia" in Other Pasts: Women, Gender and History in Early Modern Southeast Asia ed. Barbara Watson Andaya (Honolulu: Center for Southeast Asian Studies at University of Hawaii at Manoa, 2000), 27–46.

6 Other ethno-linguistic groups used different terms for their equivalents of the bayog. The Visayans used the term "asog" to describe their counterpart. Scott, Barangay, 84.

7 Scott, Barangay, 239–240. Garcia, Gay Culture, 164.

8 Scott, Barangay, 239–241, and 271. Francia, History, 33.

9 Scott, Barangay, 63–66, 69–71, 143–144, 229–231.

10 Other historians to reference on this topic include Carolyn Brewer and Zeus Salazar. See Brewer, Shamanism, and Zeus Salazar, "Ang Babaylan sa Kasaysayan ng Pilipinas" in Women's Role in Philippine History: Selected Essays by University Center for Women's Studies (Quezon City: University of the Philippines, 1996), 52–72.

11 William Henry Scott, Cracks in the Parchment Curtain and Other Essays in Philippine History (New Day Publishers: Quezon City, 1982), 96–126. John Leddy Phelan, The Hispanization of the Philippines: Spanish Aims and Filipino Responses, 1565–1700 (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1967), 15–16, 24. Francia, History, pages 31–37. Salazar, "Ang Babaylan." Scott, Barangay, 84, 128–131, 185, 239, 261, 219–222, 270–271.

12 Scott, Barangay, 263–264.

13 The Boxer Codex can be accessed at "Boxer Codex," The Lilly Library Digital Collections, accessed May 2, 2017, http://www.indiana.edu/~liblilly/digital/collections/items/show/93.

14 Diego Aduarte, Historia de la Provincia del Sancto Rosario de la Ordende Predicadores en Philippinas, lapon y China… (Manila: Colegio de Sacto Thomas), 1640, 1:348–352, accessed from Biblioteca Virtual de Patrimonio Bibliografico, http://bvpb.mcu.es/es/consulta/registro.cmd?id=399061 accessed May 2, 2017. This source will be used throughout the paper.

15 The term "Malaweg" is a modern spelling of the Malaweg language, found in present-day Rizal, Cagayan, the location of a church built by Fray Pedro. See Mal Pedro G. Galende, Philippine Church Facades (Manila: San Agustin Museum, 2007), 102.; and Lawrence A. Reid, "Towards a Reconstruction of the Pronominal Systems of Proto-Cordilleran, Philippines" in South-East Asian Linguistic Studies (1979), 3:259–275.

16 Galende, Church Facades, 102; M. O'Kane, "St. Raymond of Peñafort" in The Catholic Encyclopedia (New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911), accessed May 2, 2017 from New Advent: http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/12671c.htm; Francia, History of the Philippines, 45–46.

17 The original texts states: "…y apellidando libertad se fueron a los montes." Aduarte, Historia, 1:349.

18 Aduarte, Historia, 1:350.

19 Ibid., 1:349.

20 Ibid., 1:351.

21 Felix M. Keesing, The Ethnohistory of Northern Luzon (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1962), 170–175.

22 Scott, Barangay, 267–270.

23 Aduarte, Historia, 1:349.

24 Ibid., 1:351.

25 Ibid.

26 Juan de Plasencia, "Customs of the Tagalogs" in The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898 edited by Emma Helen Blair and James Alexander Robertson (Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark Company, 1904), 7:181–183. The Philippine Islands was an extensive translation project undertaken by Blair and Robertson. Covering 55 volumes, Blair and Robertson translated hundreds of Spanish and Catholic colonial documents into English. This occurred during the early stages of the United States' colonial occupation of the Philippines, and some of their translations are subtly influenced by the biases of American occupation. The translations are also known to occasionally leave out phrases and small details. See Glòria Cano, "Evidence for the Deliberate Distortion of the Spanish Philippine Colonial Historical Record in The Philippine Islands 1493–1898" in Journal of Southeast Asian Studies (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 39(1):1–30.

Despite these flaws, they prove to be useful translations if the scholar is aware of the flaws. They prove to be valuable when the original documents cannot be ascertained. These documents are on the public domain and can be accessed at the University of Michigan Digital Library in its "The United States and its Territories" collection. See "The United States and its Territories: 1870–1925: The Age of Imperialism" in The University of Michigan Digital Library, http://quod.lib.umich.edu/p/philamer/, accessed May 2, 2017. Project Gutenberg also contains ebook transcriptions of Blair and Robertson's translations, though not all have been transcribed as of May 2, 2017. See "Project Gutenberg," www.gutenberg.org, accessed May 2, 2017. One blog has links to the UM Digital Library collections, a list of the contents of the various volumes, and a link to a list of the existing Project Gutenberg ebooks. See "ThePhilippineIslands" in Primary Sources in Philippine History, http://philhist.pbworks.com/w/page/16367055/ThePhilippineIslands, accessed May 2, 2017.

27 Herminia Q. Menez, Explorations in Philippine Folklore (Quezon City, Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1999), 86–94. Brewer, Shamanism, 101–121.

28 Maria Bernadette L. Abrera, "Seclusion and Veiling of Women, A Historical and Cultural Approach" in Philippine Social Sciences Review (Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press, 2009), 60(1): 33–52.

29 Father Pedro Chirino and S. J. Roma, Relacion de las Islas Filipinas (Rome: Estevan Paulino, 1604), 48–52, 111–112, accessed from Österreichische Nationalbibliothek-Austrian National Library, http://digital.onb.ac.at/OnbViewer/viewer.faces?doc=ABO_%2BZ166475101, accessed May 2, 2017.

30 The description of the bayog in the text uses masculine terms and pronouns throughout. However, the text describes the braid being like the braid of the Magdalene, suggesting the Europeans placing a feminine image on the bayog. Using Brewer's and Garcia's arguments that animist priesthood required some form of feminine identity (see footnote 4), I argue this biologically male animist priest is a bayog.

31 Chirino and Roma, Relacion, 56–59, 111–112.

32 Brewer, Shamanism, 83–96.

33 Luciano P. R. Santiago, To Love and to Suffer: The Development of the Religious Congregations for Women in the Spanish Philippines, 1565–1898 (Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2005), 12–19.

34 Ibid., 33–36.

35 For a more in-depth work on the struggle between foreign religious influences and indigenous religious complexes, see Brewer's Shamanism.

36 Andaya, Flaming Womb, 9.

37 Ibid., 102–103.

38 Alfred W. McCoy, "Baylan: Animist Religion and Philippine Peasant Ideology" in Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society (Cebu City: University of San Carlos Press, 1982), 10(3): 166–167.

39 Juan de Medina, Historia de la Orden de S. Agustin de Estas Islas Filipinas in The Philippine Islands, 24: 115–120.

40 For an anthropological explanation and personal history of this priest and his gender identity, named Buhawi Dios, see Donn V. Hart, "Buhawi of the Bisayas: The Revitalization Process and Legend Making in the Philippines" in Studies in Philippine Anthropology edited by Mario D. Zamora (Quezon City, Philippines: Phoenix Press, 1967), 366–396. For Buhawi's role in influencing a later revolutionary movement, see Evenlyn Tan Cullamar, Babaylanism in Negros: 1896–1907 (Quezon City, Philippines: New Day Publishers, 1986), 30–32.

41 Salazar, "Babaylan sa Kasaysayan." Scott, Barangay, 219–224.

42 Brewer, Shamanism, 141–183.

43 Francia, History, pages 86–87. Keesing, Northern Luzon, 41–42.

44 "Selection and Proclamation of National Heroes and Laws Honoring Filipino Historical Figures," Reference and Research Bureau Legislative Research Service, House of Congress, Republic of the Philippines. Melchora Aquino, the other woman honored as a Philippine National Hero, worked with the revolution in the 1890s as a nurse. See Delia Aguilar-San Juan, "Feminism and the National Liberation Struggle in the Philippines" in Women's Studies International Forum (Storrs, CT: University of Connecticut, 1992), 5(3): 256.