America's Civil War in the Pacific: Effects of the CSS Shenandoah Incident at Pohnpei Island

Justin Vance, Anita Manning, and Jacob Otwell

On April 1, 1865, the Confederate raider CSS Shenandoah [hereafter Shenandoah] captured and sank three U.S. flagged ships and one ship flying the flag of the Kingdom of Hawaii at the island of Pohnpei in Madolenihmw, Pohnahtik Bay. 1 The incident or "battle" at Pohnpei2 brought American Civil War hostilities directly to the Pacific and during the next several months made a profound and lasting impact on those living and working in Hawaii and the Pacific Islands.

The amount of literature on the commerce raider Shenandoah has grown extensively in the past dozen years. There are now many works varying in scope and quality that recap its remarkable voyage around the world, its officers and crew, and its capture of 38 vessels, mostly US flagged whalers in the Pacific, in an asymmetric Confederate strategy that attempted to turn the tide of the war. Two of the authors of this study have previously identified how the Shenandoah and the Civil War was instrumental in bringing a virtual end to the Pacific whaling industry. 3However, there is not yet a study dedicated to closely examining the actions which took place at Pohnpei Island during its cruise. The destruction of the four whaling ships at that small Micronesian island was a critical event that led to the tactical success of the rest of the Shenandoah's cruise.

More importantly, the "battle" of Pohnpei had serious and lasting economic, legal, and social effects on Hawaii and the Pacific. Utilizing documents from archives located in Hawaii not used previously in the study of the Shenandoah's cruise, this paper investigates this action and its short and long-term effects, local and global. It analyzes the event's repercussions from many perspectives in addition to that of the belligerents including the indigenous people of the island, missionaries located on the island, and the Hawaiian Monarchy who launched a rescue mission. Using diplomatic correspondence, evidence generated by law suits, and records of a 19th Century U. S. Senate Hearing, this study also investigates the sinking of Harvest, a Hawaii-flagged and owned whaler and its owners' post-war decades long legal battles seeking reparations.

The Pacific Whaling Industry at the Start of the American Civil War

In the antebellum period, whale oil was an important part of the United States economy, one of the country's largest industries. Whale oil fueled lamps and lubricated machines among other uses. New England whalers shifted their voyages to the Pacific by the 1820s as Atlantic whales became scarce and continued until the 1870s. Over several decades the whaling grounds expanded off the coast of Chile to the far western Pacific, off the coast of Kamtchatka to the Okhostsk Sea, and finally northward into the Bering Sea and the Arctic. From 1820, Hawaii was the American whaling fleet's main Pacific port. Whaling was big business in the Pacific and the primary economic driver of the Hawaiian Islands.

Hawaii's geographic location made it the best place for refitting the many ships as journeys grew longer (up to five years) as whales became scarcer. Captains used the Hawaiian ports twice a year to refit their vessels, "to unload their cargoes and ship them back east, stock up on supplies and hire thousands of Hawaiians, called Kanakas, as crew members."4 Between the 1820s and 1860s there were eight different years that the number of ships arriving in Hawaiian ports numbered more than five hundred. Kuykendall reports "the number of American vessels engaged in the business" and "the quantity of whale products brought into American ports" was greatest in the 1840's (1846—736 ships and 1845—16,000,000 gallons) "but the total value of such products was greater in the 1850s (1854—$10,800,000) because whale oil and whalebone prices were higher."5 Honolulu and Lahaina were the main ports with fewer ships stopping at Hilo and Kealakekua, Hawaii Island, and Waimea and Koloa, Kauai. Hawaii Historian Gavin Daws writes:

It became commonplace to say that no one could do business in the islands without the whalers. The wages of native seamen, profits on the sale of supplies, commissions on the transshipment of oil and bone from the islands to the United States, speculation in bills of exchange, and returns on all sorts of services from ship chandlering to boardinghouse keeping made whaling indispensable.

The Pacific Whaling Industry and Confederate Naval Strategy

The destruction of the North's whaling industry was part of the naval strategy developed by Confederate States Naval Secretary, Stephen Russell Mallory, and Confederate Naval Agent in Europe, Captain James Bulloch. By destroying the great New England Pacific whaling fleet, they expected to damage the North's economy and thus hinder their war effort. To that end, Bulloch issued orders to Shenandoah's Captain:

Sir: You are about to proceed upon a cruise in the far-distant Pacific, into the seas and among the islands frequented by the great American whaling fleet, a source of abundant wealth to our enemies and a nursery for their seamen. It is hoped that you may be able to greatly damage and disperse that fleet, even if you do not succeed in utterly destroying it.

— Detailed Instructions from Commander Bulloch, C.S. Navy,

to Lieutenant J.I. Waddell, C.S. Navy, October 5, 1864.6

Though the endeavor would not make a difference in the outcome of the war, it would prove to play a significant role in the demise of Hawaii's whaling industry.

The Shenandoah was built in England and launched in 1863 as the Sea King. The CSS Shenandoah was 230 feet long, had a thirty-two foot beam, carried three rigged masts and was equipped with steam power. Sleek and swift, she could make sixteen knots under sail and nine knots with her 150-horsepower engines.7 Armaments included two 32-pound and two 12-pound cannon, both rifled for accuracy, deadly against virtually unarmed whalers. Her Captain was James I. Waddell, formerly a U.S. Navy Lieutenant with over twenty years' experience. In late 1864, the Shenandoah set out on its mission.

The American Civil War comes to Pohnpei

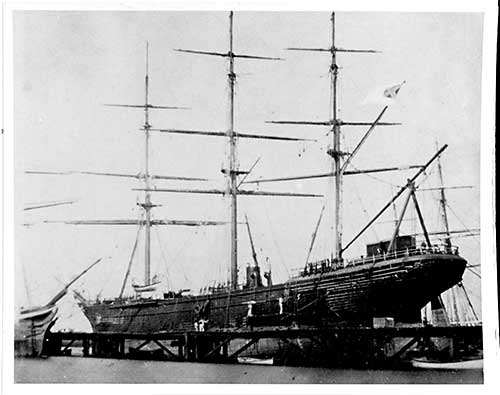

On January 25, 1865, the Shenandoah reached Melbourne, Australia, by Cape of Good Hope and the Indian Ocean taking 10 Union ships enroute. It was dry docked and refitted in Melbourne, where the only known photograph of the Shenandoah was taken.8 The Shenandoah, its crew, and officers were treated like rock stars in Melbourne, where its visit is still of interest.9 Despite the efforts, "officially anyway," of the Governor of Victoria to discourage recruiting, the Shenandoah left Melbourne on February 18 in search of the Pacific whaling fleet with 42 much needed newly enlisted crewmembers.10

On March 30, 1865, the Shenandoah came across the Hawaii-based trading schooner Pfiel on the open seas and learned of the presence of American whalers at Pohnpei in the Caroline Islands, known then as Ascension.11 As they closed their distance the Shenandoah fired a warning shot. In response the Pfeil ran up the colors of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Waddell believed the Pfeil was deceiving him and sent over a boarding party to investigate. The officer in charge was satisfied that the ship was as she claimed, a Hawaiian vessel, in the area for a trading exploration. Still, the boarding party used deception and confusion to get the information they wanted from its captain. The boarding party lied, saying they were an American cruiser, the Miami, and it worked.12 Pfeil's Dutch captain informed Waddell there were no ships at nearby Strong Island which the Pfeil recently visited. However, three weeks earlier he had seen three Union whaling vessels in or around the Ascension Islands.

Even though the Pfeil's Captain informed Waddell there were no ships in the Strong Islands he insisted on seeing for himself. The Shenandoah set sail and arrived at the most easterly of the Caroline Islands, a favored stopover for equatorial whale ships.13 Not finding anything in the Strong Islands, Waddell set course for Pohnpei to investigate the reports gathered the previous day.

Under full sail and steam, Shenandoah raced to Pohnpei and April 1, 1865, caught four whalers in port at Pohnahtik, Madolenihmw. As morning turned to afternoon the Shenandoah arrived at the harbor mouth. Coming along side in a small boat, Harbormaster Thomas Harrocke offered his assistance to guide the Shenandoah into the Harbor. Harrocke, a former British subject and according to Waddell's memoirs an escaped convict from Australia,14 had been living on Pohnpei for nearly ten years and had assimilated into the culture. He had married a Pohnpei woman, had tattoos and markings similar to the island men, and was a known middle man for tribal chiefs when trading and negotiating with English and American sailors.15 Waddell was in a foreign harbor and knew nothing of what laid beneath his keel, nor how narrow the entrance really was, so he accepted Harrocke's offer. Waddell recalled that "the harbor was most too confining for a vessel of the Shenandoah's length, and there were a few unknown dangers below the surface of the water."16 Waddell instructed Harrocke to direct the Shenandoah to lie inside the harbor reef cutting off all harbor access. Not all officers were keen on having someone else on their vessel: second-in-command Lieutenant Conway Whittle offered that "if he got us aground, death would be his instant portion."17 The Shenandoah was flying the common flag of Britain (the Union Jack) as it entered the harbor (it was April Fool's Day!). Harrocke assumed that they were English surveyors or on a similar mission. Within minutes the Shenandoah was safely anchored and could show their true colors and begin to take the four vessels as prizes.

Waddell ordered four small boats to be lowered. In each he placed two officers with a hand full of armed crew members, essentially part of the Confederate Marine force. The four boarding party officers were Lieutenant Grimball, Lieutenant Lee, Lieutenant Chew and Lieutenant Scales. These men were in charge of bringing the captains, mates and the papers of registry back to Waddell for interrogation and imprisonment.

As the boats lowered into the water and the Union Jack was replaced by the Second National Flag of the Confederacy, a mystified Harrocke asked "what flag that was?" A deck officer told Harrocke "those four ships are prizes to the Confederate Government." Harrocke replied, "you and the Yankees must settle that business to suit yourselves. If I had known what you were up to, maybe I should not have piloted you in, for I don't like to see bonfire made of a good ship."18

Of the four ships under investigation three flew a United States flag: the Edward Cary of San Francisco, the Hector of New Bedford and the Pearl of New London. The fourth ship, the Harvest of Honolulu flew the flag of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Within minutes after dispatching the boats the officers of the four boarding parties had returned with their prizes' respective mates and papers "but the masters were absent."19 The four vessel's captains had gone ashore to visit some of the American missionaries living on the island.20 Whittle recalled this event with tremendous pride:

Oh what an April fool to the poor Yanks. There were no Captains onboard as they were at the lee harbor 'on a bust.' The boats shoved off, we fired a gun & ran up our flag. What a time.21

Waddell kept men at the ready to intercept the captains and their parties once they returned around sunset. Captain Thompson of the Hector, Captain Chase of the Pearl, Captain Baker of the Edward Carey, and Captain Eldridge of the Harvest were eventually brought on board as well. Waddell began to question the captains about where they made home port. The Captains of the Hector, the Pearl and the Edward Carey gave up their respective information because they knew they were American ships; therefore, they cooperated with Waddell because there was really nothing they could do. It will be later demonstrated that Captain Eldridge of the Harvest explained that his ship was Hawaiian owned and should be spared. Harvest flew a Hawaiian flag, was owned by the Honolulu firm H. Hackfeld & Co., and was manned by Hawaiian seamen.22 In 1865, Hawaii was an independent Kingdom, long recognized by world powers such as Britain, France, and the United States. In 1858, even before the war, records show that there were forty-five Hawaiian registered vessels, thirteen of which were whalers.23 On August 26, 1861, the Kingdom had declared neutrality in the American Civil War:

Be it known to all whom it may concern, that we, Kamehameha IV, King of the Hawaiian Islands, having been officially notified that hostilities are now unhappily pending between the government of the United States and certain States thereof styling themselves "The Confederate States of America," hereby proclaim our neutrality between said contending parties. That our neutrality is to be respected to the full extent of our jurisdiction, and that all captures and seizures made within the same are unlawful, and in violation of our rights as a sovereign. And be it further known that we hereby strictly prohibit all our subjects, and all who reside or may be within our jurisdiction, from engaging, either directly or indirectly, in privateering against the shipping or commerce of either of the contending parties, or of rendering any aid to such enterprises whatever; and all persons so offending will he liable to the penalties imposed by the laws of nations, as well as by the laws of said States, and they will in no wise obtain any protection from us as against any penal consequences which they may incur. Be it further known that no adjudication of prizes will be entertained within our jurisdiction, nor will the sale of goods or other property belonging to prizes be allowed. Be it further known that the rights of asylum are not extended to the privateers or their prizes of either of the contending parties, excepting only in cases of distress or of compulsory delay by stress of weather or dangers, of the sea, or in such cases as may be regulated by treaty stipulation. Given at our marine residence of Kailua this 26th day of August, A. D. 1861, and the seventh of our reign.24

Some of Waddell's officers thought Harvest's claim legitimate, but "Waddell, noticing some technical irregularities in the transfer, declared the Harvest forfeit."25 In his journal, Waddell justified the taking of the Harvest by claiming,

She bore the name Harvest of New Bedford, carried an American register, was in charge of the same master who had commanded her on former whaling voyage, and her mates were American. I therefore confiscated her and held her master a prisoner.26

In similar fashion, second-in-command Whittle stated the Harvest:

was the only one about which there was any doubt, but she had no bill of sale, a Yankee Captain & mates…she, with the rest, was condemned as a prize. The mates were all put in irons.27

Records show that some of these statements are false. The masters of the Harvest before and after its 1862 sale and re-registry as Hawaiian are completely different, 28 and the taking of the Harvest will be explored further below. Regardless, all four ships were stripped of value and burned over the next ten days including the Harvest.29 Among the booty from the Harvest were 300 barrels of whale oil from its recent Western Pacific cruise.30Whittle rejoiced in the action of the men that afternoon:

Having the Capts., 1st & 2nd Mates onboard, and not knowing the feeling of the natives we withdrew our men, after having taken out all navigating instruments. And we all had a great rejoicing. This amply repays us for our monotony and is not a bad haul, as the cargo alone of one, i.e. 300 gallons of oil is worth $40,000. These raise our prize list to 11 & two bonded, making 13.31

But the most important item taken off of the vessels were charts showing locations used by the entire Pacific whaling fleet, retrieved from the Edward. Waddell recalled in his memoirs "I not only held a key to the navigation of all the Pacific Islands, the Okhotsk and Bering Seas, and the Arctic Ocean, but the most probable localities for finding the great Arctic whaling fleet of New England, without a tiresome search."32

Another piece of irony from that April Fool's Day presented itself in Harvest crewmember George S. Rowland. Rowland had served in the Union Navy earlier in the war and must have thought he left America's Civil War far behind. Now, thousands of miles away in South Pacific, he found himself the victim and prisoner of the Confederate States of America. Rowland stayed in Honolulu after the war working in the Harbor Master's office and died February 25, 1867.33

The Shenandoah was short on crew from the beginning of its cruise, so when it captured ships, their crews faced the option of being marooned, put in the brig, crammed on a bonded34 ship, or joining the Shenandoah crew. In this case, seven men chose to join the Confederate Navy.35 On April 11, 1865, the remaining prisoners were ordered to sign a "parole" and set ashore the island of Pohnpei. Just two days later, April 13, 1865, having taken on all the plunder from its four prizes and fresh provisions from the islanders it could carry and with refreshed crew who had enjoyed generous liberty time,36 the Shenandoah set sail to hunt down the American Pacific whaling fleet. She left 120 sailors marooned on the island. The impact of these future operations and the marooned crews were to have lasting effects on the indigenous population of Pohnpei and for the Kingdom of Hawaii. However, before considering them, it is worth considering the legal wrangling that surrounded the seizure of the Harvest, which persisted over 30 years, involved the U. S. Senate, the governments of Spain and England and tested, rather than resolved, the issue of neutrality of shipping in wartime.

The Case of the Harvest

Why did Waddell take the Harvest, a Hawaiian flagged ship, as a prize? On several occasions prior to this engagement Waddell and the Shenandoah encountered several ships from various nations, including the Pfeil, which was a Hawaiian vessel. The most commonly repeated and largely accepted side of the story in the now many books about the Shenandoah come from Captain Waddell's account. But there are also the accounts of the crew, mates, and captain of the Harvest. According to their sworn testimony, they were ordered to lower the flag of their registered nation (which the Confederate officer referred to as a dish-rag), produced registry paperwork documenting the 1862 transfer to ownership in the Hawaiian Kingdom, and the phrase Harvest of Honolulu written across the stern.

Waddell's decision supposedly rests on the Harvest being unable to provide a bill of sale proving a non-United States registry. In his memoirs he stated,

...the party returned, was captured, and conducted to the Shenandoah. The masters of the three vessels which had shown the American flag could give no good reason why their vessels should not be confiscated and themselves held prisoners, and the master of the vessel which flew the Oahu flag could not produce a bill of sale, nor could he swear to the sale of the vessel.

As noted above, Waddell continued, "she bore the name of Harvest of New Bedford, carried an American register, was in charge of the same master who had commanded her on former whaling voyages, and her mates were American. I therefore confiscated her and held her master as a prisoner."37

It is evident that Waddell understood and respected the idea of neutrality. He had proven this several times during the voyage. Waddell realized that Pohnpei was ruled by several chiefs, and that he needed to address this matter with the high chief of this area. In his memoirs he stated "the question of confiscation being settled, and the masters taken care of, it became important to sound his Majesty on the subject of neutrality, and therefore he, with his council, made us a special visit to talk the subject over."38

Also in evidence are the memoirs of Waddell's second-in-command, Conway Whittle. He gave a similar account of what happened that day in that he asserts that there was no question that the Hector, Pearl, and the Edward Carey were all United States registered vessels. Regarding the Harvest, he only states that Lieutenant Grimball, leading the Harvest boarding party, could not find evidence that persuaded him that this was not a US vessel. Whittle explains that when the four captains came back from the island to their ships they were immediately captured and taken to the Shenandoah,

when they learned what we were they [the four captains] were astounded. They were all put in irons except the Capt. of the Harvest, his deposition was taken, and the sale of the vessel was, as she had the same Capt. & Mates, all Yankees, the same name, and no bill of sale, considered bogus, and was put in limbo with the rest.39

Waddell and Whittle felt that there was no evidence stating that the Harvest was not an American vessel, therefore the Harvest was condemned.

However, the testimony of Captain Eldridge and his crew has seldom been heard and analyzed by historians. Their testimony is found in the published letters and documents of a hearing by the U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Affairs in 1894 pertaining to the claim of owners, officers and crew of the ship Harvest captured by the Shenandoah: Hackfeld and Company asked to be heard as they wanted to recoup their losses. The Senate Committee's investigation of the happenings at Pohnpei and its proceedings appear to provide an unbiased and accurate account of that day, if almost thirty years after the event. No new conclusions came from these hearings. Nonetheless, the transcripts of the Senate hearing are valuable to historians for its record of the testimony of several officers and crew who served on the Harvest.

The Senate hearing sought to resolve two major questions. The first was to ascertain, even if the Harvest and its owners were of Hawaii, were reparations due to the American citizens that served aboard her for their losses? On whalers, officers and crew were compensated by receiving a portion of the "catch of oil" a voyage. For example, Captain Eldridge was to receive a 1/20 share of the profit. The United States government has an obligation to protect its American citizens and their property. To that end the hearing attempted to determine whether the United States was able to offer such protection in a time of war and if not, as the parties of the Harvest's lawyers argued, it should reimburse them due to the actions of a faction of the rebellious government of America. The parties of the Harvest's lawyers, argued:

...that Captain Eldridge and his associate officers of the Harvest were American citizens; that they had done nothing inconsistent with their character, relations and duties as such; that they were fully entitled to the protection of their Government against the outrage to which they were subjected and that they are entitled to the consideration due to those who have suffered wrongs against which it was the duty of their Government, but which for the time being it had not the power to protect them.40

Second, the Committee sought to determine did the Harvest's owners, as non-American citizens, deserve reparations from the US Government based on Waddell acting as a misfit towards the Harvest knowingly committing a crime against a neutral power or if he acted in a correct manner under the circumstances? The following are answers in a line of questions asked of Charles Hamitl, first mate of the Harvest, regarding the events of that day that appear today to resolve that question. Charles Hamitl was born in Providence, Rhode Island, December 21, 1844. He claimed he was a native-born United States citizen and was "never naturalized in any other country; I at all times during the period embraced between the 13th day of April, 1861 and the 9th day of April, 1865, both inclusive, bore the allegiance to the United States."41 It is significant that Hamitl had served on the Harvest since November 1862, when it was registered out of New Bedford, Connecticut. Additionally, Hamitl knew the Pacific Ocean. He had sailed many cruises from Honolulu, Hawaii, throughout the Pacific to the Arctic, looking to gain fortune in whaling.

Another question the Senate Committee was trying to sort out was how much cargo the Harvest could carry. That would determine how much the vessel could earn. The most impressive numbers from October 1863: sperm oi1—150 barrels, bow-head oil—1,500 barrels, and whale bone—30,000 pounds. The following period showed similar hauls. These allowed Mr. Hamitl to send $200 in gold to his mother [$5425 in 2016].42 By 1864 Hamitl was ready to return home with Captain Loveland, who had served as the Harvest's master before Captain Eldridge. Instead, Loveland convinced Hamitl to stay behind and serve as the Harvest first mate to increase his earnings.

On December 24, 1864, the Harvest set out on what was to be her final voyage. Hamitl, promoted to first mate, was arguably then the most experienced whaler on the Harvest. At end of March 1865 the Harvest arrived in the Ascension Islands.43 Hamitl explains it was not uncommon for whalers to stop over at other ports or islands to resupply. Once Hamitl and the Harvest arrived in Pohnpei, they met the American whaling vessels Pearl, Hector and Edward Cary. They too where resupplying their vessels with wood, water and more before they sailed to the Arctic whaling grounds. According to Hamitl, on April 1, 1865

...some of the crew reported a steamer [the Shenandoah] in sight; Captain Eldridge had started about 9 A.M. in company with the other three captains, to visit Mr. Sturgis [sic], American missionary, that lived at Roanakiti Harbor, some twelve miles from where we [the Harvest] were anchored; I took [Mr. Hamitl] his [Captain Eldridge] spy-glass and looked at the stranger and called her a Russian corvette; ordered the steward to set the flag, not telling him which flag to set, continuing at my work, being anxious to get the decks cleared up by night . . .44

Once Hamitl gave the order to set the flag the crew promptly and more importantly set the Flag of the Kingdom of Hawaii.45 It was about four o'clock that afternoon when the Shenandoah moored roughly a quarter mile off the four whaling ships that were sitting in the harbor and virtually blockaded the harbor entrance and exit.

Mr. Hamitl continued his Senate deposition:

Mr. Rollins, second officer, called me on the deck and told me that the steamer had set no colors and that she was lowering boats, and he called my attention to the officer's uniforms on the forecastle: he [Mr. Rollins] had served in the Union army before joining us at Honolulu; the uniform which the officers wore, he said, was a Confederate uniform; in a few minutes the boat ran alongside of us with two officers and the crew, all armed; as soon as the officers came on deck the steamer ran up the Confederate flag and fired a gun; the fifth lieutenant—I believe his name was Slidell—as he came on deck, asked to see the captain; I told him he was absent down the coast, visiting the American missionary, but would be back soon; he then ordered me to produce the ship's papers; I asked him what steamer that was, and he answered: "The Confederate steamer Shenandoah Captain Waddell; last port, Melbourne Australia."46

The six other crew members that also gave testimony for the 1894 hearing also recalled that Lieutenant Slidell's attitude towards the Harvest was one of complete and utter disrespect. The names and jobs of the men of the Harvest who gave testimony regarding this were Native Hawaiians: Tom Smith, fourth officer; Angustus Paul, boat-steerer; Mauna, boat-steerer; Kekipi, boat-steerer; John Vahine, boat-steerer and cook; Hikian, who was a naturalized Hawaiian citizen. It should be noted that out of 37 crew members exclusive of the captain, the fourth officer and 28 seamen were Hawaiians by birth47 Their testimony provides a rare glimpse into the voices of the non-elite classes of the time.48 They stated,

the steamer [Shenandoah] sent a boat and crew to each vessel, and hoisted a strange flag. The person in command of the boat that boarded us, took the first and second officers of the bark Harvest as prisoners in his boat, and ordered us to haul down the 'dish-rag' (meaning thereby the Hawaiian flag), which we declined doing. The person in command of the steamer's boat then commanded the first officer of the Harvest to order us to haul down our flag.49

Then, and only then, after the Hawaiian flag was taken down, did Slidell place a guard from the Shenandoah on board and Slidell ordered Mr. Hamitl to recover the ship's papers. Mr. Hamitl went into "the captain's trunk, and delivered them to the officer; he looked over the papers, and put them all back into the tin case on the captain's table, and told me to take the papers, and go with the second officer."50 After producing the Harvest's papers Slidell ordered both Mr. Hamitl and Mr. Rollins to report to Captain Waddell aboard the Shenandoah. Back aboard the Shenandoah Waddell inquired as to Captain Eldridge. Again Mr. Hamitl stated that he was on shore visiting the American missionary who lived nearby. Waddell detained Mr. Hamitl and Mr. Rollins until Captain Eldridge arrived. In addition, Waddell detained the officers of the other three whaling vessels until their captains arrived. 51

In November 1865, the Harvest's owners had begun official protest against those responsible for destroying their vessel. They provided proof that an officer from the Shenandoah ordered the Harvest to take down their Hawaiian flag among ignoring other indications that she was a Hawaiian vessel;

Harvest had become before sailing on her voyage as hereinafter set forth, the true and lawful property of these [appellants], and had likewise complied with all the laws necessary to invest her with the character of a Hawaiian vessel, and did sail from this port of Honolulu with a Hawaiian Register, with the words 'Harvest of Honolulu,' legibly and plainly painted on her stern, and with the Hawaiian flag and none other, and with almost the whole of her crew, other than the captain and three of the mates, aboriginal Hawaiians, on the 24th day of December, 1864.52

Mr. Hamitl continued his testimony by relating how Waddell sent an "armed boat to intercept the captain when he arrived at the entrance of the harbor, and somewhere about dark of the same night he [Captain Eldridge] was taken up by that boat and brought directly to the Shenandoah."53 Once Eldridge was on board Waddell asked him to take an "oath that the Harvest was not an American ship."54

It is here that Hamitl's testimony becomes most interesting. As he did hear the full conversation between Captains Waddell and Eldridge, Hamitl creditably stated that Captain Eldridge "refused to [take the oath] but told him [Waddell] that he was an American citizen, belonging to Massachusetts and his officers also were American citizens."55 It is possible that this conversation may have been misinterpreted as this deposition was not taken until decades after the incident. Or, maybe, it is the truth, and Captain Eldridge misunderstood what Waddell truly asked him, which may have been to ascertain the nationality of the ship.

Very few accounts from Captain Eldridge exist today. However, a single letter dated September 25, 1865, written by Eldridge to the owners of the Harvest details the amount of the catch acquired during the short Hawaii to Pohnpei voyage. It also offers an account of the equipment that was taken from the four vessels during the April 1 attack. Eldridge states "I arrived here on the 26th of March, with 350 barrels sperm oil, all well on board . . . on the 30th, the rebel Shenandoah came in, and immediately made all the masters prisoners, taking all our charts, chronometers, all navigating instruments."56 More important, the letter relates Eldridge's version of the series of questions he was asked by Waddell. Eldridge wrote "I was taken in the cabin and sworn, when, as near as I can recollect, the following questions…'Where were you born?' My answer—'At sea.' 'Where were you brought up?' 'In Massachusetts.' 'Can You swear that this vessel was legally sold to a foreign owner?' 'I believe it to be so.' Where are your transfer papers?' 'In Honolulu; I have not got them with me; but here is the Hawaiian register.'"57 The following is a transcribed copy of the Hawaiian registry that Captain Eldridge had with him and would have presented to Captain Waddell.

CERTIFICATE OF HAWAIIAN REGISTRY

Know all men by these presents, that pursuant of the Hawaiian Islands, the "Harvest" of Three Hundred and Fifty-Two and 24/95 tons, whereof Henry Hackfeld, a denizen, Frank Molteno and James I Dowsett, subject, are equal and only owners, and being ship rigged, carrying three masts having two decks measuring One Hundred and Five Feet in length , Twenty-Seven Feet Six Inches in breadth of beam, and Fourteen Feet Nine inches in depth of hold; built at Middleton Conn., A.D. 1825, late the Harvest, under the flag of the United States, has been duly registered at the Custom House in Honolulu as a Hawaiian vessel, and is therefore entitled all the rights and privileges appertaining to Hawaiian vessels, whether in the ports of the Kingdom or of other nations, or upon the high seas.

In witness whereof I have hereunto set my hand and official seal at Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands, this First Day of December, A. D. 1862—Signed W. Goodale, Collector General of Customs.58

Eldridge continued, "he [Waddell] said 'That will do; this game has been played long enough; I shall confiscate your ship. Put this man in irons.' (Which they did) and I never went on board the Harvest again."59

The letter's last paragraph helps explain how the finding of charts and other information on that day led to the Shenandoah's successful mission in the following months, as they destroyed much of the Union whaling fleet. Captain Eldridge directly accused Mr. Hamitl and three others in cooperating with Waddell by informing them where to find them (the rest of the whaling fleet). Eldridge concludes his letter;

Mr. Hamitl, Mr. Rowland, Mr. Coit and cooper raised on a whaleboat and left here about the first of August for Guam; I doubt their reaching there. All three of them were rank secessionists. They were left free on board the man-of-war, and treated me like a dog. Mr. Hamitl gave them all the information where to find the Arctic fleet—took my charts and showed them the whaling track. After we were put ashore I never had much communication with them.60

The Harvest was the last vessel burned since it took some time for the Shenandoah to bring over all the cargo and whatever else she wished to take from the Harvest. Waddell had ordered Hamitl on board the Harvest to show his men where the whale oil was stowed and where the bread, flour, beef and pork was kept. While Hamitl was waiting around, he had a conversation with Waddell who explained to him why "the vessel was a 'bona-fide' American ship, asking me [Mr. Hamitl] to look over the stern and see the American eagle, and that among the papers he found no bill of sale." Waddell also said that "he thought it was a shame for a young man like me [Mr. Hamitl] to be serving on board of a whaler, and I told him that I would rather serve on board of a whaler than go to sea with a crew of Englishmen such as had got around him and under the Confederate flag."61 Waddell told Hamitl why he felt it was his duty to destroy the American Whaling fleet in the Pacific,

that the United States was ravaging the Shenandoah Valley, and that he was doing what he could on the sea to pay them up; that he knew all about the Harvest; that she had the United States flag flying when he boarded her, and that she was as much an American ship as the other ships found at the Ascension Islands. That he had examined the matter fully and assumed the responsibility; he said he knew what he was about and a precedent of what he was doing.62

Regardless of whether Waddell acted appropriately there is no doubt the Harvest was a vessel appropriately flagged by a neutral power.

The International Quest for Reparations for Harvest

Just two days after learning their ship had been destroyed, members of H. Hackfeld and Company began to work through the Hawaiian government to receive reparations. August 12, 1865, Hackfeld wrote to His Excellency R. C. Wyllie, Hawaiian Minister of Foreign Affairs,

…the mail which arrived this morning from San Francisco, we have received intelligence from Messrs. J. C. and Co., of that place, informing us that the Hawaiian bark Harvest, commanded by Captain Eldridge, manned principally with a crew of Hawaiian Seamen, and having on board 300 Barrels of Sperm Oil, was burned in the month of April 1865, whilst riding at anchor near the Ascension Islands, by the so-called Confederate Steamer Shenandoah, under the command of Captain James E. Waddell.63

Hackfeld Company continued in their letter to Mr. Wyllie;

owners of the said Hawaiian bark Harvest, who are Hawaiian Subjects, and on behalf of all whom it may concern, we take this first occasion to note this our protest against the action of the commander of the so-called Confederate Steamer Shenandoah, or whomsoever he may represent, in violation in an unlawful manner the property of Hawaiian Subjects; claiming the right to extend the same at any future time and place, and claiming as indemnity the sum of Seventy-Five Thousand Dollars with interest thereon from the time of destruction of the said bark Harvest, her outfit and cargo, and invoking through Your Excellency the assistance and protection of His Hawaiian Majesty's Government by claiming this indemnity.64

This letter began a decades long process seeking reparations for Shenandoah's destruction of the Harvest.

The first major intervention in this case between the Hawaiian Kingdom and a foreign body was at war's end when Hackfeld learned the Shenandoah was being surrendered to the British Government. Following that surrender, it was handed over to the American Government for auction. March 22, 1866, Manley Hopkins, Hawaiian Consul-General at Liverpool, wrote to United States Consulate at Liverpool:

on the part of Mr. Hackfeld, a Hawaiian subject by denization, [an act of the crown by which a foreigner becomes their subject and is granted certain rights including the ability to own land. The obsolete status is akin to Permanent Resident today] now residing at Bremen, and his partners, Hawaiian subjects residing in Honolulu, joint owners of the late whaling bark Harvest, I beg to bring to your notice that in April, 1865 whilst the said barque Harvest, under Hawaiian Colors and entirely Hawaiian owned, was peacefully pursuing her avocation . . .and on the first of the said month April, the Harvest was boarded by the cruiser or steamer Shenandoah. The person in charge of the steamer imprisoned Captain Eldridge and the officers of the Harvest, putting them in irons…afterwards plundered the Harvest of provisions, stores, chronometers, sails and 50 barrels of sperm oil; and having made the crew leave the vessel, the person in charge of the Shenandoah cut the bark Harvest adrift and set her on fire, whereby she was burnt, destroyed, and totally lost to her owners, with her cargo, outfit, appurtenances and incidents. The above facts are declared upon oath by part of the crew of the Harvest, who arrived in Honolulu in November 1865, in the bark Kamehameha V, which vessel was dispatched by the Hawaiian Government to fetch the crew from the said Island of Ascension.65

Also in his letter Mr. Hopkins confronted the United States Consulate and Government for taking possession of the Shenandoah and the sale of the vessel and stated "I, His Hawaiian Majesty's Consul-General, in behalf and at the instance of the said owners of the late bark Harvest, demands to participate in the net proceeds of the steamer Shenandoah, her appurtenances and incidents in respect of the sum of 75,000 dollars, the value of the bark Harvest and her cargo of sperm oil & etc., destroyed by said cruiser or steamer."66 Hopkins concludes;

I beg, in conclusion, to remind you that when the wanton outrage on the Hawaiian Flag, and the willful and unwarranted destruction of the Hawaiian property took place, the Hawaiian Government was neutral and friendly to all the United States of America, and had not made any acknowledgment of the seceding States as a separate or belligerent power, and had issued a Circular to all Governments of their (the Hawaiian) neutrality and determination to take no part in the pending hostilities.67

This said, it was now up to the United States government to settle this claim and determine if the U. S. should take responsibility for what happened on Pohnpei.

Thomas Dudley, United States Consul at Liverpool, having no authority to make a ruling on Hackfeld claims, sent it to Secretary of State William H. Seward. Mr. Dudley forwarded Secretary Seward's response to Mr. Hopkins and Mr. Hackfeld:

Mr. Hopkins does not state the grounds of the claim made by him. It is not to be supposed that he conceives that Government of the United States to be directly responsible for outrage committed outside their jurisdiction by a cruiser armed in hostility to them upon the property of neutrals. Nor can this Government admit that when the offending cruiser was surrendered to it by Great Britain it was taken subject to any liens, actual or potential, whether voluntary created by rebels or such a party injured by her marine torts might conceive himself authorized to invoke the establishment of, in the Courts of a neutral power, for the reparation of his damages.68

Simply, Seward said the United States was not responsible for the conduct of those representing the rebellious Confederate States of America government. The most devastating part of his response was "the answer to this must be that the Executive Department has no discretionary power in respect to the disposition of the proceeds of rebel property. The exclusive right to appropriate them is vested in Congress."69 To receive compensation, the Harvest's owners had to take their claims to the U.S. Government legislative branch. The Foreign Affairs Committee heard the case but at the hearing's conclusion gave the Harvest's owners no reparations.

Seward did, however, state in the same letter that the two chronometers taken from the Harvest should be "restored, if found among the stores of the Shenandoah."70 However, a letter from a lawyer representing the Harvest from the 1894 proceedings shows that even this tangible and identifiable property was not returned:

although the Secretary of State caused all personal effects and property identified as belonging to the Harvest and her officers and crew found on the Shenandoah to be delivered to the owners thereof, the proceeds of the sale remain in the treasury.

Though the Harvest's owners did not receive any financial relief based on this concession by Seward, it does demonstrate that he understood and was convinced that the Harvest was truly a Hawaiian flagged and registered vessel.

Mr. Hackfeld also filed a private lawsuit against the Harvest's insurance company in Europe when the underwriters too refused to take any responsibility. The suit was successful, and Harvest was awarded a small sum by the court. Apparently, though the insurance would not have covered an act of war between nations, it did offer some benefit in the case of piracy which is what the court decided happened to the Harvest. In response to this decision Mr. Hackfeld wrote Hawaii's Minister of Foreign Affairs:

in a lawsuit carried on by our agents against the Insurance Companies with whom the bark Harvest had been insured, judgment has been rendered by the Court of Bremen in favor of the owners of the vessel, and against the underwriters, on the grounds that the steamer Shenandoah was a pirate, never having been in a port of the so-called Confederate States of America, and the latter, moreover, possessing no rights, sanctioned by international law, to issue letters of mark.71

This said, he continued to encourage the Hawaiian Kingdom to assist in recuperating reparations for the Harvest;

having succeeded in recovering a smaller portion of the loss sustained by the burning of the Harvest, and learning from the public papers that negotiations with regard to the settlement of claims for similarly destroyed property are progressing between the United States of America and Great Britain, we most respectfully take this opportunity to request that His Majesty's Government will further keep alive our just claim against the parties who are responsible for the piratical acts committed by the steamer Shenandoah alias Sea King.72

The Hawaiian government gladly assisted with all requests from Hackfeld and Company, did so for another 30 years. However, all fell on deaf ears and no payouts were ever given. Although the United States received $15.5 million dollars from Great Britain for damages caused by the Confederate commerce raiders in 1872 to help satisfy the numerous claims from direct damages to US flagged merchant ships,73 the owners of the Harvest never received from the United States government any of the $75,000 for its losses caused by the Shenandoah.

The evidence is overwhelming that the Harvest was legitimately a vessel of a neutral country. If Waddell did not believe the evidence supporting this, there are two possible motivations for him to look skeptically at the evidence.

One is there were many transfers of vessels to neutral flags in "form only" happening during the Civil War. Hoping for protection from Confederate Raiders, a number of ships frequenting the Pacific changed their registry to the Kingdom of Hawaii to fly a neutral flag. One documented example was the Arctic by Messrs. C. Brewer & Co. In mid-1863, Brewer, with offices in Honolulu and Boston approached Albert F. Judd, a Hawaii citizen then a Harvard law student. Judd related the plan to his father:

I am to be a "ship owner." Mr. Lunt has written to know if I would not "own" the 'Arctic' for the house of C. Brewer & Co. who are transferring all of their ships to Hawaiian owners for fear of their being taken by the J. Davis pirates. They sell me the bark, I give them my note for the amt. & charter them the bark for 20 years . . .

Judd's letter details what accountants term a 'sale lease back.' He is the owner on paper, but invests no money. Control is returned to C. Brewer & Co. and Judd is paid $100 for his trouble, and makes a friend in the Honolulu business community where he will soon be a lawyer searching for clients.74 Brewer filed the paperwork with the Hawaiian Consul in Boston and the bark was registered No. 50, new series. 75 After signing in September 1863, Judd began to take an interest in his 'acquisition,' chatting with the sailors in Hawaiian as the vessel loaded, shadowing in a chase boat as the Arctic left Boston

... with her Hawaiian colors floating at the Mast Head ... May favorable winds waft her speedily to her destined Haven & no pirate dare lay hands upon her. A great deal is being said as to whether Semmes would respect the Haw'n flag. I say he will ... if he touches any ship but an American, he at once changes his character from that of a regular belligerent to that of a pirate ... His character has too much of uncertainty about it now, to allow him to take such a questionable step as the seizure of the Arctic, though he be satisfied that her legal owner is an Hawaiian but her beneficial owner an American.76

For the Arctic, carrying general merchandise, the Hawaiian flag provided protection; for the Harvest, carrying whale oil, it did not.

The strongest reason Waddell may have ignored credible evidence is if he had burned the three American whalers and let the Hawaiian one go it could have warned the rest of the whaling fleet. When Waddell let the Pfiel go, he had done it without revealing his ship's true identity. If this was why he found the Harvest an American ship despite the evidence, he covered it well in his memoirs and the official record, but his motivation would have been clear as knowingly taking a ship of a neutral country would make him what many have suggested even taking only U.S. flagged ships: a pirate.

Looking at the evidence, it does not seem that Waddell's claims that the ship had the same master and no bill of sale warranted the capture of the Harvest. It did not have the same master, though one of the mates, Hamitl, was the same as before its 1862 transfer. Also, it is not required under customary international law for a ship to carry its bill of sale; it is required they carry their registry, which was presented to Waddell. "Harvest of Honolulu" was painted across the stern of the ship. Though it cannot be proven, it appears that Waddell was looking for reasons that he could declare the Harvest a U.S. owned ship likely for reasons of military necessity—preventing enemy knowledge of his operations. Whatever one's interpretation, one must feel for the men and owners of the Harvest. Their ship and cargo destroyed because they were thought to be American and then were not awarded reparations because they were not American.

Effects on the Peoples of Pohnpei

The local inhabitants of Pohnpei were a clan-based society led by five major chiefs. Even before the Edward Cary, Hector, Pearl and Harvest arrived in Pohnpei the indigenous population were affected by foreign commerce and interaction with outsiders. Foreign ships began frequenting Pohnpei in the 1830s as with other parts of the Caroline, Gilbert, and Marshall Islands visited by American whalers.77 Additionally, missionaries arrived from the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM), headquartered in Boston, Massachusetts. In the 1830s and 1840s, the ABCFM set up a good foundation for a Pacific outreach through their efforts in Hawaii.

In 1852, the first wave of ABCFM missionaries arrived in Pohnpei. With the constant arrival of American whaling ships, policing the morality of the local population and whalers was a constant up-hill battle for the missionaries, who described the 1860s as a decade of complete lawlessness.78

Arguably, the most damaging event of that time period was the Shenandoah's April 1, 1865, attack. Captain Waddell took care to treat the local king (the Nahnmwarki of Madolenihmw) with respect and not break any of the local laws in the capture and confiscation of what he explained to the King as the property of his enemy. On the eve of the departure of the Shenandoah, Captain Waddell told the King he would "tell our President of the kind hospitality he had shown to the officers of the Shenandoah and the respect he had paid our flag." The King responded, according to Waddell,

tell Jeff Davis he is my brother and a big warrior; that (we are) very poor, but that our tribes are friends. If he will send your steamer for me, I will visit him in his country. I send these two chickens to Jeff Davis (the chickens were dead) and some coconuts which he will find good.79

The crew also received ample shore leave during the Shenandoah's thirteen days at the island and were also accommodated very well. The actions on the water ended and the Shenandoah set the four ships on fire. The chiefs sent men out to salvage what they could. The vessels did not sink completely, leaving them stranded on the harbor reef. In trying to keep the peace, the missionaries decided to completely burn the ships so that it did not encourage further fighting and thievery amongst the local population. Most disruptive, however, was that the Shenandoah stranded 120 sailors on the Pohnpei shore from the four prizes captured. Those stranded included New Englanders, Pacific Islanders, and Hawaiians, the latter constituting the vast majority. This had a damaging effect by upsetting Pohnpei's internal politics. The American Civil War now brought consequences to the far side of the world.

Once the 120 sailors made it to shore, groups of them were placed under different clan chiefs for care by the King (Nahnmwarki of the Madolenihmw).80 This upset a lower but rival chief, the Wasai of the Madolenihmw who was angry the clans he oversaw were not included in the division of the men and the spoils that came with them. This resulted in internal raids and clashes in which many of the sailors took part that just fell short of all-out war. The master of the Edward Cary even helped lead the forces of the Nahnmwarki. Eventually, missionaries on the island were able to calm the feud. Still, for the next four months, between the Shenandoah's departure and arrival of the rescue vessel Kamehameha V from Hawaii, the missionaries remembered the time after "the Confederate ship's departure as one of chaos and drunken revelry."81 It was described as the drunkest time in Pohnpei to date. The number of firearms on the island also increased. An American Missionary, Mr. Sturges, feared this event would affect the entire island population. It also forced the population to help the stranded men.

The effect on Pohnpei was profound. It was a formative event in island history, etched in the collective island memory. Though nearly 150 years have passed, the impact is still evident on Pohnpei from the Shenandoah's attack. In the same letter Captain Eldridge wrote Mr. Dowsett describing the happenings of that fateful day, he described his future plans: "…I have been trying to get a little money ahead, but can't; when I get back I always find myself in debt…as to my means of living, I shall go to piloting—it don't take much to live here."82 Eldridge did stay on Pohnpei for the remainder of his life. His descendants are living on the island today, as are those of the other crew members who remained in Pohnpei. Pohnpei islanders are familiar with the incident as are Eldridge's island descendants.83

Escape to Guam

Some of the men stranded on Pohnpei did not sit waiting to be picked up by the next passing ship. Others had no idea what to do next. After bringing all those to be stranded to dry land the same Englishman, Harrocke, who guided the Shenandoah into the bay, took the last surviving whale boat84 and the rest of the officers of the Shenandoah back to their ship. They set sail and pointed north in route to destroy the Arctic whaling fleet. As a gift for his assistance Captain Waddell gave Harrocke the whale boat. Hamitl, First Mate of the Harvest, insisted that the whale boat belonged to him. He wanted it and after much debate Hamitl got the boat.85 Hamitl realized that he needed to let the world know that the "pirate ship" Shenandoah was about to destroy the entire Arctic whaling fleet.86 To get the word out he knew he needed to reach Guam. There, hopefully he could find a ride back to Honolulu to inform the Hawaiian government what happened to the Harvest.87

Hamitl, along with Second Officer Rollins, Third Officer Coit and a cooper (coopers were skilled in ship building and repair), John Leary, went searching for volunteers to help sail to Guam. It was not easy to recruit. The journey from Pohnpei to Guam would be difficult, nearly 850 miles through the middle of the Pacific Ocean during the height of typhoon season in a makeshift rigged whaling boat. Hamitl recalled:

We tried to get volunteers to start for Guam as she was [the whaling boat] but it was impossible to find anybody willing to risk the voyage without the boat being lengthened and decked over, so we concluded to deck her over and lengthened her six feet, which we did; and somewhere in the later part of July, 1865, we started for Guam.88

While they were fitting their whaling boat for the dangerous voyage, American Missionary Sturges encouraged them to sail for Guam. He hoped if this endeavor succeeded the remaining whalers would depart sooner. Hamitl saw the benefit in having a certified letter from Mr. Sturges as it would go a long way in explaining what happened to them. The letter was available for the late July departure. The newly crafted whale boat left with just the four officers and cooper onboard. The sail from Pohnpei to Guam was uneventful. Barely a month later they arrived in Guam August 4th or 5th, 1865.

Upon their arrival Hamitl met with Don Philipi de La

Cortes, Governor of Guam. Guam, a Spanish

colony, remained neutral during the Civil War. In his meeting with the Governor, Hamitl told him of "the circumstances of the capture and destruction of the Harvest and the other three ships at Ascension Islands by the Shenandoah... the

Governor told me [Hamitl] that [as] the Harvest was an American Ship and

that we were American citizens he would furnish us with suitable clothing and

board until such time as he could send us home to the United States.89

Between Hamitl being an American citizen and Mr. Sturges' letter it seems that the Governor of Guam concluded the Harvest was an American vessel, but this must be taken in context as at this point Hamitl's number one priority was likely his safety and rescue of the other seamen. The Governor needed to decide whether or not to intervene on the Harvest and ultimately took a non-judgmental approach. The four crew members that arrived on Guam were treated as they were, Americans.

The Governor sent a Spanish ship to Pohnpei to see if they could be of assistance. However, by the time it arrived, the Kamehameha V had already rescued the sailors. Shortly after, the governor arranged transportation for Rollings, Coit and Leary back to San Francisco. Mr. Hamitl stayed on Guam, waiting for the next whaling vessel to arrive. It finally came April 1866, nearly a year after the Shenandoah incident. Hamitl sailed for another Arctic whaling season and, in November 1866, arrived back in San Francisco.90 Hamitl's whaling boat was sold by the governor for 300 dollars in gold coin and the proceeds turned over to the US Government which resulted in another unsuccessful claim by Hamitl to receive compensation.91

Rescue Mission by Hawaii

By August 1865, word had arrived in Hawaii of the events at Pohnpei. The Pacific Commercial Advertiser reported on August 12, 1865:

the arrivals of the American clipper ship Reynard and the American whaling bark Joseph Maxwell from the Arctic Ocean on Thursday morning, brought us intelligence of the destruction of fourteen whale ships by the pirate Shenandoah and of the probable of destruction of a larger portion of the Arctic and Ochotsk fleets…in our issue of June 24th, we gave the statement of the Captain of the Hawaiian schooner the Pfeil, who reported having been spoken by a strange vessel near the Ascension, and being boarded by officers who reported the stranger as the British ship Miami. We then gave it as our opinion that it was the Shenandoah, and by the news received it has proved too true. Upon leaving the Pfeil she [Shenandoah] squared away for the Ascension and there burned four vessels and left their officers and crew on the island…the Harvest was also owned in this city [Honolulu] by Messrs. Pfluger Dowestt and Molteno, neither of whom are Americans and the vessel was also under the Hawaiian flag. We were told the Harvest, was insured in Europe.92

The Hawaiian Government decided to send the bark Kamehameha V to the Ascension Islands to bring back the Hawaiian crewmen left there by the Shenandoah. When the Kamehameha V departed Pohnpei a few dozen men elected to stay, including Eldridge, the Harvest captain, with the results related above. The Kamehameha V arrived in Honolulu with "98 officers and men" from the Edward Cary, Hector, Pearl, and Harvest November 18, 1865.93

The End of the Shenandoah's Operations and the spawning of the end of the Pacific Whaling Industry and the rise of the Plantation era in Hawaiian History

The Shenandoah left Pohnpei with the whalers' charts and plans in hand. On May 27, 1865, after capturing the whaler Abagail, its 2nd mate Thomas Manning joined the Confederate Navy along with 10 Native Hawaiians from the crew.94 With these and the other advantages already possessed by the Shenandoah, the ship captured another 24 vessels (23 of them whalers) in June 1865 in the Bering Sea and Bering Straits. All but four were burned. The remaining four were placed in bond with the idea of collecting ransom, loaded with prisoners, and directed to San Francisco. Waddell learned of Lee's surrender at Appomattox, but as he also learned of the Danville Proclamation from his encounters with other ships that May, he continued to fight. However, on August 2, 1865, when the Shenandoah met the HMS Barracouta in the eastern Pacific, its captain convinced him the war was over. Waddell, with input from officers and crew, decided to head around Cape Horn and return to England versus making for Australia or South Africa. Captain Waddell surrendered the ship to British forces in Liverpool, England, November 6, the last Confederate command to surrender. Interestingly, nine of the ten Hawaiians serving onboard the ship signed a petition in favor of supporting Waddell's ultimate decision to continue on to England.95 It is worth noting that Hawaiians were included on the petition because rarely, if ever, could people of color at this time vote or be witnesses in court. The impact of the Shenandoah on Hawaiians extended far beyond this singular case of Hawaiian civil liberties.

The Shenandoah's depredations accounted for much of an industry-wide "60 per cent drop in numbers of whale ships afloat occurred between 1860 and 1866."96 Around 50 whaling vessels were captured, mostly by the CSS Shenandoah and CSS Alabama. This raiding also led to the sale of many more Northern whale ships to foreign owners for fear that they would be captured flying under American flags.97 To add to all this disruption, near the beginning of the war, forty-five ships from the American whaling fleet were purchased by the United States Government for war use. All but five were sunk at the entrance to Charleston Harbor in an effort to block the port. Sixteen are recorded as sunk in the main channel and twenty in Maffitt's Channel.98 "Holes were drilled, then plugged, in the vessels' hulls, and their holds filled with New England granite." They were then sailed to the harbor's mouth and the plugs were pulled scuttling the vessels.99 By all accounts, this "Stone Fleet" was ineffectual as a blockade, but added to the woes caused by the war for whaling. The American Civil War thus played a significant role in the demise of whaling, ultimately bringing a sharp, and what proved to be an irreversible depression to an industry that had begun a slow decline, but otherwise may have endured decades longer despite the increasing scarcity of whales and birth of the petroleum industry in 1859. The blow to the whaling industry both in New England and Hawaii helped contribute to the economic transition that was occurring in the Kingdom of Hawaii as its main industry shifted from whaling to sugar plantations.100 The war provided a stimulus for Hawaii's sugar industry as Southern grown sugar was no longer available to the markets of the Northern states. Hawaii's total sugar exports rose from 1,444,271 pounds (722 tons) in 1860 to 17,729,161 pounds (8,864.5 tons) in 1866101 —an average growth rate of total exports of 175.36% per year between those years.

Conclusion

The American Civil War coming to Pohnpei had serious and lasting effects on Pohnpei, the Pacific, and Hawaii. There the Shenandoah captured four whaling ships and gained valuable intelligence that led to many more prizes. One of the ships, the Harvest, was destroyed illegally as it belonged to subjects of a nation that had officially declared neutrality and the incident resulted in decades of legal action between three nations (England, US, and Hawaii) and private courts that never resulted in any compensation for the owners from the British or US governments. Perhaps more fascinating are the repercussions at Pohnpei from many perspectives including the seamen, mates, and captains on both sides, the disruption in missionary operation, and on the native who still remember the episode as a formative event in their history. And of course, the Hawaiian Monarchy who funded the rescue mission to save the marooned whalers and whose economy was completely decimated in the short term and transformed by the sharp decline of whaling and the rise of sugar agriculture in the long term.

Dr. Justin Vance is Chair of the Department of Culture, History, and Politics at the College of Western Idaho. He is the author of many publications and presentations on the American Civil War's effects on the Hawaii and Pacific region as well as World War II in the Pacific. Formally of Hawaii, he was the winner of the 2015 Hawaii History Educator of the Year Award. justinvance@cwidaho.cc

Anita Manning is an Associate in Cultural Studies, Bishop Museum, Honolulu, who has assisted students and teachers with a History Day research guide and has judged for more than 20 years. She is the author of several publications on the history of science in Hawaii and articles on the history of Honolulu Elks Lodge 616. She may be contacted at manninga001@hawaii.rr.com

Jacob Otwell works to better the community as the Membership Engagement Supervisor at the West Seattle YMCA. He earned a BA in History from the University of Hawaii-Hilo where he received the History Department Outstanding Writer of the Year Award for 2009 and also holds an MA in Diplomacy and Military Studies from Hawaii Pacific University. jacob_otwell@yahoo.com

1 Pohnpei is largest island in what is now the Federated States of Micronesia. Madolenihmw is a land division giving its name to a large offshore area. Pohnahtik is the smaller bay area where the burning took place. See Suzanne Finney and Michael Graves, Site Identification and Documentation of a Civil War Shipwreck Thought to be Sunk by the C.S.S. Shenandoah in April 1865, (Washington, DC, American Battlefield Protection Program, National Park Service, 2002), 5–6, 15,18–19.

2 Should the phrase "Battle of Pohnpei" be used to describe the action that took place? There was only one military force, however, there were clearly two opposing sides and although one chose not to resist, the potential was there as the whalers did carry some weapons and outnumbered the Confederate forces in manpower. A great deal of destruction did occur. Additionally, in 2000 maritime archaeologists received a National Park Service American Battlefield Protection Program grant to survey the wrecks of the four sunken ships so the site met the U.S. Government definition of a battlefield. See Finney and Graves. 2002. However, the action was one sided as the whalers did not resist so although this was a military action, "battle" may not be the best description of events.

3 Justin W. Vance and Anita Manning, "The Effects of the American Civil War on Hawaii and the Pacific World," World History Connected, vol. 9 no. 3, 2012 http://worldhistoryconnected.press.illinois.edu/9.3/vance.html

Justin W. Vance and Anita Manning, "Pacific Islanders and the Civil War," in Asians and Pacific Islanders and the Civil War, National Park Service, Washington DC, 2015.

4 Eric Jay Dolin. Leviathan: The History of Whaling in America. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2007, 245.

5 Ralph S. Kuykendall, The Hawaiian Kingdom, vol. II, 1854–1874: Twenty Critical Years, (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1953), 35.

6 U.S. Naval War Records Office, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion. Series I vol. 3: The Operation of the Cruisers, 1 April 1864–30 December 1865, (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1896), 749.

7 Murray Morgan, Confederate Raider in the North Pacific: The Saga of the C.S.S. Shenandoah, 1864–1865, Pullman: Washington State University Press, 1995, 15.

8 US Naval History and Heritage Command photo # NH 85964 https://www.history.navy.mil/our-collections/photography/numerical-list-of-nhhc-series/nh-series/NH-85000/NH-85964.html

9 On the 150th Anniversary of its visit one author of this article was invited to offer a keynote speech on the C. S. Shenandoah in the Pacific for the American Civil War Round Table of "The Effects of the Shenandoah on Hawaii and the Pacific World," American Civil War Round Table of Australia, Melbourne, Australia, February 14, 2015).

10 Terry Smyth, Australians Confederates, How 42 Australians Joined the Revel Cause and Fired the Last Shot in the American Civil War, Sydney NSW, Ebury Press, 2015.

11 "A Suspicious Vessel," Pacific Commercial Advertiser, 24 June 1865, 2.

12 Murray Morgan, 164.

13 Tom Chaffin. Sea of Gray: The Around the World Odyssey of the Confederate Raider Shenandoah. Hill and Wang. 2006, 189.

14 James I. Waddell and James D Horan. C.S.S. Shenandoah: The Memoirs of Lieutenant Commanding James I. Waddell. Bluejacket Books. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 1996, 144.

15 Chaffin, 190–93.

16 Waddell, 144.

17 William C. Whittle, The Voyage of the CSS Shenandoah: A Memorable Cruise. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2014, 136.

18 Cornelius E. Hunt. The Shenandoah; or the Last Confederate Cruiser. London: C.W. Carleton & Co., 1867, 126–127.

19 Waddell, 148

20 Chaffin, 193.

21 Whittle, 138.

22 See Committee on Foreign Relations, United States Senate, "Letters and Documents Relating to the Claim of the Owners, Officers, and crew of the Ship Harvest captured by the Shenandoah, 1 August 1894" for witness affidavits. 1894 testimony indicated it sometimes flew an American flag when convenient.

23 Kuykendall, 4.

24 "Proclamation," The Polynesian, 14 September 1861, 3. For a full discussion of the neutrality decision by the Kingdom see Vance and Manning, "The Effects of the American Civil War on Hawaii and the Pacific World."

25 Murray Morgan, 170.

26 Waddell, 148.

27 Whittle, 136–137.

28 Agreement, made between the Owners of the bark "Harvest" and John P. Eldridge. FO&Ex-24 1865, Hawaii State Archives. Also, "The Northern Whaling Fleet," Polynesian 6 Dec 1862, 3; "Marine Journal," "Arrivals," "Departures" The Friend, 1860–1865.

29 Chaffin, 209.

30 "The Raid of the Shenandoah," Hawaiian Gazette, 12 August 1865, 69.

31 Whittle, 137.

32 Waddell, 145.

33 The Friend, March 1867, 24. Also, United Veterans' Service Council, "Record of Deceased Veterans," Card file M 477, Hawaii State Archives, Honolulu, HI.

34 "Bonded" refers to a legally binding (in theory) promise from a captured vessel for future payment in exchange for the safety and release of the vessel. The Shenandoah bonded 6 of its 38 prizes usually when it had no place to maroon prisoners or no more space for them. In cases where it captured multiple ships at the same time, it placed the crews of multiple ships on a single bonded ship destroying the rest.

35 Shipping Articles of the Shenandoah. Six crewmembers from the Hector and one crewmember of the Pearl enlisted. Four were born in Portugal, two born in America, and one born in Peru. These men are not to be confused with the ten Hawaiian men that enlisted discussed later in this article.

36 Chaffin, 205.

37 Waddell, 148.

38 Waddell, 148–49.

39 Whittle, 137.

40 Letters and Documents Relating to the Claim of the Owners, Officers and Crew of the Ship "Harvest" captured by the "Shenandoah," Heard by the Senate Committee on Foreign Affairs on August 1, 1894. 9.

41 Letters and Documents, 19.

42 Letters and Documents, 19–20.

43 Today known as Pohnpei.

44 Letters and Documents, 21.

45 Letters and Documents, 38.

46 Letters and Documents, 21–22.

47 Letters and Documents, 37.

48 More documentation of the high percentage of Native Hawaiians in crewing whaling vessels and the Civil War can be found in the Hawaiian language newspaper Ka Nupepa Kuokoa which on April 22 and 29, 1876, printed lists of names of Hawaiian crewmembers who had served on prizes captured by the Shenandoah.

49 Letters and Documents, 37–38.

50 Letters and Documents, 22.

51 Ibid.

52 Public Instrument of Protest of November of 1865, 7, FO&Ex-24 1865, Hawaii State Archives, 7.

53Letters and Documents, 22.

54 Letters and Documents, 23.

55 Ibid.

56 Public Instrument, 7.

57 Public Instrument, 8.

58 Public Instrument, 5.

59 Ibid.

60 Ibid.

61 Letters and Documents, 24.

62 Ibid.

63 Letter H. Hackfeld and Company to Hawaiian Minister of Foreign Affairs, August 10, 1865. FO&Ex-24 1865. Hawaii State Archives.

64 Ibid.

65 Public Instrument, 16.

66 Ibid.

67 Public Instrument, 16–17.

68 Public Instrument, 17.

69 Ibid.

70 Public Instrument .18.

71 Ibid.

72 Ibid.

73 "The Alabama Claims, 1862–1872," US Department of State, Office of the Historian. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1861-1865/alabama Retrieved. August 22, 2017.

74 Albert F. Judd to Gerrit P. Judd, 25 August 1863, Judd Collection, MS Group 70 Box 27.7.31, Bishop Museum.

75 "Owners and crew of the Hawaiian Bark Arctic," Reports of Committees of the House of Representatives for the Second Session of the 53rd Congress (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1894), Report 430, 4–5.

76 Albert F. Judd to Lizzie [Elizabeth Judd Wilder], 18 October 1863, MS Group 70 Box 71.3.18, Bishop Museum.

77 Hanlon, David. Upon a Stone Altar: A History of the Island of Pohnpei to 1890. University of Hawaii Press. Honolulu. 1988.

78 Hanlon, 124.

79 Waddell, 153–154.

80 Hanlon, 124.

81 Ibid.

82 Public Instrument, 8.

83 John Sigrah, Interview by Justin W. Vance. Honolulu, HI, July 10, 2009.

84 Whale boats were either stored on board or towed behind the whaling vessels. These were the boats that went out to the whales, killed the whales, and used to bring back their catch to the main whaling vessel for processing.

85 Letters and Documents, 28.

86 Letters and Documents, 26.

87 Ibid.

88 Ibid.

89 Letters and Documents, 27.

90 Letters and Documents, 28.

91 Letters and Documents, 10

92 The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. (Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands), 12 Aug. 1865.

93 "Ship Manifest March 18,1861–Nov. 15, 1865" MFL 73 Box No. 4 (1009967). Hawaii State Archives.

94 Shipping Articles of the Shenandoah. Also, it should be noted that in David Chappell and Kevin Reilly's. Double Ghosts: Oceanian Voyagers on Euroamerican Ships. Florence: Taylor and Francis, 2016, p. 93, it is stated that "thirteen Kanakas, mostly Hawaiians had to join the Confederate navy when the raider Shenandoah sank four New England whalers in Pohnpei harbor." That assertion seems incorrect based on available documentation. No Hawaiians enlisted on the Shenandoah off the four prizes taken at Pohnpei. The 10 Hawaiians that did enlist did so off the whaler Abagail on May 27, 1865. There is also no evidence that they "had" to as hundreds of others Kanakas from captured prizes did not enlist. Other evidence that suggests they were not coerced is that four of the ten Hawaiian enlisted at the pay rate of full Seaman at $29.10 per month versus a rate of $19.40 for Ordinary Seaman, $18.00 for Marine Private, or $16.00 for Landsman all lower ranks which others on board held including some Whites (Shipping Articles of the Shenandoah). However, until more evidence is located we cannot know for sure the circumstances or motivations of the Hawaiians who joined.

95 U.S. Naval War Records Office, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion. Series I vol. 3: The Operation of the Cruisers, 1 April 1864–30 December 1865, (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1896), 783.

96 Theodore Morgan, Hawaii: A Century of Economic Change, 1778–1876, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1948, 143.

97 George W. Dalzell. The Flight From the Flag: The Continuing Effect of the Civil War upon the American Carrying Trade. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1940.

98 Sidney Withington, The Sinking of the Two "Stone Fleets" During the Civil War, Marine Historical Association Publication no. 34, (Mystic, CT: Marine Historical Association, 1958), 62.

99 MacKinnon Simpson and Robert B. Goodman, Whale Song: The Story of Hawaii and the Whales, Honolulu: Beyond Words Publishing Co., 1989, 107.

100 Vance and Manning, "The Effects of the American Civil War on Hawaii and the Pacific World."

101 Kuykendall, 141.