FORUM:

Organizing World History

"Innocuous" Organizing Devices for World History

Rick Szostak

"Only a centralized organization of issues and viewpoints, of material and interpretations, can hope to meet the constructive requirements of the writing of world history."1

The study of world history reflects a keen desire among not only historians but also governments and their citizens to bring some comprehensive understanding to the entire sweep of human history. Yet instructors and students often bemoan the difficulty of achieving coherence: of drawing meaningful connections across discussions of Persians and Aztecs and Polynesians.2 The danger, of course, is that in our desire to bring order to world history we become superficial: We seize on some organizing principle – some meta-narrative – and ignore everything that does not fit. This paper asks, then, if we can achieve greater coherence in world history by employing organizing devices that are innocuous in two important respects:

· They do not force us to simplify world history in order to comply with some meta-narrative.

· They do not interrupt narrative flow as we discuss individual events or processes in world history

We want, that is, to achieve greater coherence in world history without sacrificing the complexity inherent in the subject matter.

This paper will first outline four different types of innocuous organizing devices, and then discuss some implications of their use.

Flowcharts

World history texts have increasingly taken a thematic focus in recent decades, following polity and culture and economy through time. One important lesson that might be imparted by courses in world history involves the importance of cross-thematic interactions in human history. Though interdisciplinarity is widely applauded within the contemporary academy, that academy is nevertheless organized around powerful disciplines. Students may well come to imagine that political scientists, cultural anthropologists, and economists study largely independent realms of human activity. The world historian knows, however, that polity and culture and economy – and demography, health, technology, science, social structure, psychology, and physical environment – interact in important ways in history. Indeed, one can usually detect influences from several of these themes in any major event or process in human history.

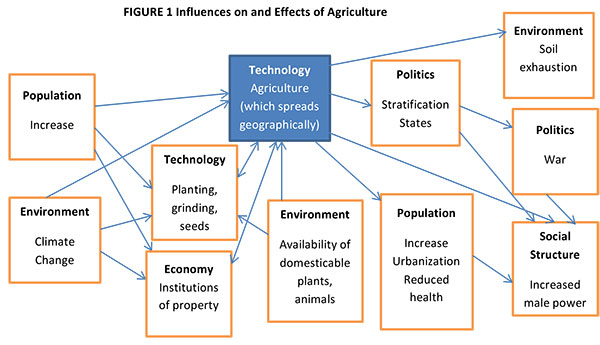

This important lesson can be communicated powerfully through the use of flowcharts. Figure 1, for example, captures some of the main influences on and effects of the development of agriculture.

Students, of course, need to be warned that such flowcharts necessarily simplify a complex historical narrative. They need to be told, that is, that such diagrams are a complement to the textual discussion rather than a substitute for this. (The sort of student that may be tempted to just "look at the pictures" may nevertheless still learn more than they would have done in the absence of such diagrams.) With that caveat in mind, a student can quickly grasp from such a diagram that this particular historical transformation involved interactions among several distinct themes. If a world history text contained dozens of such diagrams, this important lesson of complex thematic interactions would be communicated powerfully.

It is also worth noting here that students have different learning styles. Some students learn best from reading and are readily able to recall complex narratives. Other students are more visual in their learning styles. These students will especially benefit from the use of flowcharts. They will use the flowchart to help them keep track of the details of the narrative. They might even come to draw their own diagrams for events or processes for which these are not provided in the text – and could be encouraged to do so from time to time in the questions at the end of chapters.

To this point, our flowcharts have aided students in organizing their understandings of particular historical episodes. But a series of flowcharts can also aid students in drawing connections across historical episodes. Note that "states" and "war" and "gender stratification" are among the effects of the development of agriculture in Figure 1. Later figures in a world history text can then capture the (other influences on as well as the) effects of states or war or gender stratification. Since each individual flowchart communicates the importance of cross-thematic interactions, a series of such flowcharts guides the student to appreciate world history as a cumulative set of such interactions. This is surely one of the key lessons that we hope to impart in world history: that the events and processes of one time period build upon the events and processes of earlier time periods. We discuss how states emerge in one chapter and discuss myriad effects of state formation in later chapters. Students thus gain a powerful appreciation of why we address Mesopotamia and Persia and the Abbasids in one course. We might then guide them to develop their own maps of complex historical processes. Benjamin Reilly3 indeed advocates having students draw visual maps of world history as a whole.

Such flowcharts can also impart another key lesson of world history: that broadly similar processes are observed in different times and places. The text may discuss how agriculture emerged independently in several different parts of the world; Figure 1 highlights the critical fact that the emergence of agriculture reflected similar influences and had similar effects across these different times and places. The flowchart, by providing a clear indication of similarities, then allows us to appreciate differences – such as why agriculture does not generate large states in the highlands of New Guinea. Students can then understand another reason why we discuss Aztecs and Mongols and Polynesians in the same course: to first appreciate and then try to comprehend both the similarities and differences in historical processes. It deserves to be stressed that we are best able to appreciate historical uniqueness if we also appreciate historical similarity.

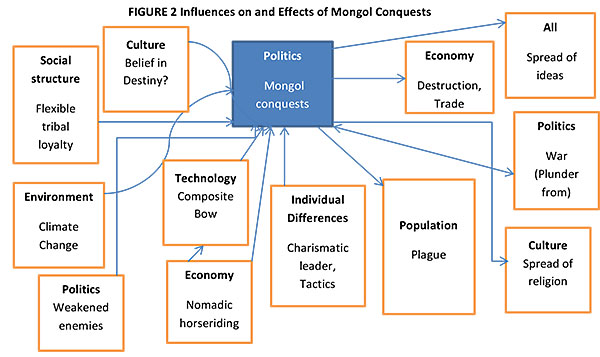

Interactions among societies always involve thematic interactions. It is ideas or objects or people that move between societies: These have an effect as they affect polity or economy or culture. And we have already learned that changes in any one of these themes will likely encourage changes in others. A traveler may carry a religion to a new land; if that religion takes hold in the new land it will likely have political repercussions. Flowcharts are thus also useful in capturing episodes of societal interaction and indicating the effects of these. Figure 2, for example, addresses the Mongol conquests. It indicates that a single episode of interaction can have diverse impacts on a variety of themes.

|

|||

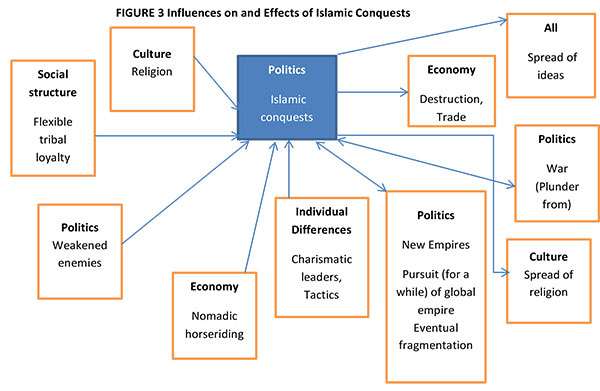

| Figure 2: Note: Students might be asked to explore similarities and differences between this diagram and a similar diagram regarding the earlier Islamic conquests (see Appendix). The "belief in destiny" refers to a hypothesized sense that the Mongols were destined to rule the world. | |||

Common Challenges

The lesson regarding the similarities and differences in historical processes across time and place can be communicated further by explicitly discussing the challenges faced by different types of historical actors. Farmers need to worry (among other things) about their harvested crops or livestock being stolen. Rulers need to worry about bureaucrats pursuing self-interest rather than the good of the state. Merchants need to worry about bandits, rulers, and other merchants taking advantage of them. We can identify a handful of critical challenges affecting dozens of key types of actor: builders, technological innovators, artists, scientists, explorers, priests, migrants, parents, voters, and more. Much of what we discuss in world history involves attempts to address these various challenges. States and armies and fortifications serve (in part) to protect food from theft. Trade is only feasible if merchants form networks (and often convoys) and negotiate safe passage with (generally greedy) rulers. Rulers attempt to limit the scope for bureaucratic abuse of power by variously spying on their bureaucrats, punishing disobedient bureaucrats harshly, cycling governors through different territories, and/or relying on slaves or foreigners to fill senior offices; they also encourage or develop cultural attitudes that encourage bureaucrats to value honorable service to the state. We can usefully compare the particular strategies pursued by different rulers to address this common challenge (and why they make different choices) and how well they work.4

A typical world history text will address the rise and fall of dozens of empires. When empires fall, there is often evidence of increased corruption, increased power of local governors and/or landowners, and difficulty in raising enough in taxes to finance the necessary army and bureaucracy. By recognizing these as challenges that face all rulers, we can then analyze why some empires manage to address these challenges for centuries while others collapse within a generation or two. Note that, as with the flowcharts above, our ability to appreciate important similarities across cases allows us also to appreciate important differences: Confucian philosophy may have allowed East Asian rulers to achieve greater bureaucratic loyalty on average than rulers in other parts of the world.5

Nomads also have to worry about theft. Indeed, their mobile herds are a more tempting target than bulky stockpiles of grain. But they cannot rely on fortified cities as farmers can. And territorially defined states are of less obvious value to mobile nomads than to sedentary farmers. So nomads react to the possibility of theft by allying with other nomads in clans and tribes. That is, nomads and farmers face a similar challenge of protecting their food, but respond in different ways because of differences in physical mobility. Agricultural communities are usually characterized by cities and states. Nomadic communities are characterized by clan and tribal loyalties. Conflicts between nomadic tribes and sedentary states are of critical importance in the history of Eurasia (and to a lesser extent Africa). Students can usefully appreciate that both tribes and states reflect in part reactions to the same challenge. This is the purpose of organizing devices: to connect historical developments that might at first seem entirely distinct.

In-text Boxes

In-text Boxes have become common in world history texts. They can allow such texts to address an issue that is connected to a particular historical narrative but that transcends the geographical or temporal boundaries of a particular chapter. Such Boxes may then provide comparisons across different times and places and/or describe how a particular historical process unfolded across different times and places. They are necessarily a mild offence against the second type of "innocuous" identified above, for the student reading the Box will necessarily pursue the tangent before returning to the main narrative. Yet the Box clarifies an important point within that broader narrative and thus enriches the narrative even as it digresses.

The most obvious type of Box addresses historical processes that occur in many times and places. Malthusian population dynamics – with its prediction that population will grow to more than absorb any advance in productivity, impoverishing the bulk of the population and setting the stage for famine or epidemic or war – can be discussed early in a world history text. Then, as with the challenges addressed in the preceding section, comparisons can be drawn across various times and places in later chapters as to if/how Malthusian processes are at work. Epidemiological understandings of epidemics can likewise be outlined at one point in the text but later be drawn upon to compare and contrast various epidemics in human history.

To be sure, such Boxes introduce a bit of theory into World History. They might thus be accused of also violating the first type of "innocuous" identified above. But the sorts of theories addressed here are focused on just one or a couple of themes: They do not strive to place all of history within a single metanarrative. Moreover they can be seen as guiding a set of questions rather than leading to particular conclusions. A naïve reading of Malthus would imply that the incomes of the bulk of the population can never rise above subsistence in the long run. The historical record suggests instead that average incomes often rose for centuries. We are thus guided to ask why Malthusian mechanisms did not lead to absolute impoverishment.

Such Boxes might also address questions in historiography. Students should be aware that historical understandings change through time. But they should be steered away from a nihilistic view that historical understanding is thus just a matter of taste. We can discuss in general how historical understanding might be thought to improve as argument and evidence accumulate, and then guide students to observe this historiographic process across different times and places.

The second type of Box addresses particular historical processes that extend across time and space. Commodity history is particularly appropriate for such Boxes. We can, for example, devote a page or two to the history of rubber at one place in the text – perhaps when Cortes sends rubber balls to the Spanish court. We can discuss how Mayans and Aztecs made and used rubber balls, how Europeans then transplanted rubber plants to Africa and Asia (depriving growers in the Americas of potential monopoly profits), how bicycles and then automobiles greatly expanded the market for rubber, and even how scientists later developed synthetic rubber. We thus see in just a page or two a microcosm of world history as a whole: a cumulative process involving multiple types of people – rulers, soldiers, ballplayers, merchants, farmers, scientists, and more – across every inhabited continent over a period of centuries. And we see how political (including military), economic, cultural, technological and other themes interact. The complexity of world historical processes might be lost if the history of rubber were instead dispersed across several chapters.6 We can even speculate as to whether humans would have sought synthetic rubber if not for centuries of development of natural rubber. And of course we can treat many commodities in such a fashion: potatoes or coffee or sugar. In all these cases we might add to the overview provided in a Box by more detailed discussions across chapters.

Such Boxes can address manufactured goods as well as raw materials. Porcelain is particularly useful: We see first how a good from one part of the world becomes an article of global consumption over a period of centuries, and also inspires efforts at duplication. Clocks are another useful subject, for we can both trace the cumulative development of clock-making technology and discuss the broader impacts of precise timekeeping on various human activities.

Boxes can address a wide range of historical processes: the evolution of military technology and strategy; the spread of languages; the impacts of religions. In each case the purpose is the same: to provide a compact overview of the complexity of historical processes.

Last but not least such Boxes can directly connect world history to the world around us. One Box might address the place of world history within general education curricula. Another might discuss how world history can enhance one's appreciation of historical sites, museums, and art galleries around the world. Still others might briefly comment on contemporary repercussions of historical processes: the efforts of the Chinese government to build a modern Silk Road, or of the Indian government to reconstitute the ancient university at Nalanda, or the development of international expositions and sporting events. Such Boxes may be particularly important for students required to take world history as part of General Education requirements, and who may wonder how world history relates to their own lives.

Evolutionary Analysis

Special attention might be drawn to a particular type of historical process with wide applicability: evolution. Several of the themes that are commonly treated in world history – political and economic institutions, culture, technology and science, and art – evolve through time (and world history texts often also contain a chapter on the evolution of humans as a species). Humans do not, that is, usually change their entire institutional structure or technology or culture or art at one point in time. More commonly, small changes are made to existing institutions or cultural values or technologies or artistic practices. Some of these changes survive while others are rejected. Some of the survivors survive only temporarily but are soon forgotten. It makes sense then to employ the three key characteristics of evolutionary analysis – mutations, selection environment, and transmission mechanisms – in attempting to understand developments in these themes. That is, it is not enough to ask why certain institutions, values, technologies, or artistic practices emerged; we should also ask why they were selected and successfully transmitted (or not) through time. Indeed we will often find that many ideas were tossed around: It is not then the mutations that should most interest us (for there were many of these) but the selection among mutations.

As with certain types of Box, it might be worried that evolutionary analysis is not properly innocuous in the first sense employed above. Again, it can be stressed that evolutionary analysis guides a set of questions – Why did a particular mutation occur?; What was the selection environment?; and How/why was the mutation transmitted across time and space? – rather than precise answers. Indeed, by guiding us to ask three quite different questions of historical processes it steers us away from simplistic explanations. Note in particular that the selection environment for changes in one theme is the state of all other themes. A new cultural attitude is more likely to be selected if it aligns with political, economic, social, and technological realities. Evolutionary analysis does not by its nature privilege any theme but guides us instead to engage with thematic interactions of all types.

Evolutionary analysis can be explained once and then applied to any transformation in institutions, culture, technology and science, or art. Comparisons can then be drawn between the selection environments and transmission mechanisms of different times and places. For example, we can note how the introduction of writing changes transmission mechanisms thereafter.

An Example

The Ottomans (and Safavids) developed a practice whereby the sultan's sons were raised in isolation in the harem until the sultan died; one son was then taken from the harem to become the next sultan. Students can be surprised by a practice that seems purposely designed to ensure ineffectual leadership of the empire. Yet this is an institutional mutation designed to address another of the ruler's challenges: to keep the potential heirs to the throne from fomenting civil war, often before the existing sultan is dead. The mutation followed generations of Ottoman rule in which sons and other male relatives had regularly killed each other in savage wars of succession, and often attacked the ruling sultan. Why would this mutation be designed and selected? The sultan benefits from not having to worry about being attacked by his sons. And the sultan's advisors not only avoid the dangers inherent in civil war – where bureaucrats can lose their lives by choosing the wrong side – but are assured of a pliant ruler who will be dependent on advisors for knowledge of the outside world for at least the first years of their rule. The sultan and advisors are the selection environment for this mutation, at least in the short term. And they each transmit this practice to their descendants – along with stories of the internal conflicts over succession that had plagued the earlier empire. In the longer term, though, another sort of selection environment comes into play. The Ottoman Empire falls behind other empires both militarily and economically. Though there are likely many reasons for this, historians often point to a series of incompetent Ottoman rulers. The institutional mutation whereby generations of sultans were thrown unprepared onto the throne may thus have placed the Empire at a competitive disadvantage with other empires, and led (at least in part) to competitive selection for the eventual eclipse of the Ottoman Empire itself. Note that students might be asked to diagram the influences on and effects of the institutional innovation whereby the sultan's sons were isolated in the harem. And note that – as in the in-text Boxes referenced above – the broad outlines of a complex historical process, and the lessons that can be drawn from this, can be communicated in just a paragraph or two. Perhaps most importantly of all, students can move from surprise at this unusual practice toward an ability to place it within an understanding of how states have attempted throughout history to achieve smooth inter-generational transfers of power.

Organizing Devices and the Purposes of World History

Laura J. Mitchell, Ross E. Dunn, and Kerry Ward7 note that world history courses have not achieved the level of coherence of the Western Civilization courses from which they emerged. They argue that this is in part because the epistemological goals of world history are less clear. The purpose of Western Civilization was triumphalist: To trace a pattern of progress on many fronts from Mesopotamia through Greece and Rome to the British Empire and United States. The purposes of world history are less obvious.

We have deliberately not started with epistemology in this paper. But we have noted along the way that our organizing devices serve (at least) three broad goals:

· To communicate the cumulative effect of thematic interactions through time.

· To communicate the many ways in which societies have influenced each other through history.

· To communicate how all human societies have faced similar challenges, and allow us to compare and contrast how they have reacted to these.

Together these points guide us to appreciate that world history is a shared history: The ubiquity of both societal and thematic interactions means that we cannot understand the history of any theme or region of the world in isolation. And that shared history in turn reflects a common humanity: We have faced similar challenges across time and place and often responded in similar ways. Yet by appreciating these similarities we are also better able to appreciate novelty and innovation. We may thus feel a particular attachment to particular episodes or peoples, but are guided away from xenophobia or ethnocentrism. All human societies have acted laudably at times and stupidly or despicably at others. This is our shared heritage.

These are arguably the sort of lessons that world history should and does aspire to communicate. Mitchell, Dunn, and Ward8 (2016, 95) cite both Jerry Bentley and William McNeil as arguing that world history should cultivate an identification with humanity as a whole. Yet of course the glory of history lies in the ability to appreciate both commonalities and uniqueness.

One important further lesson involves the place of individuals in history. Jeff Pardue9 notes that students often try to personalize history. One can teach them about how impersonal forces of politics and economy and technology interact but they will still attribute historical transformation to heroic actors. It is thus critical that world history has a place both for impersonal societal-level forces and for individual actions. If we squeeze individuals out of world history – which is easily done when trying to encompass the history of the world in a few hundred pages – we can hardly be surprised if students insist on putting them back in. If, however, we model how individuals interact with societal-level forces through history, we can hope that students will gain a nuanced appreciation of the role of individuals in history. Our organizing devices do have a place for both individual-level and societal-level influences. Note the role for charismatic leaders in Figure 2: We can potentially use the personality dimensions identified by psychologists in order to compare different historical actors – and their impacts on history. The discussions of challenges facing different types of human actors place (types of) individuals front and center in history. Evolutionary analysis has an important place for individuals as sources of mutation, but reminds us also to look at the (generally) collective action involved in selection.

Interdisciplinarity

We mentioned interdisciplinarity above. Patrick Manning10 has argued that one of the key purposes of world history is to integrate understandings from different disciplines into coherent historical accounts. He applauds, for example, the integration of biological and social understandings in discussions of the Columbian Exchange. He urges the examination of cross-thematic influences and effects that we have stressed above.

The word "interdisciplinary" is often invoked in the world history literature. In part, this reflects the fact that interdisciplinary scholarship and world history scholarship must both extoll the virtues of breadth of knowledge within an academy that tends to stress narrow specialization. Unfortunately, forums in journals in the field that self-describe as "interdisciplinary" are often "multidisciplinary": they juxtapose insights from different disciplines (a valuable practice in its own right, to be sure) but do not integrate these. It is worth noting, then, that the organizing devices mentioned above accord with three of the four main strategies for integration identified in the literature on interdisciplinary research.11 The strategy of "organization" involves visually mapping the connections between phenomena studied in different disciplines. The strategy of "redefinition" recognizes that different disciplines/scholars attach different meanings to the same terms, and advocates clarification of terminology. The emphasis on thematic interactions noted above presupposes clarification of what we mean both by broad themes such as "culture" and the many phenomena that comprise "culture." The strategy of "theory extension" involves adding the phenomena studied by one discipline to a theory that incorporates phenomena studied in other disciplines. Evolutionary analysis is particularly well-suited to this task. [The fourth strategy, "transformation," involves placing seeming dichotomies on a continuum: This strategy too can be usefully employed in world history if, say, some economists explain migration decisions entirely in terms of rational calculations and some sociologists appeal entirely to non-rational pressures of family and culture and networks; we can appreciate that humans are neither perfectly rational nor non-rational.]

Note that these strategies often allow us to transcend historical controversies. Some scholars may describe the rise of kings as a voluntaristic process in which farmers cede power in return for protection. Other scholars may instead see kings as achieving power through the arbitrary exercise of force. We can see these explanations as complements rather than substitutes. Our organizing devices, then, are useful not just when historians agree but also when they disagree. And thus we can aspire to excite our students not just with history itself but with how history is studied.

Skill Acquisition

In addition to communicating ideas such as those surveyed in the preceding sections, world history courses are generally expected to impart important skills to students.12 Our organizing devices aid skill acquisition also:

· The very act of organizing world history guides students to develop the more general – and critical – skill of organizing complex information into some coherent whole. We should thus be explicit about our organizing strategies.

· Our organizing devices suggest a common set of questions to ask of different historical episodes: what themes are interacting?; what challenges are being faced?; what mutations, selection, and transmission mechanisms are implicated? As noted in the preceding section, these organizing devices also allow us to transcend scholarly disagreements. These practices should aid in the development of critical thinking skills. Again, we can aid skill acquisition by being transparent about our analytical approach.

· Students often perform comparisons poorly, referencing different aspects of the cases supposedly being compared. Clarity with respect to the themes being addressed and how these interact should aid students in learning how to perform meaningful comparisons. By explicitly modeling good comparative practices, we enhance our students' skills.

· More specifically, extensive use of flowcharts enhances what is commonly termed visual literacy.

Of course, there is a limit to how much skill mastery can occur in any one course. Different instructors may wish to emphasize different skills. Ideally, these skills will be reinforced in other courses. Nevertheless, it is important to appreciate that the organizing devices outlined above can aid students as they master important skills.

Drawing Lessons from World History

Each of the organizing devices discussed above can also inform attempts to draw lessons from world history.13 The common practice of drawing lessons by analogy can be problematic: Comparing any world leader that does not oppose aggression by another to Neville Chamberlain makes sense only if the current situation mimics that of the mid-1930s. Our flowcharts remind us of the complexity of historical processes and guide us instead to speculate on how our themes are likely to interact in future. Our Boxes remind us that – while history never repeats itself – certain historical processes do recur with some frequency: We might ask ourselves, for example, about how cultural toleration and political stability have been related in the past and speculate on how that relationship will unfold in future (keeping in mind how culture and polity will interact with yet other themes). Evolutionary analysis guides us to inquire into the nature of selection environments and transmission mechanisms: how do institutions and culture shape the kinds of public policies likely to be adopted – and what sort of changes in institutions or culture might thus prove beneficial? Our understanding of how the challenges faced by a variety of human actors have been addressed historically can guide us to speculate on how such challenges might be better addressed in future.

We noted above that our organizing devices often guide a set of questions to ask of historical episodes. We see here that these same questions can be turned toward the future. We can ask about how evolutionary processes are likely to unfold – and may speculate on how selection mechanisms themselves might be altered. We can wonder about what sorts of thematic interactions might prove particularly important. And we can ask how the challenges still facing the actors we have followed through history might be addressed. In all of these exercises we can draw on our understanding of the past to inform our expectations of the future. But our emphasis on evolutionary analysis and cross-thematic interactions steers us away from simply extrapolating particular trends far into the future.

It is thus feasible to close a textbook in world history with a chapter devoted to drawing lessons. Given the complexity of history we should of course be humble in any attempts to draw lessons. But our organizing devices allow us to structure educated analyses of how we might draw on lessons from the past to shape our future. Such a chapter would lend further coherence to the subject matter by attempting to discern patterns in world history. Importantly they connect our shared past with our shared future. Such material may prove especially valuable to those students who are unsure why they have been required to take world history.

Organizing Devices as Teaching Aids

All of the organizing devices we have described are compact. They may collectively only comprise a few percent of the space in a world history text. Yet instructors may find them particularly useful in the classroom. A PowerPoint slide of a flowchart might guide class discussions of a particular historical episode. Students could be invited, for example, to compare the relative importance of different boxes and arrows, or suggest modifications to the diagram. Slides of previous flowcharts may then be used to remind students of connections to earlier chapters. A PowerPoint slide of the challenges facing rulers could be used to draw comparisons across different episodes of imperial rise and decline. A PowerPoint slide of the challenges facing merchants could be used to discuss in what ways the East India companies were the same as earlier merchant networks and in what ways they were different (e.g. long distance trade by sea encouraged the development of trading forts, whereas travel overland generally required reaching agreements with political authorities.). A PowerPoint slide of one of the in-text Boxes could be used to highlight how a particular historical process involved many different agents from many different countries/continents, each building upon the actions of predecessors. And evolutionary analysis provides a series of simple questions – Why did a mutation occur?; why was it selected?, and how was it transmitted through time? – that can be employed to guide class discussions.

A Quick Response to Stephen

Stephen Morillo in his paper in this Forum14 raises some questions about a couple of the points made above. I thank him for the opportunity to clarify my approach. In so doing we will apply some of the techniques of interdisciplinary analysis mentioned above in order to attempt to achieve (greater) consensus.

First of all he urges us to a broader reflection on how to organize our field conceptually rather than just how to organize for the purpose of communication to students. I concur wholeheartedly. I argue elsewhere15 that we can pursue a set of themes (and especially interactions among these) that embrace all subjects addressed by social scientists and humanists (see below). When a world historian investigates some novel interaction – say between gender relations and military strategy – this new understanding has a natural place within an organizing structure that embraces all themes. Though we must necessarily choose which historical processes and events to stress to our students, we should as a field have an organizing structure in mind that encompasses all possible historical explorations. One important advantage of such an approach is that we can then more readily encourage students to investigate topics that we have not had time to cover in class – as both Stephen and I do in our books.

He then worries that biological evolution will be used as a template for addressing processes of social evolution. It is critically important to address the key differences between biological and social evolution: that "ideas" are harder to study with precision as a unit of mutation than "genes," that social mutations are necessarily less random than genetic mutations, and that "interbreeding" is much more feasible in social than in biological evolution (at least before genetic engineering). The key similarity between the two types of evolutionary process is that many mutations are generated of which only a small minority are selected. This guides us as historians to look beyond why a particular idea might have been generated to wonder why it was adopted. We are also guided to study how ideas are changed in transmission across both time and space. It is perhaps noteworthy that evolutionary theorizing had been applied to social processes before it was applied to biological processes, and that biological evolutionary theory proved very important and useful for decades before it was appreciated that genes were the unit of mutation and decades more before the nature of genes was well understood.

I totally understand Stephen's concerns that evolutionary analysis has often been mistakenly applied in the past and thus associated with ideas of inevitable progress and of ethnocentrism. As he suspects, I am careful to avoid such confusions: Indeed I address both directly. And that is one reason that I stressed above that evolutionary analysis guides a set of questions rather than answers. I would argue here that evolutionary analysis as I employ it works against the sort of misguided conclusions that worry Stephen. In the Ottoman example provided above we can see how an evolutionary process encouraged imperial decline and the eclipse of the very sultans and advisors who selected the mutation. Note here that evolutionary analysis can be usefully applied to a series of specific historical transformations; it should not be used to shape the narrative as a whole. In appreciating both why different societies selected different mutations, and how and why ideas change as they move across time and place, we discredit simplistic celebrations of the superiority of one civilization over another. The best response to misguided interpretations of history is to provide more accurate and readily-appreciated interpretations. It would be a tragedy if we abandoned a very useful form of analysis simply because it has been misused in the past.

Our disagreement regarding meta-narratives seems to be primarily semantic: The meta-narratives I seek to avoid are what he terms "bad meta-narrative" whereas what he calls "good meta-narrative" strikes me as a quite different animal. I hope/think that we would both see as "bad meta-narratives" any approach that explicitly forbade the exploration of plausible historical explanations. But Stephen raises here an important point about how world historians must necessarily generalize and thus choose among many possible generalizations. He worries that is not possible to engage with a large number of themes or processes in one book. I would counter that we need as world historians to address each of the following in some depth: human psychology, culture, politics, economy, social divisions, demography (and health), technology and science, art, and environment. These are each important in their own right, and they each interact with all of the others. We create a seriously biased and incomplete history if we exclude one or two or five of these from consideration for reasons of expositional convenience. My flowcharts and other organizing devices allow me to engage a broad range of themes in a manner that makes sense to students. This does not mean that each theme has to be addressed for each historical episode addressed – though students are often invited to speculate on what might be added to a particular historical account. But I argued above that one of the lessons we should seek to impart to students is that history involves a complex and cumulative interaction across all of these themes. We cannot achieve that critical goal if we simplify our accounts too much. [I thus worry a bit about the "model" that Stephen speaks of that guides his own book, but imagine that his model is a broad and flexible one that need not necessarily guide us away from important insights as "bad meta-narratives" do.] But Stephen and I likely agree here much more than we disagree: we both recognize a tension between generalization and specificity and may pragmatically make different choices.

Stephen and I also agree about narrative flow, I think. My second principle is not meant to imply that we can never take the reader off on an important tangent: My organizing devices each do that to some extent. The point is that the narrative must still cohere, and the reader must be returned to it expeditiously before they have forgotten what was happening. As Stephen notes, a well-placed text box can serve to place the narrative in some broader context: He thus uses his to relate a particular narrative to his organizing model. Though I embrace a wider range of types of digression my intent also is always to provide greater context for the narrative in question.

Stephen then makes a point that is absolutely crucial: that we want the students to learn not just the narrative but what the narrative means. I think my second principle of being innocuous is still important in achieving the first goal. But Stephen is entirely correct that we need to think beyond the narrative. There is thus another tension that the author of a world history text must face between providing a clear narrative and yet also examining that narrative. Stephen and I would agree that a world history text must be more in the end than just a series of compelling stories. In addition to the organizing devices described above (and the fact that my narratives themselves do not just tell a story but analyze while telling), I would agree with Stephen that a world history text should have introductory material that guides the student as to how narrative will be placed in context. I have also suggested above the inclusion of a closing chapter that attempts to draw lessons from history. My hope is that students thus not only learn the narratives but gain a deep appreciation of how the histories of different times and places are related; these understandings in turn can inform their understanding of their own personal identity and place in history, and of the world in which they live.

A final point: Stephen and I concur that we should let our students know what we are doing. They should know both our goals and our strategies.

As stressed in my introductory essay to this forum, this is an exciting time in world history. Stephen and I have pursued different paths but seem to agree on the value of organization, many of the goals of organization, and even some strategies for achieving these goals.

Concluding Remarks

We have outlined a handful of simple organizing devices that can lend coherence to World History courses. They are each innocuous in the dual senses that they do not (much) force history into some meta-narrative nor (much) interrupt narrative flow. In addition to providing coherence, these organizing devices communicate the idea of a shared history reflecting our common human nature and the ubiquity of cross-societal interactions – yet at the same time allow for appreciation of both societal and individual novelty. Students learn that history is a process of cumulative thematic interaction. Students gain both a structure for remembering the historical narrative and a greater appreciation of the value of world history. And they master important skills: organizing complex information, drawing comparisons, critical thinking, and visual literacy. Instructors will find that each of the organizing devices is useful in the classroom for guiding discussions and connecting one classroom discussion to previous discussions. Both instructors and students are then aided in drawing lessons from world history.

Rick Szostak is professor and chair of the Department of Economics at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. He is the author or co-author of 14 books including Technology and American Society: A History (third edition in progress for Routledge) and Interdisciplinary Research: Process and Theory (2017). He can be reached at rszostak@ualberta.ca

Appendix

|

|||

| Figure 3 | |||

1 Jürgen Osterhammel, The Transformation of the World: A Global History of the Nineteenth Century (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014), xv.

2 Patrick Manning, "Locating Africans on the World Stage: A Problem in World History," Journal of World History 26, no.3 (2015): 605-37, especially 612-3.

3 Benjamin Reilly, "Mapping Student Learning: Course Assessment using Concept Maps in a World History Survey Course." World History Connected 10, no.2 (2013).

4 The fact that we draw comparisons across time and place for certain types of historical actor does not prevent us, of course, from appreciating other types of actor who appear only in some societies. Indeed it encourages us to appreciate their uniqueness.

5 The argument here would be that Confucian philosophy urged bureaucrats toward loyalty and honesty.

6 Sven Beckert celebrated the value of commodity history in these respects in his address to the World History Association conference in Ghent in 2016; Boxes allow the contribution of commodity history to a greater world-historical sensibility to be highlighted within a world history textbook.

7 Laura J. Mitchell, Ross E. Dunn, and Kerry Ward, The New World History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2016), 4-5.

8 Mitchell, Dunn, and Ward, The New World History, 95.

9 Jeff Pardue, "Keeping the 'Story' in World History: Theme, Narrative and Student Engagement in the Survey Class," World History Connected 11, no. 3 (2014).

10 Manning, "Locating Africans on the World Stage."

11 See Allen Repko and Rick Szostak, Interdisciplinary Research: Process and Theory, 3rd. ed. (Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2017).

12 Lendol Calder, "Introduction" [To a Forum on introductory survey courses in world history], World History Connected 13, no. 2 (2016).

13 Rick Szostak, Making Sense of World History (In Progress). Lists of the flowcharts, discussions of challenges, and Boxes (and some examples of each) can be found at: https://sites.google.com/a/ualberta.ca/rick-szostak/research/making-sense-of-wh

14 Stephen Morillo, "Organizing World history," World History Connected, February 2018.

15 Rick Szostak, Making Sense of World History (In Progress).