Interview with Michael G. Vann, Professor of History, Sacramento State University, author of the new graphic history, The Great Hanoi Rat Hunt: Empire, Disease, and Modernity in French Colonial Vietnam.

Conducted by phone, transcribed and edited by Marc Jason Gilbert, Editor of World History Connected, May 20, 2018.

|

|||

| Michael G. Vann, on location for the short film "Cambodia's Other Lost City: French Colonial Phnom Penh." | |||

Gilbert: Michael Vann received his PhD in History from the University of California, Santa Cruz, in 1999. He can be reached at mikevann@csus.edu.

Gilbert: I first met Professor Michael G. Vann in café in Siem Reap, where I was conducting the first of many workshops and conferences on the places of Cambodia, Vietnam and Southeast Asia in world history conducted under the auspices of Pannasastra University (in Cambodia) and VNSSH—the faculty of Vietnam National University in Hanoi devoted Social Sciences and Humanities. Mike, as he prefers to be called in conversation, quickly became a valued contributor to these conferences. I learned then that, like myself, Mike had entered graduate school at a time when there were no graduate programs in world history. However, that did not deter either of us from creating our own degree path, with the support of mentors eager to add a global dimension to their own fields; mine in South and Southeast Asian History, and his mentors in French and French colonial history. This interview begins with a discussion of his journey into world history and moves to address the innovative work he is currently pursuing in graphic history and comparative remembrance of war and genocide in Southeast Asia.

Gilbert: Michael, what sparked your interest in World History?

Vann: I was interested in world history and becoming a world historian before I had even had heard the term "world history." All the kind of questions that I wanted to ask about history where all about global intersections, whether they were tied into the Cold War or tied into the era of high imperialism. I was deeply interested in the way that Europe and the United States interacted with Southeast Asia, and the impact of China and Japan on these regions. I was fortunately enough to be in a graduate program at UC Santa Cruz in the early 1990s that included world historians Edmund "Terry" Burke and recent AHA President Tyler Stovall. Terry Burke was a pioneer in world history who started working on France and Morocco along with his friend Ross Dunn (historian of Ibn Battuta's travels) and others to help create world history as a recognized academic field. Tyler Stovall started off as a traditional historian of France doing social history and was training me as such. But he began to ask more and more of these transnational questions of cross-cultural interaction regarding issues of race in French history. Their work inspired me realize that there was this whole field of world history where people took the nation state paradigm and cast it aside and looked at these global patterns of interaction. That was a real eyeopener for me. I was lucky enough to have graduate school colleagues such as former WHA President Rick Warner, so Santa Cruz was a really exciting place to become a world historian in the 1990s.

Gilbert: Many of us let our dissertation topic do the walking. Where did it lead you?

Vann: I was working with Tyler Stovall in French history and I decided I wanted to do an aspect of French history that had to do with colonialism. Since Tyler was originally trained as an urban historian and wrote two excellent books on Paris, he was steering me in that direction. I thought that by picking a colonial city I could work with a site where I could examine global interactions and bring that city into the history of race and racism in French history. As a surfer from Hawai'i my first choice was Papeete [Tahiti] which Stovall promptly vetoed. He said, "I know you, if you go to Tahiti you're never coming back." As this was the 1990s, Algiers was out of the question as the horrific civil war would make research difficult. I looked through the literature and found that Hanoi had not been so closely studied as to preclude dissertation work, so colonial Hanoi became my dissertation topic. I also wanted to contribute the American knowledge about Vietnam outside of the war.

The timing was good in terms of funding because the United States and Vietnam were moving towards full diplomatic recognition. Bill Clinton was leading that push. There was no Fulbright to Vietnam at that point. So I applied for a Fulbright to France to study Vietnam and I think that in 1994-95 when I applied for that Fulbright it was seen to be a very shrewd diplomatic move. This was a way for Fulbright to make a gesture to Vietnam even though there was no official Fulbright for Vietnam at that time.

Gilbert: Ironically, I was one of many pushing President Clinton to normalize relations with Vietnam because that was a necessary step before the Fulbright program could operate in Vietnam. When I wrote to him about that, I got a reply within two weeks—so focused was he on that issue. Even many years afterwards, he literally could not stop talking to me about that effort, he was so proud of that achievement. How did your Fulbright-funded work lead you further down the road to world history?

Vann: When I began that work—a history of Hanoi under French occupation—my initial focus was quite traditional—on urban planning: what and when buildings were built, etc. To be honest with you, about six months into the research project in the French colonial archives [Les Archives nationales d'outre-mer] in Aix-en-Provence, I began to get really, really bored looking at tax documents, road building documents, and cadastral reports. I started to wander in the archives and looked for other dossiers that just seemed like they had interesting titles which I could look at as part of my daily allotment of ten dossiers to examine each day. It was during that process that I saw an index card marked "destruction of animals in the city." That sounded interesting! So I pulled up the relevant dossier to entertain myself on a long afternoon.

And when I opened it up it was about 100-120 sheets of paper all printed up with daily totals of rat kill. Saying X number of rats killed in the First Arrondissement (urban district), Y number of rats killed in the Second Arrondissement. I looked through these sheets and they covered a period from about March or April 1902 all the way to July 1902. My jaw dropped as I read that on the first day 500 rats killed and then 700 on the second, and then 1,000, and then they rose to 5,000, 8,000 and at one point over 20,000 were killed in a single day in Hanoi! I thought this was incredible, the killing of hundreds of thousands of rats. What was going on? There was little in that dossier explaining what these figures meant in terms of policy.

So I set about the task became trying to find other sources in the archives to triangulate and fill out the story. I found a few other archival sources, some memoirs and medical records, first in Aix-en-Provence, then in archives in Marseilles, Paris, and Hanoi.

In the past, most colonial historians would have stopped there: with an examination of how and why the French sought to eradicate all the sewer rats in Hanoi. However, by the 1990s, I already numbered among a growing number of scholars who were not satisfied with studying just the actions of colonial actors and were determined to explore the colonized as well as the colonizer on their own terms, as well as in the context of colonial policy.

Over the course of about six years, I dug deeper into this question until I discovered an incredible story of Vietnamese agency within the history rat eradication. It turned out that the Vietnamese outsmarted the French colonial state. When the French authorities asked them to bring in dead rats for a bounty, the folks down at Hanoi's city hall realized that bringing dead rats into the city center was a bad idea: you don't want thousands of dead rats at city hall. As a result, they told Vietnamese rat catchers to just bring in the tails of the rats, at which time they would receive what amounted to a penny to per tail.

The French colonial health authorities thought that they had really figured out this great plan because they soon got people bringing thousands of tails of killed rats. But after about three months of this they discovered that just outside of Hanoi there were rats running around with no tails! And then further investigation revealed to them that there were rat farms established by locals in suburban villages. They were farming rats for their tails to make money from the French authorities! The French later discovered that there was a black market in trafficking rats all around Tonkin, northern Vietnam, to bring the tails to Hanoi to rake in the bounty paid on each tail. And it was just an incredible story of the Vietnamese resisting colonialism that had implications for our understanding of the actual nature of the French colonial state and the place of Hanoi within it.

In my study of Hanoi as a colonial city—in parallel to studies of colonial cities elsewhere, I learned of its importance as symbol of the preeminent strength of the colonial state and its power over its subjects. Hanoi's very buildings were designed to communicate order, permanence, and the solidity of the French state. Hanoi served as such a symbol, but its actual status was precarious, rather than solid. Even as Governor-General Paul Doumer laid the groundwork for modern French administration in Indochina (1897-1902), pirates on the Red River threatened the security of Hanoi, which sat on its banks. In theory, Hanoi was designed to show the limitless power of the colonial state, but in reality, the French administration rested on a shaky foundation, with the story of the Vietnamese black market in rats serving to expose how little the French were actually in charge even of their own capital city.

|

|||

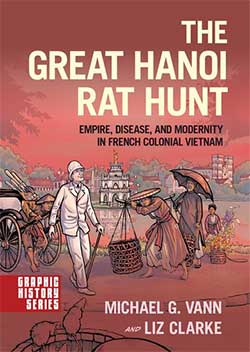

| The Great Hanoi Rat Hunt: Empire, Disease, and Modernity in French Colonial Vietnam (Oxford Univesity Press, 2018) | |||

Gilbert: But this is a world history piece. How do you make the link between studying one colonial city in Southeast Asia and the larger world?

Vann: Well, by exploring Hanoi's relationship to empire, disease, and modernity. First, France's colonization of Vietnam illustrates world historical forces at work. France's industrialized military conquered Vietnam as part of its imperialist economic expansion, described by Lenin as the "highest stage of capitalism." Second, throughout world history disease has been spread by empire and immigration, cases of people in motion. Ninetieth century imperialism was no exception, with local epidemics of diseases like cholera and the bubonic plague becoming global pandemics. French medical authorities, including researchers like Alexandre Yersin and Jean-Paul Simond, identified rats and fleas as the vector in the spread of the disease. In Hanoi officials tried to kill all the rats in the city because they feared the arrival of the plague from China.

And how was the disease getting there? Through the third factor: the modern global network of industrialized transportation, including steamships and railroads. Boats from Hong Kong and trains from Yunnan brought rats infested with fleas who were infected with the plague bacillus into Hanoi and other colonial cities. When they got to Hanoi, many scurried into the brand-new sewer system, ironically itself a great symbol of French modernity, where they discovered an ecosystem free of predators where they could breed. What I call the Great Hanoi Rat Hunt was an attempt to prevent a plague epidemic in the city. The colonial officials were responding to an unintended consequence of their modernization schemes.

Gilbert: And you turned this research into a graphic history based on archival research and now part of an emerging genre, a series of which is published by Oxford University Press. How did that come about?

Vann: Once again it was a case of me being bored in the archives and looking for something fun to read. During my work at the Vietnam National Archives in Hanoi in the 1990s, I also worked in the National Library of Vietnam next door. There I examined colonial era newspapers for more traditional urban history stuff, social history, but when I got tired of statistics about construction projects or road building or demography I would read the cartoons in the newspapers. I found them to be a treasure trove of information about colonial life, including a collection of very risqué or ribald cartoons that were really open and straightforward about life in the colonial city, particularly with regard to white male sexual practices, prostitution, and various forms of relationships with Vietnamese, Chinese, and Japanese women. These cartoons seemed to me to be previously ignored primary sources that were much more honest and straightforward than the mediated official voice presented in official archival documents. I found these cartoons and this newspaper to be incredibly rich and more honest sources for exploring colonial culture. My thinking was akin to cultural anthropology as interpreted by Clifford Greetz, who urged investigators to "employ the power of the scientific imagination to bring us into touch with the lives of strangers."

Gilbert: And where did these cartoons lead you?

Vann: They led me to write two articles and a short book of translated, annotated, and explicated colonial cartoons (from the Saigon press in 1913) as an archival source. And then I was in my office one day wondering what my next project was going to be. As I was looking at a copy of The Colonial Good Life, my book of Saigon cartoons on my desk, I saw Trevor Getz's pioneering graphic history, Abina and the Important Men, sitting next to it. I just had this flash of "Oh wait a minute! I should be composing a graphic history! This would be great manner of sharing some of the things I'd been working with regard to colonial Hanoi." And then, almost immediately, it came to me: The Rat Hunt! I said "Oh, the rat hunt. I could do a graphic history of the Hanoi rat hunt." And I did. I contacted Oxford University Press and talked with its head of History, Charles Cavaliere, who has been a supporter of scholarship in world history since its inception, first at Pearson and then at Oxford.

In the space of a few email exchanges Charles and Oxford were on board with this project. Almost before I knew it, I was working with Liz Clarke, the artist for most of its new Oxford graphic history series. This proved to be one of the most rewarding and exciting research experiences I have ever had. For years I had been looking through these documents, collected postcards, lithographs, and maps of the city. I was taking those sources, putting them together, and writing them out in to prose. Working with Liz, I'd say "Here is how I describe this, and here are a couple of images." She would say, "do you want me to put in these aspects of the historical context on this specific street corner in Hanoi? Like this?" "Yes!" I would invariably say, amazed at what she had done. Working with Liz enabled me to visualize political meetings or day to day things like prison laborers who did a lot of the sanitation work in Hanoi at specific sites, with Liz using postcards and the other images to create the backgrounds. It was seeing what I had been writing as academic prose come to life! It was difficult to put my excitement into words the first time that I got an email with a series of her sketches. I hope the final product, The Great Hanoi Rat Hunt: Empire, Disease, and Modernity in French Colonial Vietnam, servers to spread my enthusiasm to others for telling important history in creative ways.

Gilbert: Would you be interested in doing another graphic history?

Vann: That is a possibility. I would love to do a history of cholera. Last year, 2017, was the bicentennial of the cholera pandemics. There is a publication series that addresses graphic medical history. It would be fantastic to so a history of cholera as a product of the era of colonial globalization, linking disease to empire, capitalism, and industrialization.

However, I am now working on a comparative history of Southeast Asian museums about the Cold War era. I'm fascinated by the differences between the Indonesian, Vietnamese and Cambodian representation of Cold War violence. Vietnam, Cambodia and Indonesia are all ideologically diverse, but of the three, it is Indonesia that most valorizes the violence of the period, building what is a shrine to the justification of the killing of at least 500,000 but perhaps as many as 3,000,000 civilians slain, tortured, and/or imprisoned in the 1965/1966 anti-communist coup. Unlike museums in Vietnam and Cambodia which teach messages of reconciliation and healing, Jakarta's Museum of the Indonesian Communist Party's Treachery continues the angry (and deceptive) Cold War ideology of the Suharto dictatorship (1966-1998), even after the re-establishment of democracy 20 years ago. Furthermore, Ho Chi Minh City's War Remnants Museum and Phnom Penh's Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum are major tourist attractions with thousands of visitors a day but the locally well-known Indonesian site receives little attention from international visitors. Indeed, in 2017 I was denied entry to the museum (which I had visited several times before). Evidently, army intelligence is worried about new historical research on the killings and decided to ban foreigners from the museum. Ironically, their move validates the significance of my research.

Gilbert: Do you think your research projects on rat hunting in Hanoi and Southeast Asian Cold War museums have value for the teaching of world history?

Vann: I do. I use both in my courses in world history. Either lecturing or writing material for classroom use, such as my graphic history, I bring in my scholarly research. Students seem to enjoy seeing their teacher as an active scholar hunting sewer rats in the archives or visiting controversial museums. Not quite Indiana Jones… but the idea of the historian working in the field is important.

I've been fortunate to have a regional specialization that I find so fascinating and I try to bring my enthusiasm to my students as best I can. Southeast Asia is so rich a region for illustrating world historical forces. The origins of capitalism can be seen in the evolution of the Dutch investment in spice production of Southeast Asia: their occupation of what is now Indonesia offers a classic example of European resource exploitation; their independence struggle offers an alternative to the many contemporary communist-led anti-colonialist movements, while Japans' effort to bring Indonesia with its "Asian Coprosperity Sphere" is a fine example of how Japan sought through propaganda to justify its imperial project at home and abroad. The Khmer Rouge's violence in Cambodia offers an opportunity to place genocide in global perspective, while Vietnam's modern history is an excellent introduction to colonialism, the First World War in Asia, the Great Depression, the Second World War in the Pacific, 20th century social revolution, the Cold War, post-war era of decolonization, and the reforms in the Communist world that have created what I jokingly call "Market-Leninism." It could be argued that such examples can be found elsewhere, but the fact of the matter is that the United States is home to vast diasporas of Southeast Asian peoples, particularly in large states such as California and Texas. The cultural and historical heritage of these students must be taught. But sadly Southeast Asia is still poorly taught there and sometimes not even addressed.

Gilbert: This is a problem World History Connected has often addressed and is grateful both for your contributions to the field and for your commitment to the common task before us: lifting Southeast Asia from the generally short shrift it receives in world history survey courses into the mainstream of classroom instruction. Thank you, Mike.

Vann: Marc, thank you for the chance to chat and for your great work with World History Connected and the World History Association.

[Breaking News: Michael has just won a Fulbright to Cambodia to teach at Pannasastra University in Siem Reap and pursue his research on the Cold War era museums. Readers are encouraged to apply for a Fulbright: one does not have to be a research scholar to apply! For a list of health professionals, teachers, and others welcome to apply, please go to: https://www.cies.org/ for information.]

|

|||

| Marc Gilbert and Michael Vann in Hanoi. | |||