FORUM:

Gender and Empire

(Colonial) Intimacy Issues: Using French Hanoi to Teach the Histories of Sex, Racial Hierarchies, and Geographies of Desire in the New Imperialism

Michael G. Vann

This essay offers some reflections on uses of my gendered analysis of the colonial encounter in French Indochina to teach the sexual history of empire. Drawing upon previously untapped sources in Vietnam's National Library pre-1954 collection, "Sex and the Colonial City: Mapping Masculinity, Whiteness, and Desire in French Occupied Hanoi," my article in The Journal of World History engages critical theories of masculinity and whiteness to create a thick description of life in the colonial city.1 The article argues that imperialism's racial, gender, and class hierarchies combined with the French Third Republic's (1871–1940) paternalism and misogyny to give French men unprecedented power over colonial Asian subjects, especially Vietnamese women. This intersectionality of privilege created an openly predatory sexual culture during a time when French Hanoi's white community was overwhelmingly male. French men's desires for inter-racial intimacy both crossed the colonial color-line and reaffirmed white imperial supremacy.

Though this article stems from scholarly research, my analysis, methodology, and conclusions have a variety of classroom uses. This subject need not be confined to undergraduate and graduate courses on empire or sexuality. Rather, high school and college level world history surveys can integrate my argument and documents into lessons on the New Imperialism. We can use my source material, cartoons from the French colonial city, to teach the ways in which French men understood their power both in the city and throughout colonial Asia. Racial hierarchies of desire were central to colonial white supremacy. Obviously, certain care should be taken when teaching sexuality. However, in the age of #metoo it is increasingly important to critique how historically specific gender power arrangements impacted sexuality, sexual practice, and social justice.

As a case-study for teaching the New Imperialism, Hanoi allows us to expand our geographical coverage beyond traditional Anglo-centric frameworks. This French city in colonial Southeast Asia offers an example from outside of the British Empire which so heavily dominates the scholarship and teaching of imperialism. Insights from Hanoi have relevance to world historical discussions of race, gender, and empire. French occupied Hanoi was but one manifestation of global white supremacy at the turn of the 20th century.

Finding Sex in the Colonial City's Archives

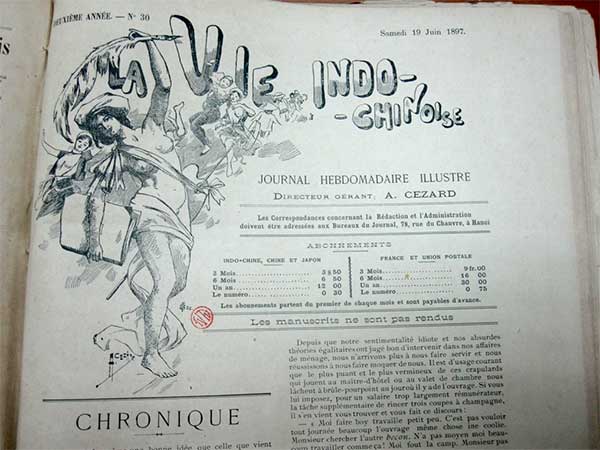

In the pages of some of Hanoi's French language newspapers in the mid-1890s, one would find caricatures, cartoons, and poems about life in the colonial city. Bored French administrators, officers, and civilians penned jocular critiques of local politics, frustrations with the various shortcomings of life in the colonial tropics, and a wide range of comments on the cities' illicit diversions such as drinking binges, opium use, and prostitution. The weekly La Vie Indo-Chinoise, which ran from November 1896 to April 1898, stood out as a particularly ribald collection of images, verse, and prose. Regardless of their dubious contribution to French art and literature, these cartoons are extremely useful for cultural historians of the colonial encounter. They are artifacts of conversations amongst French colonial men. As such, they display an openness and frankness lacking in the official representations of the French empire and the all too commonly optimistic boosterism or misleading propaganda. Contemporaries praised the authors for capturing the realities of colonial life.2 By probing this seemingly banal and untapped source of documents, we can reconstruct the male French colonial self-image in Hanoi and how the colonizer saw the colonized and the colonial city. More specifically, these sources allow for a cultural history of white male sexual desire that can be literally mapped onto colonial Hanoi, as well as various port cities in Asia during the age of empire.3 Such a territorialization of sexual practice and erotic fantasy allows for a history of intimacy within the profoundly unequal power relationships of the colonial encounter, a world historical phenomenon at the turn of the twentieth century.

I wish I could say that I found these useful primary sources by following a carefully planned research methodology or clear theoretical model but actually it was dumb luck and a restless mind. The truth is that initially my approach was a traditional urban history. I looked at the archival holdings of city planners such as tax records, road building reports, and maps of sewer and water systems. First, I spent over a year in the colonial archives in Aix-en-Provence, France, and then I went to investigate the remaining French archives in Hanoi in 1997. As one of the first generation of Americans allowed to conduct research in Vietnam, it took a number of weeks to receive official clearance to access the collection. Rather than wasting my time enjoying life in the beautiful city, I spent my time in the National Library as it did not have restrictive regulations. Here I found not only a quiet respite from Hanoi's noisy traffic, but I also discovered the library held a collection of century old French newspapers. Thinking they might be useful I requested several volumes. The librarians were visibly annoyed to have to access the dusty and moldy old papers in a section of the buildings rumored to be home to a colony of rats (the subject of my new book, by the way). As I looked through these locally produced newspapers I found lots of useful urban history material, but I also got very, very bored. One can read only so many tax reports or construction statistics. To amuse myself and to pass the time, I began to read through the rest of the newspapers and found the cartoons that became the basis of this research project. For reasons that I will discuss below, they offered more than an elusive and rare window into everyday life in the colonial city. They opened up the possibility of writing a history of intimacy, at least from the perspective of the colonial French man.

As I realized the significance of these documents I was shocked at their precarious state. For obvious reasons such as fighting the war and surviving the American bombing, the Vietnamese government had not prioritized preserving these neglected French newspapers from the era of French rule. Despite my delight to read documents that no one had looked at in decades, I was horrified to see the pages crumble as I turned them. When I returned to Hanoi some 15 years later, I found the library had been remodeled and there were now funds to properly store these newspapers. However, this was too late for some of the collection. Many of them were in a serious state of decay, with some of the earlier issues completely unusable or even gone. It was depressing to realize that simply accessing these documents caused damage. The experience made me appreciate just how precious primary sources can be. I bring this experience in the classroom. When I talk with my students about my research we often discuss finding great resources by chance and contemplate how many documents have been lost over the years. This gives my students a better understanding of the historian's craft and instills a reverence for voices from the past, even for dirty cartoons drawn by bored colonizers.

Intimacy Issues: Teaching Histories of Sexuality

Teaching the history of intimacy can be tricky. Beyond assessing the maturity level of our students, issues of historical relevance and the difficulty of finding source material can pose a variety of problems. But these challenges offer teachable moments to delve into discussions of theory and method.

First and foremost, we must make an argument for the significance of the discussion of sexuality. When I teach the subject in my MA level seminar I stress the importance of distinguishing between what is merely titillating and what illustrates larger power structures at work. For example, it is undeniably interesting that Kaiser Wilhelm II had many friends and members of his encourage that engaged in male-on-male sexual practices. Indeed, the contemporary French press loved stories such as the Euelenburg affair which exposed high ranking Prussian officers who systematically preyed upon young military cadets. However, this can be presented as merely gossip and there are real possibilities of homophonic sentiment tainting the discussion. Likewise, mentioning the Kaiser's physical impairments can lead to ableist mockery of the man. But if we situate the scandal in the socio-cultural context of the Second Reich's hyper-masculinity, the sex scandal reveals how heteronormative gender standards drove same-sex behavior underground. The predatory nature of the Euelenburg group further shows how in this authoritarian regime elites could use their power for personal gratification. If we place Wilhelm II's own crisis of masculinity in the historical context of German militarism and its expectations of a leader, we can open new windows into understanding his propensity for elaborate military dress and ritual, vitriolic nationalist speeches, and his reckless foreign policy.4 Perhaps the bull in the china shop was overcompensating for his own perceived short-comings?

Second is the problem of sources. Most of us lead our sex lives in private. By its very definition, the history of intimacy is hidden, shielded from the watchful and judging eyes of the state and its site of official memory, the archive.5 How do we do a history of what happened behind closed doors? How do we observe what historical agents were actively trying to hide? When I was conducting my initial research on the culture of French colonial Hanoi I initially relied on documents in state archives, the "official voice" of empire.6 While the collections in the colonial archives in Aix-en-Provence, France, and the pre-1954 holding in the Vietnamese National Archives contain a wealth of information, it was what the government officials wanted us to know. But what I found was that the colonial state fashioned its own self-image as it curated the archives. Archiving is in and of itself always a political act. In the context of status- conscious regimes, in this case the precarious French Third Republic's newly formed French Indochina, the politicization of image and memory was even more intense. The archiving process involved silencing inconvenient truths that challenged colonial state practices. This made it extremely difficult to find unmediated sources that discussed illicit behavior that transgressed legal and/or moral boundaries. However, when consulting the locally produced newspapers I found a treasure trove of previously unexamined primary sources: cartoons and caricatures of life in the colonial city. Produced by local French residents and published in a French language newspaper at a time when very few Vietnamese could read French, these cartoons were artefacts from conversations within the French community.

Hanoi had a unique urban demography in the 1890s. In this early stage of colonial rule, the French community was much more male and young than in France at the time or in later periods of colonial rule. As Hanoi filled with soldiers and officers, administrative officials from the civil service, and settlers such as merchants, physicians, and other professionals, the white community was roughly 90% to 95% male. Only after 1902 did French women arrive in significant numbers.7 This distorted demography had direct implications for the practice of intimacy. The lack of French women led sexually active French men to look for sexual partners in the Vietnamese and Chinese communities.8 Thus, there was a regular crossing of colonial color-lines. The realities of sexual desire and imperial demographics required transgressing racial boundaries. Colonialism's power relationships ensured that these would be extremely unequal relationships, with prostitution being very common.9

That there were very few white women in Hanoi in the1890s makes these sources even more valuable. Away from the potentially judging eye of French women, these men could engage in more frank discussions about sexual behavior. Things that would have raised shocked eyebrows in communities with a more natural gender balance could be openly discussed. 1890s Hanoi was a boys' club. These white men engaged in what one might call locker-room talk but saw no need to hide it. As the authors did not feel the need to self-censor, these documents articulate voices not heard in the state archives. My source material, the cartoons and poems from the local French press such as La Vie Indo-Chinoise, offer a rare window into the history of inter-racial sex in the city at a moment when there were few reasons to hide intimacy.

Mapping Sexuality in the City

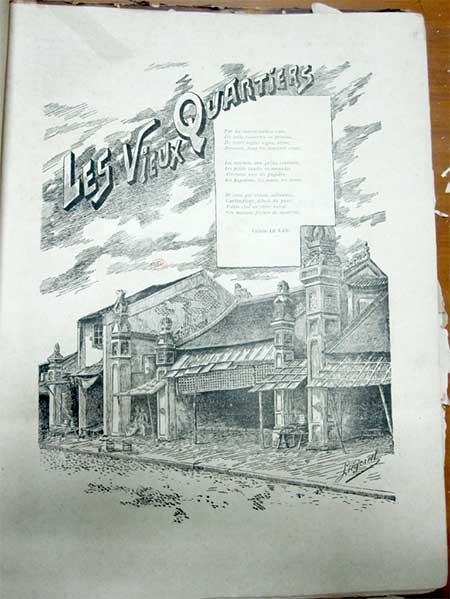

Using these cartoons, we are able to map French male sexual behavior in the colonial city. The sources reveal where the intimate happened. Following colonial urban planning of the era, the French divided Hanoi into quarters.10 Each had a different purpose and population. In the French neighborhood to the south of Ho Hoan Kiem, the beautiful lake at the center of Hanoi, they built wide, straight boulevards lined with trees, spacious villas, department stores, luxurious hotels and restaurants, sidewalk cafés, beaux-arts style office buildings, and even an opera house modelled on its Parisian counterpart. Visitors and residents compared rue Paul Bert, the heart of the European quarter, to a lively street in the metropole. West of the lake were numerous government offices and military barracks. About 5 to 10 percent of the city's population lived in these French controlled sections, which made up about two thirds of the city's space. In the remaining third, the so-called "Old Quarter" or the "36 Streets," lived the majority of the city, the Vietnamese and Chinese. In sharp contrast to the tranquility, space, and wealth of the French quarter, the Old Quarter was densely populated, cramped, and bursting with activity. If there were a few prosperous Chinese merchants, most of the Old Quarter's residents were substantially poorer than the average Frenchman. The shape of the city showed how race and class aligned in the colonial era. Cartoons from the period can be used to teach the material realities of colonial "dual-cities" such as Hanoi.

While the vast majority of white men lived in the French Quarter or the military section of the city, the Sino-Vietnamese Old Quarter was the primary setting for sexual adventures. Out of sight of the colonial state and the potential judgment of white moralizers, the vice industry's brothels and opium dens were in the Old Quarter.11 Framed as exotic, this part of Hanoi became an Orientalist, erotic fantasy-land in the minds of these French men. Using these images as primary sources, students can read them to understand that while colonial racism denigrated the non-white Other, there were aspects of the Other that the colonizer desired, such as exotic ambiances, material luxuries, and subservient bodies. Yet the Old Quarter, home to the numerically superior conquered racial Other, posed dangers to white male bodies. My sources treat such threats in a jocular manner, humorously dismissing sexually transmitted diseases, violent pimps, and even the odd pirate or two. In these cartoons the danger is part of the fun. And the dangers could be jokingly dismissed because the white men knew their dominant status in the colonial power structure. In these illicit adventures, inter-racial sexual encounters were affirmations of white power. They were intimate expressions of white supremacy. Carnal conquests were the personal manifestations of large imperial conquests. France controlled Vietnam and Frenchmen could control Vietnamese women.

These transgressions of the urban color line were not limited to French Hanoi or just colonial cities. We can find similar practices in late Victorian and early 20th century London, New York, and Paris when wealthy white urbanites went "slumming" in the poor and ethnic minority spaces such as Limehouse, Harlem, and the Bal Négre. The Hanoi example can be used to teach the world historical practices of white supremacy.12

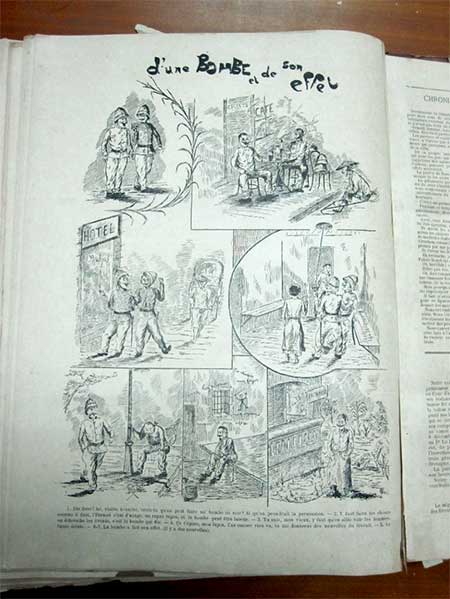

The cartoon "A Wild Night and Its Aftermath" is an excellent source for teaching "slumming" as an exercise in white privilege. The cartoon shows two officers enjoying a bender. They drink in cheap cafés, go to a brothel, and stumble through the Old Quarter's streets. They start in a café drinking a great deal of Pernod before moving on to a seedy brothel. If the night finishes with one stumbling and the other vomiting on the street, the story does not end there. One of them winds up in jail and the other in the infirmary for a sexually transmitted disease.13 The city is a playground, where the white man can drink, carouse, and whoremonger. The flippant cartoon embodies the "boys will be boys" attitude of these sources.

"The Beautiful Girl from Tonkin" literally maps white male sexual desire and practice in Hanoi. Penned by Albert Cézard, who often put himself into his art, this is very accurate representation of the city. Told in the first person, the narrative follows a depressed Baudelairian flâneur strolling French Hanoi. Near Ho Hoan Kiem, the scenic lake in the center of Hanoi that divided the city between colonizer and colonized, he sees a famous courtesan. He enthusiastically follows her out of the safety of the French quarter and into the twisting and disorderly streets of the native quarter. With roofs at odd angles, tarps hanging into the road, and cracked, dilapidated buildings, the sketch revels in the chaos and tumult of urban Vietnamese otherness. To underscore the journey into the exotic, the narrator describes how he offered the woman more and more money as they moved through the various streets. He specifically names the streets, rue des Tasses, rue des Vermicelles en Bambou, rue des Peignes, and rue des Voiles. Ticking off these street names (more correctly hang names), the author places the adventure in an urban geography known to his readers. Composed of thirty-six winding streets, each devoted to the production or trade in a specific product or commodity, the neighborhood stood in stark contrast to the modern and orderly streets of the French quarter.14 The protagonist fails in his conquest and is beaten by a pimp for passing counterfeit coins.15 Cézard gives us an image of the colonial city as offering up pleasure to the white man, provided he can afford it. The city is a site for sexual adventures, but also poses risks and dangers, making it all the more exciting.

Racial Hierarchies of Desire

These cartoons frequently demonstrated a French male hierarchy of desire. White men openly categorized and ranked female sexual partners by their racial origin. Japanese women and Eastern European Jewish prostitutes occupied a privileged space in the minds of these French men. But Japanese and Jewish women also embodied challenges to the maintenance of racial boundaries.

A common genre in La Vie Indo-Chinoise was to compare the various types of female sex workers in the city. The cartoons would take mundane topics such as "small apartments for rent," "priestesses of love," or "how they wake up," and present a two-page spread of images based around the double-entendre. This repeated motif showed that the authors and readers shared a racialized hierarchy of desire in regard to prostitution in colonial Asia. The comparison of sex workers of different ethnicities indicated that these white men shared a set of racial stereotypes, valuing certain alleged racial qualities over others. The cartoons can be used to teach the white colonial male's otherizing gaze.

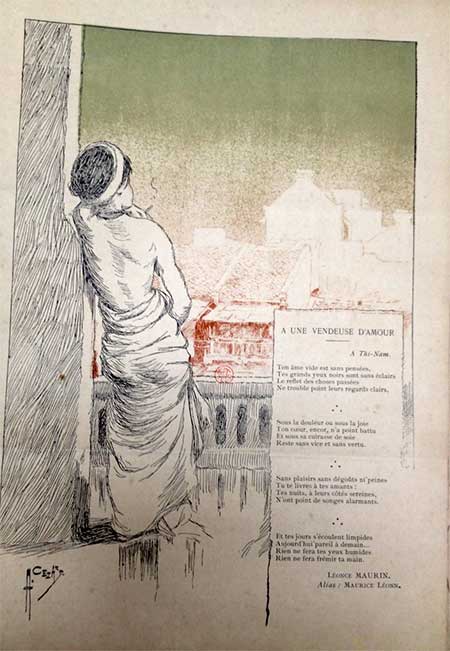

La Vie Indo-Chinoise placed Vietnamese women at the bottom of this hierarchy. Peasants girls from Tonkin (northern Vietnam), often dismissively called by the generic name "Thi-Ba" in the cartoons, were deemed the most plentiful and best price but of the lowest quality. French men made snide remarks about their genderless country attire, the chewing of beetle nut, and the local tradition of women coloring their teeth with black lacquer.16 In contrast, these sources claimed that Saigonese women were much more attractive, sophisticated, and expensive. "Priestesses of Love" noted that they eschewed peasant turbans and lacquered teeth in favor of fine silks and pricey jewelry. The commentary holds that there was fierce competition for these women. The piece also claims that they may actually be from Tonkin villages but adopted the big-city ways associated with the southern capital. The idea that women from Saigon would be more Westernized than their sisters from Tonkin speaks to the longer French presence in the south, as well as Vietnam's cultural divide between a rigid Confucian north and a flexible Buddhist south.17 To this very day, Northern Vietnamese retain the reputation for being much more conservative, traditional, and reserved than their freewheeling, syncretic, and gregarious neighbors to the south. The predatory colonial man translated this cultural knowledge into an assessment of sexual availability and sophistication. According to La Vie Indo-Chinoise, Saigonese prostitutes were skilled practitioners of the trade.18 The cartoons territorialize male sexual desire within France's colonial possessions. According to Cézard's "Small Apartments for Rent," Vietnamese women posed greater health risks as they had more "tenants." The piece jokes about frequent visits from the health inspector, a reference to the requirement of registered prostitutes to submit to regular checks for sexually transmitted diseases.19

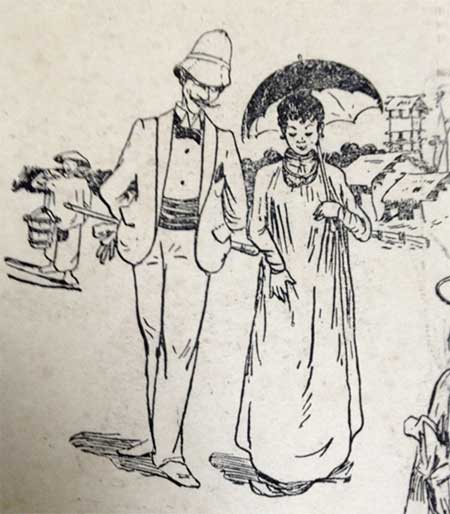

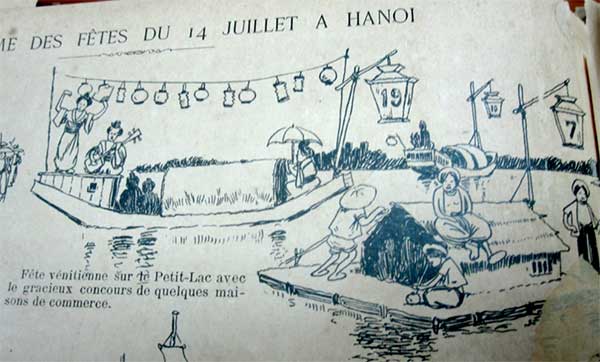

In the comparative cartoons and in numerous other pieces, Japanese sex workers received prominent attention. Organized crime networks trafficking sex-workers known as karayuki-san operated throughout the major cities of Asia.20 These women were not street walkers. Indeed, they worked in discrete high-end brothels. When in public they wore their hair up in buns and dressed in distinctive Japanese attire including cotton kimonos, wide obi belts, and geta, wooden raised sandals.21 The images in La Vie Indo-Chinoise indicate that French men, like many white men around the world, fetishized Japanese clothing as a central aspect of their Orientalist desire. The sketches present the women as clean, well dressed, and calm. They were always dignified and beautiful models of perfection that stand in contrast to the Vietnamese women and their peasant ways.22 Frequently, images depict them playing traditional musical instruments or kneeling in submissive poses before their clients. The text accompanying these cartoons assures the readers that the Japanese sex workers are healthier and more sophisticated than the local competitors and thus more expensive. Japanese sex workers had a global reputation for high quality, which could translate into substantial profits.23 The author of "Priestesses of Love" stressed their personal hygiene as central to their value and other pieces noted that the Japanese brothels were well lit and clean. French men referred to karayuki-san by the slang term "Madame Chrysanthemum," underlining their low-brow Orientalist appeal.24

French male lust for Japanese women demonstrated a regional territorialization of desire. In addition to fetishizing the Karayuki-san, travel to Japan was an obsession. In "Nippon Jorôya!" ("Japan Brothel!") Victor Le Lan ponders the erotic sophistication of Japanese women and expresses his enthusiasm about visiting Japan.25 While specifically speaking of Japan as a destination for sex tourism, his verses generalize all Japanese women as erotic and available. The poem is accompanied by a large cartoon of rather amateurish quality showing two Japanese women in stereotypically traditional attire. Another image shows a seductive Japanese woman looking at the viewer with her head slightly bowed with the caption "In Japan. A moment of well-deserved rest."26 These pieces refer to important imperial phenomena in the 1890s. Prior to the establishment of Indochinese hill stations, French civil servants were sent to Yokohama for rest and recuperation. Colonial medical consensus held that European bodies were unsuited for tropical heat and humidity and temperate Japan would restore them (and was cheaper than sending men back to France).27 However, this came to an end after 1900. With Governor General Paul Doumer's decision to build a hill station in Dalat in Southern Vietnam, French men lost an excuse to indulge in erotic adventures in Japan (this was one of many decisions that made the authoritarian Doumer unpopular). Meanwhile, the Japanese government was increasingly embarrassed about its reputation as a sex tourism destination.28 With the Japanese victory in the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905), the French suddenly saw Japan as a serious imperial and references to Japan as a destination for sexual fantasy disappeared.

On the Margins of Whiteness

The term "Valaque" often appeared in La Vie Indo-Chinoise. The word translates as "Wallachian," a reference to present day Romania, but meant Eastern European Jewish sex-workers. These women fled poverty, late nineteenth century pogroms, and other forms of anti-Semitism, only to be caught up in global crime networks. The traffic in Ashkenazi women was not limited to French Indochina, as they were a well-known group in Bombay, Singapore, and Hong Kong.29 Due to their white skin, these women frequently enjoyed a higher status than their Asian competitors and might specialize in serving a "clientele [that] included French military officers, civil servants, and rich merchants."30 In a book published in Saigon in 1913, André Joyeux depicted a scene with a French man getting dressed and a dark haired European woman on a bed with the caption, "she only spoke Romanian but she reminded of France nonetheless."31 While Asian prostitutes were plentiful in Hanoi, colonial demographics created market demand for European women. In the numerous two-page illustrations of different types of prostitutes, the authors of La Vie Indo-Chinoise always included a discussion of Valaques and generally spoke of them with praise. Valaques were able to use their fetishized status to their own advantage. The administration set up privileged regulations for them, including the right to sell alcohol in their cafés, a special European-only section of the dispensary for private medical exams, and the right to receive customers in private apartments.32

However, Valaques raised complicated issues for the colonial state and the wags of La Vie Indo-Chinoise. Despite the privilege of their white skin, these women were associated with international crime networks and pimps who moved them through the port cities of South America, South Africa, and colonial Asia. In addition to smuggling women, they also moved bootleg alcohol, circumventing colonial taxation. Sometimes this black-market booze was spoiled or even dangerous. Even though human traffickers exploited these women, the French men of Hanoi viewed them as guilty by association. Hanoi's French men prized their white bodies but despised them as a threat to public health and the law. As many men brought France's rabid anti-Semitism with them, their Jewishness was cause for further vilification.

Occupying the colony's racial margins, the Valaques called attention to the uncertain boundaries between white and non-white. They posed a paradoxical challenge to the colonial order of things. In a setting where whiteness was essential for establishing privilege, these poor, Jewish, Eastern European sex workers tarnished the idea of white prestige. Such troubling ambiguities eventually led to their expulsion after 1907.33

Conclusion

The sources in my Journal of World History article can be used to teach several aspects of colonial culture in the era of the New Imperialism. The cartoons illustrate both the racial divisions of colonial dual cities but also the ways in which white men crossed the color-line to fulfill their sexual desires; a practice not limited to the empire by any means. These sources demonstrate the ways in which colonial racism classified people, in this case women, based upon racial stereotypes and assigned generalized traits to each group. The representation of Jewish sex-workers reveals the inherently unstable nature of racial categories, including the necessity of policing whiteness. These documents further allow us to teach the ways in which histories of intimacy can escape the archival record. Teaching history through these cartoons offers opportunities for students to consider where historical sources come from. Thus, we can teach both content and historical method with these images.

Appendix One: Discussion questions

1) What do these cartoons tell us that official government documents might not?

2) How do these cartoons illustrate racial hierarchies on colonial Vietnam?

3) How was colonial Hanoi a "dual city?"

4) How do we understand the conflict between colonial era racism and colonial male sexual desire for Asian women? Is there a conflict?

5) Do you think inter-racial sex challenged or reinforced racial boundaries and hierarchies?

6) What role did Jewish prostitutes play in the colonial racial hierarchies?

7) How do these sources compare with contemporary sex tourism in Southeast Asia?

Appendix Two: Sources

|

|||

| Figure 2: The colonial city as site of racial domination and sexual opportunity for the privileged white man. La Vie Indo-Chinoise, "Escrarbilles," La Vie Indo-Chinoise, February 26, 1898. | |||

|

|||

| Figure 3: Not unlike Thailand today, turn-of-the-century Japan had a well-known, and embarrassing, reputation as a site of sex tourism. "In Japan. A moment of well-earned rest." La Vie Indo-Chinoise, March 26, 1897. | |||

|

|||

| Figure 4: The masthead of André Cézard's weekly La Vie Indo-Chinoise embodied the paper's bon vivant and libertine self-image but can be read as an affirmation of colonial white male supremacy, a world view based upon an image of the empire as a source sexually available women and subservient "natives." | |||

|

|||

| Figure 5: "Program for July 14th Celebrations in Hanoi" La Vie-Indochinoise,

July 3, 1897. "Venetian party on the Small Lake [Ho Hoan Kiem] with the gracious participation of several commercial enterprises." The cartoon suggests brothels were part of the annual Bastille Day celebrations. Note the contrast between the high end Japanese establishment (#19) and the more modest Vietnamese competitor (#7). |

|||

|

|||

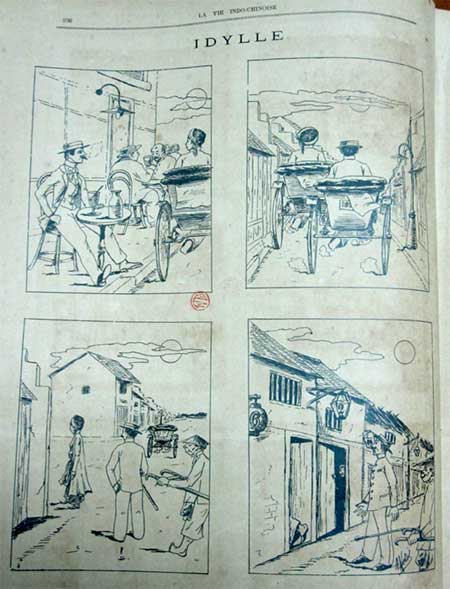

| Figure 6: The white colonial man, an imperial flâneur, spots an object of sexual desire in "Idyll," La Vie Indo-Chinoise, July 31, 1897. | |||

|

|||

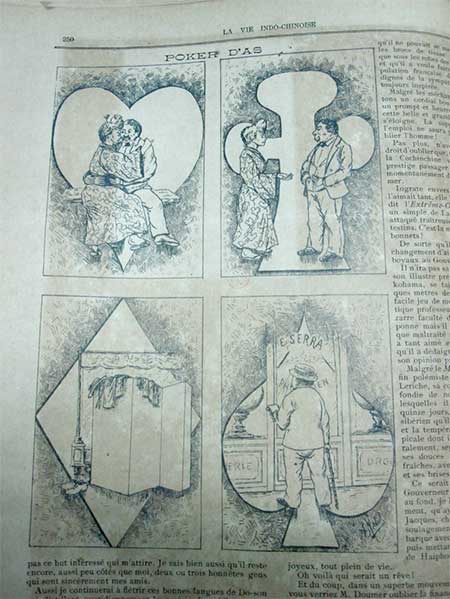

| Figure 7: A Frenchman visits a high end Japanese courtesan and then a well-known Hanoi pharmacy in "The Ace of Spades," La Vie Indo-Chinoise, August 14, 1897. | |||

|

|||

| Figure 8: Sexuality opportunity and perils awaited white men who ventured into Old Quarter. "The Bender and Its Impact" shows two white men drinking and visiting brothels in Hanoi with unfortunate consequences. "D'Une bombe et de son effet," La Vie Indo-Chinoise, December, 1897. | |||

|

|||

Figure 9: Victor Le Lan, "The Old Quarters" in La Vie Indochinoise, February 5, 1898

|

|||

Michael Vann is Professor of History at Sacramento State University (mikevann@csus.edu)

1 Michael G. Vann, "Sex and the Colonial City: Mapping Masculinity, Whiteness, and Desire in French Occupied Hanoi," Journal of World History, Volume 28, Numbers 3 & 4, December 2017, pp. 395–435.

2 Louis Bonnafort, "Préface," in Soyons Sérieux!, ed. Alfred Cézard (Hanoi: Schneider, 1904).

3 Alain Corbin, Women for Hire: Prostitution and Sexuality in France after 1850 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990) and Judith R. Walkowitz, City of Dreadful Delight: Narratives of Sexual Danger in Late-Victorian London (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1992) are foundational studies of white male predatory culture in Europe.

4 Norman Domeier, The Eulenburg Affair: A Cultural History of Politics in the German Empire, (Rochester: Boydell & Brewer, 2015), Heike I. Schmidt, "Colonial Intimacy: The Rechenberg Scandal and Homosexuality in German East Africa," Journal of the History of Sexuality 17, no. 1 (2008), and Michael G. Vann, "Caricaturing 'the colonial good life' in French Indochina," European Comic Art 1, no. 2 (2009).

5 Ann Laura Stoler, Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009) and Anjali Arondekar, For the Record: On Sexuality and the Colonial Archive in India (Durham: Duke University Press, 2009).

6 Vietnam National Archives 1 (hereafter VNA) Maire de Hanoi (hereafter MdH) 2574 "Réglemetation sur la prostitution et les debits de boissons dans la ville de Hanoi. 1888–1916" and VNA 1 MdH 2579 "Traitement des femmes publiques au dispensairs municipale de Hanoi. 5.9.1895 – 29.6.1936."

7 VNA 1 MdH 3214 "Table alphabétique des mariages européens de la Villa de Hanoi. 1886–1900."

8 Vu Trong Phung (Author), Shaun Kingsley Malarney (Translator), Luc Xi: Prostitution and Venereal Disease in Colonial Hanoi (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2010).

9 Dr. Bernard Joyeux, "Le Péril vénérien et la prostitution à Hanoi," Bulletin de la Société Médico-Chirurgicale de l'Indochine (June 1930): 616–617.

10 Michael G. Vann, "Building Whiteness on the Red River: Race, Power, and Urbanism in Paul Doumer's Hanoi, 1897–1902," Historical Reflections/Réflections Historique (2007).

11 VNA 1 MdH 2580 "Rapport fait par le commisaire de Police de Hanoi sur la repression de la prostitution clandestine et la salubrité des maisons de Tolérance de cette ville. 7. 1896," P.B., Le Rôle et la Situation de la Famille Française dans nos Colonies (Paris: Journal des Colonaiux & L'Armée Coloniale Réunis, 1927), 7–8 and Centre Des Archives Section d'Outre-Mer (hereafter CAOM), Affaires Politiques, carton 2417, dossier 4: "Rapport présenté par M. Hardouin, Consul général en mission, au nom de la Commission chargée d'examiner la question de l'Opium en Indo-Chine" (1907).

12 Chad Heap, Slumming: Sexual and Racial Encounters in American Nightlife, 1885–1940 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010), Robert M. Dowling, Slumming in New York: From the Water Front to Mythic Harlem (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2007), Seth Koven, Slumming: Sexual and Social Politics in Victorian London (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007), and Anne Victoria Witchard, Thomas Burke's Dark Chinoiserie: Limehouse Nights and the Queer Spell of Chinatown (Farham: Ashgate, 2009).

13 "D'Une bombe et de son effet," La Vie Indo-Chinoise (hereafter LVI-C), December, 1897.

14 Michael G. Vann, "Building Whiteness on the Red River: Race, Power, and Urbanism in Paul Doumer's Hanoi, 1897–1902," Historical Reflections/Réflections Historique (2007).

15 "La Jolie Tonkinoise," LVI-C, March, 1898.

16 Paul Lechesne, Notions Lointaines: Indo-Chine: Reflexions (1905), Acualités (1906), Possibilités Économiques (1906/1907) (Paris: La Librarie Mondiale, 1907), 53, Osbourne, Fear and Fascination, and Christiane Fournier, Perspectives occidentales sur l'Indochine (Saigon, La Nouvelle Revue Indochinoise: 1935): 90, 94, and 102–106.

17 Neil L. Jameson, Understanding Vietnam (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993).

18 "Prêtresses d'Amour," LVI-C, November 28, 1896.

19 "Petits Apartments à Louer," LVI-C, March 12, 1898.

20 James F. Warren, Ah Ku and Karayuki-San: Prostitution in Singapore 1880–1940 (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 1992) is the classic work on the subject. Mark Driscoll, Absolute Erotic, Absolute Grotesque: The Living, Dead, and Undead in Japan's Imperialism, 1895–1945 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010) argues that sex trafficking by the yakuza was an imperial strategy consciously designed to infiltrate the existing European colonial empires in Southeast Asia.

21 Dr. Paul Roux, "La prostituée japonaise au Tonkin," in Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d'anthropologie de Paris, vol. 6 (1905), 203–210.

22 "Moeurs Japonais," LVI-C, February 13, 1897 and "Procureuse," LVI-C, February 20, 1897.

23 For Japanese women who made small fortunes in Seattle and then returned home to build impressive homes, see Rizzo and Gerontakis, Intimate Empires, 79.

24 Pierre Loti, Madame Chrysanthème (Paris: Calmann Lévy, 1888).

25 "Nippon Jorôya!" LVI-C, January 29, 1898.

26 "Au Japon," LVI-C, March 26, 1898.

27 Eric Jennings, Imperial Heights: Dalat and the Making and Undoing of French Indochina (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 11–12 and 20. See Warwick Anderson, Colonial Pathologies: American Tropical Medicine, Race, and Hygiene in the Philippines (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006), 130–157, for the ways in which Euro-American male bodies were deemed vulnerable in the dangerous Southeast Asian climate.

28 Yorimitsu Hashimoto, "Japanese Tea Party Representations of Victorian Paradise and Playground in The Geisha (1896)," in Histories of Tourism: Representation, Identity and Conflict, ed. John K. Walton (Toronto: Channel View Publications, 2005): 120.

29 Philippa Levine, Prostitution, Race, and Politics: Policing Venereal Disease in the British Empire (New York: Routledge, 2003), 223–227 and Warren, Ah Ku and Karayuki-San, 75–76.

30 Nicolas Lainez, "Human Trade in Colonial Vietnam," in Wind Over Water: Migration in an East Asian Context, eds. David W. Haines, Keiko Yamanaka, and Shinji Yamashita (New York: Berghahn, 2012), 26.

31 Michael G. Vann, "The Colonial Good Life:" A Commentary on André Joyeux's Vision of French Indochina (Bangkok: White Lotus, 2008).

32 VNA 1 MdH 2574 "Réglemetation sur la prostitution et les debits de boissons dans la ville de Hanoi. 1888–1916."

33 VNA 1 RST 076427-03: "Expulsions de l'Indochine des Européens étrangers en 1906–1908."