Nineteenth-Century Constitutions: A Teaching Guide

Joanna Neilson

A successful world history course asks students to think critically about ideas, situations, people, and events from a broad range of cultures and times. Inspired by a chapter in Weisner-Hanks et al's textbook, Discovering the Global Past on states trying to use constitutional reform to ward off imperial encroachment, I present my students with several nineteenth-century constitutions from a variety of countries that all sought to give new states a solid political foundation or to strengthen existing states from within. 1 In the resulting assignment, I ask students to think differently about the nineteenth century by using ways of discussing the Atlantic Revolutions (1688–1815) and applying them to a later period and other parts of the world. Imperialism and nationalism still play parts in the story told from this perspective, but the assignment guides students to consider many geographic areas that rarely appear in our customary narrative as well as viewing European and North American history in new ways. This article will discuss the assignment, examine other approaches to using this document collection, and assess the major themes that this project illustrates for students.

For this project, students examine one or more constitutions, discuss assigned questions about the governments where they emerged, and make some larger comparisons among the constitutions. In the past few years, I have used two variations of the assignment. In my online "World History since 1500" course, students participate in weekly discussion group discussions where each group has the same prompts and document choices. For this class, each student chooses a constitution and writes a post analyzing the constitution based on the prompts provided. Later in the week, students step back and make some larger comparisons from among the constitutions discussed. Students in the "Honors World History since 1500" (a traditional lecture class) chose three constitutions and write a comparison paper using the same prompt questions as the online class.

Two initial criteria determined the selection process for this project: date and availability in English. In the period after the major Atlantic Revolutions, I started the date range with 1830 to roughly the turn of the twentieth century. Many of the nineteenth-century constitutions are available on World Constitutions Illustrated from HeinOnline, a collection that had been freely accessible at the Comparative Constitutions Project (now https://www.constituteproject.org/) when I started this project but is now a subscription-only database. Although this academic database provides many of the documents for the project, I also used the Internet Modern History Sourcebook [https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/mod/modsbook.asp], the Hanover Historical Text Project [https://history.hanover.edu/project.php], Google Books [https://books.google.com], and several other collections. The list below includes constitutions that I have identified since teaching this assignment.

Table 1 Selected Constitutions, 1830–1905

Country and Year |

Citation Information |

Ecuador 1830 |

"Constitution of the Republic of Ecuador, September 23, 1830." World Constitutions Illustrated. HeinOnline. Last accessed September 11, 2018. |

France, 1830 |

"The French Constitution of 1830." Internet Modern History Sourcebook. Last accessed September 03, 2018. https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/mod/1830frenchconstitution.asp. |

Uruguay 1830 |

"Constitution of the Republic of Uruguay, June 28, 1830." World Constitutions Illustrated. HeinOnline. Last accessed September 11, 2018. |

Belgium 1831 |

"The Constitution of the Kingdom of Belgium." World Constitutions Illustrated. HeinOnline. Last accessed 02 October 2018. |

Great Britain, 1832 |

Great Reform Act of 1832. The Great Reform Act of 1832 works as a comparison piece and not a constitution-style document on its own because I have not found a transcription of the Act beyond the opening paragraph. However, giving students a good summary of the act should provide them with enough material for making comparisons. |

Spain, 1837 |

"Constitution of the Spanish Monarchy, June 18, 1837." World Constitutions Illustrated. HeinOnline. Last accessed September 11, 2018. |

El Salvador 1841 |

"Constitution of El Salvador, 1841." World Constitutions Illustrated. HeinOnline. Last accessed September 11, 2018. |

Liberia 1847 |

"Constitution of the Republic of Liberia." 1847. World Constitutions Illustrated. HeinOnline. Last accessed September 11, 2018. |

France, 1848 |

"Constitution of the French Republic. Adopted November, 1848." In Francis Lieber, On Civil Liberty and Self Government. Ed by Theodore D. Woolsey. 3rd ed revised. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1883. Online Library of Liberty. Last accessed October 01, 2018. Http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/lieber-on-civil-liberty-and-self-government. |

Argentina, 1860 |

"Constitution of the Federal Republic of Argentina. September 25th, 1860." World Constitutions Illustrated. HeinOnline. Last accessed September 11, 2018. |

Tunisia, 1861 |

Gress, Maria del Carmen, trans. Organic Law or Political and Administrative Code of the Tunisian Kingdom (Apr. 26, 1861). HeinOnline World Constitutions Illustrated Library 2014. Last accessed September 13, 2018. |

Kingdom of Hawai'i 1864 |

"Kingdom of Hawai'i Constitution of 1864." Hawaii-Nation.org. Last accessed September 11, 2018. https://www.hawaii-nation.org/constitution-1864.html. |

United States of America, 1865, 1868, 1870. |

"Amendments 13, 14, and 15. Constitution of the United States." Government Publishing Office. Last accessed September 03, 2018. Http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/GPO-CONAN-1992/pdf/GPO-CONAN-1992-7.pdf. |

The Austrian Empire, 1867 |

"Austrian Constitution of 1867: Fundamental Law Concerning the General Rights of Citizens." Cornell University Ecommons. Last accessed September 03, 2018. Https://ecommons.cornell.edu/handle/1813/1443. |

Paraguay, 1870 |

"Constitution of the Republic of Paraguay, November 24, 1870." World Constitutions Illustrated. HeinOnline. Last accessed September 11, 2018. |

New Fante Confederacy, 1871 |

"Constitution of the New Fante Confederacy." Modern Ghana News. Last accessed September 03, 2018. Http://www.modernghana.com/news/123177/1/constitution-of-the-new-fante-confederacy.html. |

The Ottoman Empire, 1876 |

"The Ottoman Constitution, Promulgated the 7th Zilbridje, 1293 (11/23 December, 1876)." The American Journal of International Law 2.4 Supplement: Official Documents (October 1908): 367–387. DOI: 10.2307/2212668. Last accessed September 11, 2018. "The Ottoman Constitution." Last accessed September 03, 2018. http://www.anayasa.gen.tr/1876constitution.htm. |

Japan, 1889 |

"The Constitution of the Empire of Japan." From Hirobumi Ito, Commentaries on the Constitution of the Empire of Japan. Translated by Miyoji Ito. Tokyo: Igirisu-horitsu gaako, 1889. Hanover Historical Text Project. Last accessed September 03, 2018. http://history.hanover.edu/texts/1889con.html. |

Brazil, 1889 |

Wallace, Elizabeth, ed. The Constitution of the Argentine Republic. The Constitution of the United States of Brazil. Chicago: University Press of Chicago, 1894. Free e-book from GoogleBooks. |

The Qajar Empire (Persia), 1905 |

"The Farman (Royal Proclamation) of August 5, 1906." Human Rights and Democracy for Iran. Last accessed September 03, 2018. Http://www.iranrights.org/english/document-91.php. "The Fundamental Laws of Persia." Human Rights and Democracy for Iran. Last accessed September 03, 2018. Http://www.iranrights.org/english/document-204.php. "The Supplementary Fundamental Laws of Persia." Human Rights and Democracy for Iran. Last accessed September 03, 2018. Http://www.iranrights.org/english/document-205.php. |

Nicaragua, 1905 |

"Constitution of the Republic of Nicaragua, March 30th, 1905." World Constitutions Illustrated. HeinOnline. Last accessed September 11, 2018. |

In general, the constitutions included in this project resulted from one of the following situations. The first group includes states attempting to organize themselves along western lines against possible western intrusion such as Hawai'i and the Fante Confederation. The second group includes new states built from the remains of Napoleon's empire such as Belgium, new states that gained their independence from a colonial power such as Liberia and Uruguay, and states that broke away from previous political alliances, such as Ecuador and El Salvador. Third, many states used constitutions to strengthen (or appear to strengthen) themselves from within. This political action took two forms: first, states rebuilding from internal crises, including France, Argentina, the United States of America, Brazil, and Nicaragua, and second, monarchies that wanted to use a constitution to solidify their power, including the Spanish, the Austrians, the Ottomans, the Qajar, and the Meiji. Great Britain is an outlier here because its constitutional changes resulted from the normal political processes.

As students discuss these constitutions, they should provide evidence-based answers to the following questions:

1. How does each constitution define the role of the individual in its society? What role does the individual play in government?

2. Who has the most power in these constitutions? (This question can have two approaches – the location of sovereignty and the actual exercise of power.)

3. Which of these constitutions appears to be the strongest and why? (This question asks them to take their comparisons further, as they have to define what they think makes a country strong by contemporary standards before they can assess the strength of the constitutions.)

With each question, I require students to exercise evaluative and taxonomic analysis. Students begin their investigation by focusing on how the constitutions' architects defined the role of individuals in these systems. Do the authors describe individuals as citizens or subjects, and, is this distinction meaningful for each society? Certainly, using the term "subject" implies an over-arching monarchical vision of the state and loyalty to an individual or family more than the term "citizen" does. However, this difference may be unimportant if the sense of the document calls people citizens but treats them as subjects.

As students consider how and where individuals figure into these constitutions, they quickly realize they must determine who each constitution defined a citizen or subject. Students see how social status, economic standing, ethnicity, and gender played important parts in these definitions because some architects explicitly rejected one or more of those categories to define citizenship. The most obvious example of this redefinition was the constitutional changes after the United States Civil War, where the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments specifically stated that race could not be used to exclude citizens from active participation in government.2 Some constitutions, such as those of Argentina, Brazil, and Tunisia, also explicitly defined citizens and resident aliens, indicating that these states saw the value of non-citizens to their communities. Framers laid out foreigners' rights and responsibilities and promised these residents that the government would not force them to become citizens to stay in the country. Paraguay also actively encouraged European and US immigration.3

Some of these constitutions provide detailed discussions of the requirements for and obligations of citizenship. For example, the authors of the French 1848 constitution began the document with a discussion of citizens' responsibilities to the Republic and the Republic's obligations to the people. The authors then affirmed universal manhood suffrage and specifically reject any property requirement for voting eligibility. With their independence from Brazil in 1828, Uruguayan builders laid out citizenship for all males over twenty but also explained that citizens could have their citizenship rights suspended for a variety of reasons including "being a drunkard," i.e. morally unfit in a nation whose constitution declared Roman Catholicism as the national faith. Nicaraguan political leaders established many rights for citizens, including the right to vote, to hold public office, and to own firearms. However, these "rights of citizenship" did not extend to all men; convicted criminals and people of diminished mental capacity could not participate as other Nicaraguans could.4

|

|||

| Figure 1: Blanes, Boceto para Jura de la Constitución de 1830. Uruguay. Source: Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Boceto_para_la_Jura_de_la_Constituci%C3%B3n_de_1830.jpg. | |||

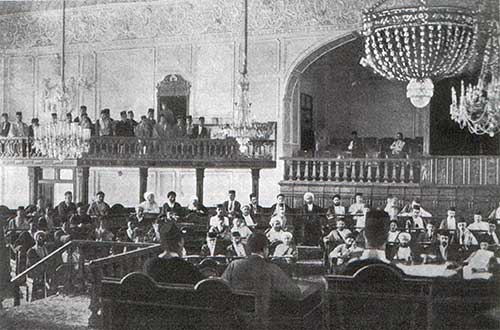

Although focusing on the role of the individual may project modern political understandings into the past too much, using this approach has immediate roots in the Enlightenment and Atlantic Revolutions and guides students to investigate how the constitutions' authors assigned representation in their central legislature. Almost all constitutions in this set provided for some kind of semi-representative bodies as a part of the government, but sometimes the new bodies explicitly represented only the political and well-connected classes. Students consider if the authors assigned representation based on older social models, outdated population statistics, or perceived value to the central government or if the authors reformed older ways, calling for a fresh assessment of the social and population distribution as the new basis for assigning representation. In the Qajar documents, the authors established a National Consultative Assembly with representatives elected from across the empire, but gave the Tehran representatives more influence in the government, saying that capital members did not have to wait for the provincial members to assemble before conducting business.5

|

|||

| Figure 2: Parliament Tehran, 1906. Source: Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Parliamenttehran1906.jpg. | |||

After situating the individual in these various constitutional frameworks, and determining the make-up of the representative bodies, students step back and examine power-sharing among representative bodies and other ruling agents in these constitutions. This question asks students to think about who had the power to make law. Students could consider what issues the legislature had the legal right to discuss, what group or groups proposed legislation, and whose approval of the proposed legislation was required to make the legislation into law.

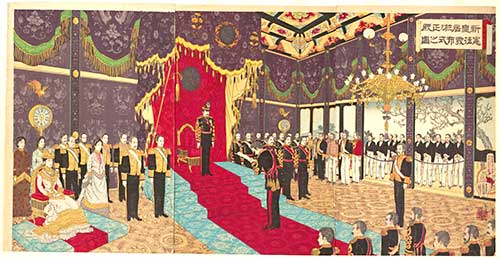

One useful approach to answering this part of the prompt involves understanding what groups in society benefitted from the constitutional provisions. Constitutions that gave every man equal citizenship benefitted groups that had been excluded before, such as non-Muslims in the Ottoman and Tunisian constitutions and African-Americans in the United States.6 Applying this benefit analysis approach to the monarchies represented in this set, students encounter situations where rulers sought to use the form of the constitution to codify their own position as the location of sovereignty while pretending to negotiate a political settlement with their people without really giving up any substantial power. This octroi, octroyed, or granted constitutional model had its origins in the early nineteenth-century European monarchies rebuilding after the Napoleonic empire. However, as Jörg Gerkrath points out, this model fits situations and constitutions from other parts of the world, such as the Ottoman Empire and the Meiji Restoration in Japan, not just situations found in European states.7

|

|||

| Figure 3: Adachi Ginkō, View of the Issuance of the State Constitution in the State Chamber of the New Imperial Palace, 1889. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art. CCO 1.0. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/55246 (listed as in the Public Domain). | |||

The last part of the prompt requires students to make an argument based on the criteria they think are valid for assessing the strength of a state and constitution, balanced against their understanding that historians should not assess the past based on twenty-first-century ideas of liberty or styles of government. Some students might choose to define strongest based on protections of individual liberties. Others could argue that strongest meant providing the best command structure and overall plan for the integrity and smooth operation of the state. Students might also try to argue strength from later development, for example, saying the Meiji constitution was the strongest because the Japanese strengthened their state and prospered, while the Ottomans transformed into Turkey, and the Qajars fell to the Pahlavi dynasty. For Hawai'i and the New Fante Confederation, who both eventually lost their independence to the United States and the British Empire respectively, students must consider what role if any constitutional development played in keeping these two states independent. However, students may argue that these two areas were stronger after they became parts of larger empires.

Possible Assignment Variations

This set of documents can be used in several ways to complement a high school, Advanced Placement World History, or college course. Instructors can ask students to make a full analysis of one constitution where the student provides the background context, analyzes the constitution, and then assesses the impacts of the political action on the country. A quick comparison paper could assign students one of the prompt questions and two or three constitutions. These documents can be grouped in multiple ways: by geographic region, by time, by reasons for the constitutions, by authorship, by the type of government declared, or by who benefitted the most from constitutional protection. Students could present their results as papers or group wikis for written work, or presentations or panel discussions in class.

Shifting the focus somewhat, instructors could use many documents in this set to talk about how political groups built new states in this period. This sub-set category includes constitutions from states that became independent under varying circumstances: newly-established or reestablished European states resulting from European war (Belgium 1831), independence from a former western colonial power (Liberia from the United States in 1847 or Uruguay from Brazil in 1828), and states separating into smaller units (Ecuador from Gran Colombia in 1830 and El Salvador from the Federal Republic of Central America in 1839). This assignment would be another compare and contrast exercise and could highlight similarities and differences in influences, processes, and cultures.

The approach and prompts discussed here can be applied to several other periods in world history. Classes could examine the constitutions of mid-twentieth century decolonized Asian and African states. Students could also use the prompt to investigate the changes in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union in the 1990s. Instead of only discussing how states came to be, classes could also examine how other states broke apart in the late twentieth and early twentieth centuries such as Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, or Sudan. Many constitutions for states in these groups can be found in English for free online at the Constitute Project.8

Instructors interested in broader chronological comparisons could use this approach to compare states and constitutions from more than one period defined above. For the Atlantic World revolutions, students could look for direct influences from the United States and French documents on the later constitutional movements. George Billias' American Constitutionalism Heard Round the World, 1776–1989: A Global Perspective is a good place to start for instructor background.9 For a more creative approach, teachers could ask students to suspend their disbelief and create fictionalized communications between people working on these different constitutions, either all from the same time-period or across two or more. Students could choose to have people who might agree or disagree on the proper role of the individual or the location of power in government talk to each other or write letters. Characters from the older period could write to someone from the later period to offer advice, congratulations, or complaints about how the younger people got it wrong. Assessment can be based on how the student demonstrates he or she understands the constitutions of each correspondent they create.

Overall Conclusions

Asking students to make this broad survey and assessment of multiple constitutions allows instructors to illustrate several underlying themes in world history and provides students with the primary sources to trace these ideas for themselves. First, this assignment demonstrates how multiple states in the nineteenth century were in flux, how uncertainty was not just a colonial phenomenon, and how these situations fit into their larger global context. This flux had a few common themes, such as economic instability and nationalism. Second, this project demonstrates that a constitution does not automatically signal democracy, significant power-sharing, or progress toward a twenty-first-century style government. A "constitution" has not always meant what we seem to invest in it today. I develop this subtheme throughout the course, especially during our discussions of the Revolutionary Atlantic, when I stress the worldview of those creating the new North and South American states – protecting their group and securing their place, not empowering everyone who lived in these states. The Constitution of the New Fante Confederacy represents an extreme example of the few using a constitution to protect the rights and place of those few against the many. Concerned about their British imperial neighbors, several leaders of the Fante people established this constitution to demonstrate to the British that the Fante did not need British administration. This constitution does not focus on the rights and responsibilities of the people; rather it defines the rights of the Fante leaders who sought to reinforce their positions as the legitimate governors of the area.10 Other constitutions in this set used the bicameral legislature but did not make both houses elected, giving more protection to those building the new frameworks. In the Ottoman, Meiji, and Qajar visions, the governments determined the membership of the upper house, limiting access to members of the royal family and chosen allies. Other constitutions such as Argentina and Brazil provided for an elected House of Deputies or Representatives and a state legislature-appointed Senate.11 These situations should help demonstrate to students that we cannot expect to see the same constitutional values of today in documents and situations of a different period.

Third, students should become increasingly aware that over time, societies' ideas of who has the right to participate in government, who constitutes the political classes with a legitimate and recognized voice in government affairs, have changed slowly over time. The United States and Great Britain offer the starkest examples of this phenomenon, as their constitutional changes during the nineteenth century enfranchised, on paper at least, significant portions of their populations.

Fourth, the breadth of this assignment spotlights areas of the world that may not receive much attention in a world history survey course and provide new ways to examine other areas usually discussed in different contexts. Spain, for example, may recede into the background for many world history instructors after the end of Napoléon's empire and the successful Latin American Wars of Independence. The 1837 Constitution can show how the Spanish government regrouped, what parts of their past they choose to maintain, and what new ideas political leaders wanted to incorporate into their restored state.12

Anecdotal evidence suggests that students may need more guidance with this assignment than I have provided in the past. One student in a brick-and-mortar class commented that the reading was a little hard going because the documents they chose were are similar. Throughout my discussion above, I have included other ideas that could help student approach the prompts and I am considering incorporating some of them in the future. I have had better success with the online discussion group discussion of this assignment and can envision a way to translate part of this approach to a brick-and-mortar class. After choosing several constitutions, I would assign several students the same constitution. Each person would assess his or her own constitution and provide a short written document analysis. Then, after the students have submitted their analyses in the next class meeting, we would have the comparison part of the assignment as an in-class discussion. I would choose several of the features for us to discuss and start by asking the class to address those characteristics using their own constitutions. Because more than one person analyzes each constitution, there would be multiple voices to answer for each document. As the students answer the questions, I would create a chart on the projected computer screen to show the compare and contrast. At this point, instructors could split the class into multiple small groups and task them with creating a comparison using one of the categories that I have listed on the screen. They do not need to write out the comparison, just define the thesis or topic sentence and list the salient points. Instructors could assign the same part of the exercise to each student individually, either as in-class work or homework. Instructors could assess the single constitution analysis, the class participation, and the resulting comparison exercise. At the end of the assignment, students should have a better understanding of the world history themes discussed in this article and guided practice with primary source close reading, comparison analysis, and argument construction.

Joanna Neilson is an Assistant Professor of History and Chair of the Humanities Department at Lincoln Memorial University. She can be reached at joanna.neilson@lmunet.edu.

1 See Weisner et al., Discovering the Global Past, vol II (Boston: Wadsworth / Cengage Learning, 2012), Chapter 7.

2 Amendments 13, 14, and 15, "Constitution of the United States" at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/GPO-CONAN-1992/pdf/GPO-CONAN-1992-7.pdf. or https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/constitution-transcript. Last accessed October 01, 2017. The Russian Emancipation of the Serfs can provide a quick compare and contrast exercise. For primary source documents on this topic, see Alexander II, "Emancipation Manifesto," 1861, http://academic.shu.edu/russianhistory/index.php/Alexander_II,_Emancipation_Manifesto,_1861;" Alexander Nikitenko, "Alexander Nikitenko Responds to the Emancipation Manifesto," Documents in Russian History, http://academic.shu.edu/russianhistory/index.php/Alexander_Nikitenko_Responds_to_the_Emancipation_Manifesto. Last accessed September 14, 2018.

3 "Constitution of the Federal Republic of Argentina, September 25th, 1860," World Constitutions Illustrated HeinOnline, https://home.heinonline.org/content/world-constitutions-illustrated-contemporary-historical-documents-and-resources/, 3, 5–6. Last accessed September 11, 2018; Maria del Carmen Gress, trans., Organic Law or Political and Administrative Code of the Tunisian Kingdom (Apr. 26, 1861) (HeinOnline World Constitutions Illustrated Library 2014), 16–18; "Constitution of the Republic of Paraguay, November 24, 1870," 2, 7, World Constitutions Illustrated, HeinOnline. Last accessed September 11, 2018; "Constitution of the Republic of Nicaragua, March 30th, 1905," 2–3, World Constitutions Illustrated, HeinOnline. Last accessed September 11, 2018.

4 "Constitution of the French Republic, Adopted November, 1848," in Francis Lieber, On Civil Liberty and Self Government, ed by Theodore D. Woolsey, 3rd ed revised (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1883). Online Library of Liberty, last accessed 01 October 2017, http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/lieber-on-civil-liberty-and-self-government; "Constitution of the Republic of Uruguay, June 28, 1830." World Constitutions Illustrated. HeinOnline. Last accessed September 11, 2018, 2–3; "Constitution of the Republic of Nicaragua, March 30th, 1905," World Constitutions Illustrated, HeinOnline. Last accessed September 11, 2018.

5 "The Constitution of the Empire of Japan," from Hirobumi Ito, Commentaries on the Constitution of the Empire of Japan, translated by Miyoji Ito (Tokyo: Igirisu-horitsu gaako, 1889); Hanover Historical Text Project, at http://history.hanover.edu/texts/1889con.html. Last accessed January 5, 2019; "The Fundamental Laws of Persia," Human Rights and Democracy for Iran at http://www.iranrights.org/english/document-204.php. Last accessed September 03, 2018.

6 Instructors interested in a systematic analysis of what groups drove the constitutions and benefitted from their protections in nineteenth-century Central and South American constitutions should see Roberto Gargarella's work. Roberto Gargarella, "Towards a Typology of Latin American Constitutionalism, 1810–1860," Latin American Research Review 39.2 (2004), 141–453; Gargarella, Latin American Constitutionalism, 1810–2010: The Engine Room of the Constitution (Oxford University Press, 2013).

7 Luigi Lacchè, History & Constitution: Developments in European Constitutionalism: The Comparative Experience of Italy, France, Switzerland and Belgium (Frankfurt am Main: Vittorio Klostermann, 2016), 227–257;

Jörg Gerkrath, "Are Octroyed Constitutions of the 19th Century to Be Considered as 'Imposed Constitutions'?" in Xenophon Contiades, Richard Albert, and Alkmene Fotiadou, eds., The Law and Legitimacy of Imposed Constitutions (Rutledge ORBi at http://orbilu.uni.lu/handle/10993/31754). Last accessed 09/05/17. Papers from the conference "Imposed Constitutions: Aspects of Imposed Constitutionalism," May and June 2017 at http://www.iconnectblog.com/2017/04/conference-on-imposed-constitutions-aspects-of-imposed-constitutionalism/. See also https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228161592_Imposed_Constitutions_Imposed_Constitutionalism_and_Ownership. For further discussion, see Kelly L. Grotke and Markus J. Prutsch, eds., Constitutionalism, Legitimacy, and Power: Nineteenth-Century Experiences (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

8 Constitute: The World's Constitutions to Read, Search, and Compare, at https://www.constituteproject.org/. Last accessed January 5, 2019.

9 George Athan Billias, American Constitutionalism Heard Round the World, 1776–1989: A Global Perspective (New York: NYU Press, 2009).

10 "Constitution of the New Fante Confederacy," Modern Ghana News, at http://www.modernghana.com/news/123177/1/constitution-of-the-new-fante-confederacy.html. Last accessed September 03, 2018.

11 "The Ottoman Constitution;" 376–377; "The Constitution of the Empire of Japan," 4; "Constitution of the Federal Republic of Argentina," 9; Elizabeth Wallace, ed., The Constitution of the Argentine Republic, The Constitution of the United States of Brazil (Chicago: University Press of Chicago, 1894), 66. Google Ebook.

12 "Constitution of the Spanish Monarchy, June 18, 1837," World Constitutions Illustrated, HeinOnline. Last accessed September 11, 2018.