FORUM:

Art and World History

A Holistic Approach to Using Art to Understand a Historical Human Experience: Uncovering Meaning in Teotihuacan Murals

Kathryn Florence

Introduction

There is no more valuable material record of history than art. Events and dynasties are decorated with beautiful works of stone and gold, oil and precious pigments. One can utilize such inventories to quite literally illustrate the glory of empires and to calculate the wealth of nations. However, disciplines outside of art history have rarely approached art as anything more than a line of portraits, trinkets, preventing scholars outside of that discipline from fully exploiting art as an active agent in creating/reflecting belief systems and social structures, and the ensuing effects that art has had on world history. What is needed is for non-specialists in art history to adopt a holistic approach founded upon the disciplines of art history, anthropology, and archaeology.

The word holistic is itself an anthropological term referring to the comprehension of a part as intimately interconnected within a larger inexorable whole. The production of art is therefore foregrounded within the networks of religion, politics, identity, and several other facets of culture. This approach not only grants a more rounded understanding of the work of art, but also of the society behind it because it is treated as the medium of society. Holistic analysis is not alien to historians of world history, which is interdisciplinary in its approach to both research and teaching. This essay is designed to enable those less knowledgeable, less prepared, or for any reason reluctant to engage in holistic analysis to gain or improve their ability to 'read' art to access deeper insights into the culture and ideologies of past peoples. That effort is worthwhile, as there is so much more we can uncover about humanity and make world history much more sensible for students of the human experience, by looking a little closer at art.

Foundations of a Holistic Approach

The methodology for implementing this holistic approach is rooted in the recognition that a work of art is the result of implicit choices made by its creator to carry a culturally relevant message to a specific audience. It is the historian's task to unravel the artist's choices that led to its creation, the choices observers made in interpreting it, and the framework of socio-cultural cues that supply both,1 so that we can reach a greater understanding of the moment in time in which it was produced. Fortunately, that unraveling is less about how data is gathered, as it is about how we interpret the meaning of that data. This is because most basic information about artworks (i.e. date, location, patrimony) has already been gathered and is available through museum or web site catalogues, or printed books and journals.

What follows is a case study intended to illuminate the methodology of interpreting that data through the art objects we study as well as by gathering data that is only available through looking at the artwork. It also illustrates the next step, which is to move from what is clear to the senses (the last leaves falling off a tree in a Chinese painting) and raise the issue of what lies unseen in the art work (the artist expressing his sense of loss at the passing of a once great dynasty), all while keeping in mind the artist's point of view or that of his contemporaries (did it connect?).

The case study offered is an example drawn from my geographical area of expertise, Classic period (250 – 700 c.e) Teotihuacan, Mexico. It may seem to some that the material is too demanding of a reader's attention, but a close reading is rewarded by the many occasions in which the object in view demonstrates how much a single fragment of a fading fresco, like this one (fig. 1) from the Tepantitla Compound, can tell us about the daily life, politics and belief systems of an empire that was radically different from its neighbors and in its concerns both alien and familiar to ours today.

|

|||

| Figure 1: Mural 2 Room 2, Tepantitla Compound, Teotihuacan. Photo by Daniel Lobo, reproduced from Flicker under Public Domain. | |||

Historical Context

Establishing the time of a work provides an essential point of perspective. After all, the study of history is concerned with the timing of events. A scholar has to know what was going on at the time a work of art was painted.

Occupation of the famous archeological site of Teotihuacan, easily visited from modern Mexico City, began in the first century b.c.e. through a series of hamlets and villages. In the following century of the new millennium, the massive platforms of the Pyramid of the Moon and the Pyramid of the Sun were built at the culmination of the Avenue of the Dead, followed swiftly by the Feathered Serpent Pyramid.2 A secondary phase of construction occurred directly after, wherein the Pyramids take their current megalithic proportions.3 Then something catalyzed in the Tlamimilolpa phase (200-350 c.e.). The residential structures that originally housed the vast majority of the population were demolished and an urban revival was initiated.4

The Tepantitla Compound under study dates to the Xolapan (350-550 c.e.) or Metepec (600-750 c.e.) phase as indicated by the pottery included in inhumations at the site, which followed the city's renovation.5 Its presence is located squarely at the height of the city's rise to power within the Mesoamerican world. Therefore, all of the information being derived from the following analysis would be indicative about the flourishing of a Classic Period center. Because of this we can account for interregional contact and exchange.

Geographical Context

Location is a key factor in historical analysis. We must account for the location of the site and of the particular work of art as a part of the site.

|

|||

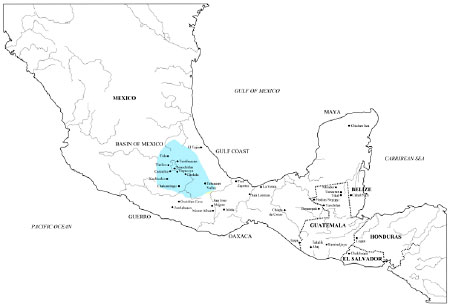

| Figure 2: Map of Mesoamerica highlighting the Central Basin. Reproduced courtesy of author. | |||

Teotihuacan was located at the crossroads of the western Guerro region and the Gulf Lowlands, in the Basin of Mexico (fig. 2). It was therefore an unavoidable middleman in trade.6 Teotihuacan was also a center of production as well as mediating between other centers. Teotihuacan sustained an industry of obsidian, lime, cotton, and distinctive thin orange pottery.7 There is evidence of several scales of production operating at once during the height of occupation.8 This indicates that there probably were a variety of interregional influences flowing into the city along with goods. Unfortunately, spectrometry tests have not been carried out on the priestly mural. Subsequently, we cannot say where the pigments were sourced from or what this might say about trade. Nonetheless, we can be safe in assuming that the paints contained materials sourced through trade.

The city itself covered 20 sq. kilometers organized around two perpendicular avenues. The massive pyramids that we are used to seeing constituted the 8 sq. kilometer ceremonial heart of the state. Along this promenade are the most important buildings previously alluded to, the Pyramid of the Moon, the Pyramid of the Sun, the Feathered Serpent Pyramid, and also the Ciudadela, and the Avenue of the Dead complex. The sweeping avenue integrated the city on both a symbolic and instrumental level.9

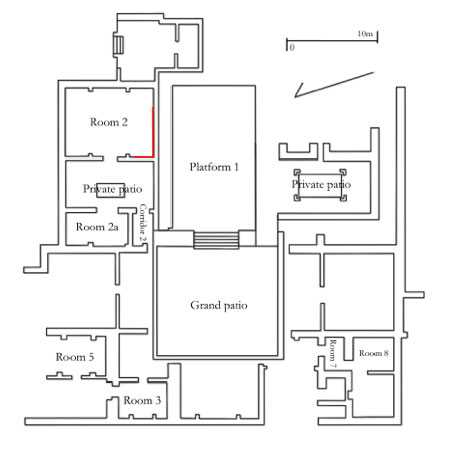

Encapsulating the remaining 12 sq. kilometers were apartment compounds. The Teotihuacan Mapping Project estimates that there were approximately 2200 compounds within the center limits now covered by neighboring farm fields, of which only twenty or so have been excavated.10 Along one of the walls of room 2 in the Tepantitla Compound is where we find the priestly procession mural, also known as mural 2 and 3 in archaeological notes (fig. 3). It would have been part of a larger mural, like that from the Atetelco Palace, also from Teotihuacan (fig. 4)

|

|||

| Figure 3: Plan of Tepantitla Compound with highlight of Murals 2 and 3, after Fuente 1995:183. Reproduced courtesy of author. | |||

|

|||

| Figure 4: Detail of the murals in the Atetelco Palace in Teotihuacan. Photo by Jortegacillero. Used under Wikicommons Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. | |||

The apartment compound housing unit held multiple consanguineal [related by blood] lineages that could consist of families of thirty to over a hundred persons. The insides were a jumbled mess of rooms that were connected like a maze while the outside facade presented unified austerity. The patios could be used for the worship of family gods or ancestors. This was a place for ritual, for belief to be expressed in more intimate terms. The art that was painted here was not to make a grand statement to an anonymous public. It was the background to daily life.

Subject Matter and Symbolism

Mural 2 depicts three figures in priestly attire in a ceremonial procession around the lower portion of the patio wall, though we will be focusing on only one of them, as they are nearly identical.

The background is awash in ferrous red, like the color of blood. Three human figures march across a barely visible ground line. In one hand is a copal (a sweet incense) bag, the other is tossing seeds and offerings. Spiraling upwards are two speech scrolls, indicating recitations and praises. They are draped in layer upon layer of elaborate paraphernalia. The most striking part of the costume is the massive feathered serpent headdress.11 The painted face of the priest appears to emerge from the snarling maw of the great beast.

What is being depicted is important, and so is what is not being depicted. From the first indications of collective identity, the jaguar was the iconographic 'king' of the Mesoamerican world. Its pelts were the symbol of rulership, draped over the shoulders and hips of the urban center lords. The Olmec claimed descendance from supernatural jaguars and based their claim to rulership on these lineages. To them, there was nothing more noble, fierce, or powerful than the feline predator. Therefore, the deliberate substitution of the Feathered Serpent for the Jaguar is an ideological rejection of what the feline represents. In essence, Teotihuacan was visually saying that they were not concerned with a lord.

The archaeological record of Teotihuacan enforces this notion. The site offers no stelae graced with the stone faces of grandiose rulers. There are no texts proclaiming the great deeds of so-and-so or the venerable heritage of such-and-such. There is a distinct lack of ruler imagery or evidence of the governing structure, especially in the art. None of this is to say that Teotihuacan was a fully egalitarian society. Far from it. Teotihuacan expressed a hierarchy symbolized by the costumes worn by persons.12 Yet, while they emphasized these different ranks, the individual was kept out of the spotlight as will be discussed in the next section.

At a glance, this fresco tells us that the city had a priestly caste and rituals involving the offering of copal. However, when we look closer we uncover the extraordinary religio-political system that distinguishes Teotihuacan from the rest of Mesoamerica. Painting the walls of the patio with a priest dressed in the headdress of the primary god indicates the prevalence of state religion even within the practice of personal rituals. But the government is impersonal, uninterested in glorifying a lord-based system. No other site has indications of such a political system.

Patronage/Audience

There are two key players in this question. Who is the patron and who is the audience? (I do not intend to attempt to identify the priest depicted in the mural. As already pointed out in the previous paragraph and will be discussed in the following section that was deliberately made to be impossible.) From its location we can discover for whom it was intended and how that relates to other social practices carried out within the residential area of the city.

Several family groups inhabited the apartment compounds at a time. Each family had their own ancestors to venerate and appease. Given the intimate setting and seclusion from the other room modules, we can point to the family of Room 2 as the patrons of the mural.

As stated earlier, the inner patios of the apartment compounds were for private use by the compound's inhabitants, and more so for the smaller private patios which were for use by specific families. Therefore, only the families that inhabited the compound would have access to the murals. The obvious answer is that the family members of Room 2 were also the intended audience. And this would be correct. However, we have to remember that more than just humans inhabited the Mesoamerican world. Family gods and ancestral spirits would also be considered as the audience to the painting even though it stands just outside of the patio.

The Mesoamerican world did not draw such bold lines between belief and witness. Mesoamerican religious beliefs shaped the very world around them and how they understood it, much like the Catholic Church shaped that of the Medieval period in Europe. These worlds were inhabited by a host of creatures both biological and fantastical. These beings controlled every aspect of life from birth, to love, to death, to corn, to alcohol, etc. They were everywhere. And they were not to be trifled with. Why would a spirit care about a painting of a priest? Why would the head of a household have a priest painted for a spirit? The depictions of priests in perpetual piety might have been a tactic to assuage the inhabitants of the other worlds into looking kindly upon the members of the household, just as a wealthy lord might have his portrait placed in a church to illicit posthumous prayers for his immortal soul.

We can gather from this line of inquiry that ritual formed a cornerstone of daily activities in Teotihuacan. Culturally, religion served as an ever-present reminder of the duties of humans to the gods. Mesoamerican belief placed the burden of sustaining existence on humanity. Through their blood was the sun and earth fed, and the gods satiated. Even the average commoner had a debt to be paid in rites. The presence of a priestly procession within a private ritual patio indicates the importance of religion and the presence of mythic forces throughout daily life.

Style

Style is a characteristic feature of art historical analysis. Here it will be used to expand upon the creation of social relations and ethnic identity. Teotihuacan art is abstract. As seen in this fresco, human figures are stiff and blocky. They seem more like schematics of a person than actual portraits. There is no ground line, no perceptual depth. Figures dance through voids of flat color. In essence, the art was not trying to create a representation of a real event or place. It is about emphasizing the message beneath the pigment. Symbolically, abstract art is about dissociating. It strips back anything that is not essential to the vision. Given the contemporaneous network of polities whose canons overflow with complex images, this is another drastic omission on the part of Teotihuacan.

From this we are presented with a program of art that is intentionally avoiding the stylistic influences of its neighbors. In a city such as Teotihuacan, which was made up of immigrants, refugees, and locals, it makes sense. Associating the site with an outsider style might incidentally alienate some of the groups who lived within its borders. This would cause unrest in such a claustrophobic setting. Therefore, they wiped away all traces of affiliation to avoid implied preferential associations. The abstraction of forms erases regional cues that migrants to the city would have brought with them. In this way Teotihuacan stressed their collective identity as a polity in order to forge cohesion amid groups living within its limits.

Purpose

This is perhaps the most important question of the six because nothing is made without reason. The notion that art is to be made for art's sake is a modern one, having been founded only within the past century and a half, and it rarely holds true today. Even vigilante graffiti artists have a reason for spray-painting their tags across back alleys (and it is not just for the kicks). Art is made through several intentional choices on the behalf of the artist and the patron, which are themselves dependent on being culturally readable in order to be effective. It is a deliberate, active agent in contesting, creating, catalyzing the very culture that produced it. While our perceptions of the function of art have changed over the centuries that does not necessarily exclude us from attempting to experience it as it was intended to originally. But to do so, we first need to take the stance that art is more than aesthetics.

This work of art was made because it was a declaration of belonging. It says 'I am a Teotihuacano' at the same time it instructs them in what it means to be Teotihuacano. The mural was painted as an extension of the ideology that founded the city itself. It was a means to honor the familial dead remembered in that patio. It is a dedication to the god that ensures the continuation of time itself. It is a rejection of a feudal social system. The inhabitants of Teotihuacan developed a distinct identity despite the multiethnic composition of the population. Debra Nagao, Claudia Garcia-Des Lauriers, Kiri Louise Haggerman, and Jennifer M. Foley are just a few notable scholars who have also explored the expression of Teotihuacan identity in the archaeological record.11 And as shown here, it tells us about a cult, a city, and a citizenship at the height of an empire.

Applying Art to Understand and Teach World History

We have been looking at art instead of looking through it. It is my hope that this brief article has expanded the avenues through which the study and teaching of world history may be carried out. Just like art, culture, history, and society are created by the minds of humans. Thus, to ignore the most human product from investigation is to brush aside an invaluable source of first-hand information. I will cede art is not without its faults to misinterpretation. However, it is no more subject to such failings as the textual record. History is written by the victors. At least art lets us see what they intended to be seen. Therefore, we can use art to teach the multiple narratives of history and the implications of their construction. For example, comparing the Cortez map and Codex Xolotl can be used when used to discuss the clash between the Old World and the New, between European ontology and Indigenous reality during the sixteenth century, between the organizations of power within their society, between concepts of the land they were depicting.13 Or we can examine how Botticelli's famous Primavera reveals tensions between the Catholic Church and the Classical revival that typifies the Renaissance, the networks of trade that connected the states of Italy to the wider world, and even the performance of gender in a newly established merchant class.

Teotihuacan presents itself as an opportune example for teaching the development of civilization in the Americas. The site, as this article has shown illuminates how governmental organization can mold the physical layout of a city. As well, it illuminates how said system drew in and then managed a diverse population within its territory. From its walls we can see how ideas were traded among the goods passing through the market center.

Conclusion

This article has shown that a single piece of art can illustrate paradigms of belief, organization of government, and the ideology of statehood. This holistic approach, as secured through a contextualizing methodology, provides students with a visual means of relating major events in history to everyday institutions and norms. Art is an invaluable source of such information, especially when a society leaves no textual records. Students can access the intangible aspects of culture by analyzing art works through historical context, geographical context, subject matter, patronage, audience, style, and purpose. I hope that I have shown the opportunity that exists within the layers of paint and plaster.

Kathryn Florence received her undergraduate B.A. in Art History and Honors Anthropology from Purdue University, West Lafayette. She is currently pursuing a Masters of Arts in Art History at Concordia University, Montreal. Florence is the founder and Executive Director for the Canadian Latin American Archaeological Society (CLAAS), a non-for-profit organization dedicated to promoting new studies about ancient Latin American societies and providing a platform for the sharing of recent research. She is currently revising for publication, Fang & Feather, a manuscript of her research about the origin of the Plumed Serpent as a symbol of Teotihuacan common action government, in direct opposition to Maya lord-led polities symbolized by the jaguar. She can be reached by email at kathryn.m.florence@gmail.com.

1 Art is not—nor has it ever been—a mere reflection of the society that bore it. It is a medium of communication, a mode for us to convey emotions, ideas, events, etc, from the emic (the insider's) point of view to the etic (the non-insider) observer.

2 Doris Heyden, "An Interpretation of the Cave Underneath the Pyramid of the Sun in Teotihuacan, Mexico," American Antiquity 40, no. 2.1 (1975)139.

3 Gillian Elisabeth Newell, "A Total Site of Hegemony: Monumental Materiality at Teotihuacan, Mexico," (Ph.D. dissertation, The University of Arizona, 2009),102.

4 Laura E. Beramendi-Orosco, Galia Gonzalez-Hernandez, Jaime Urrutia-Fucugauchi, Linda R. Manzanilla, Ana M. Soler-Arechalde, Avto Goguitchaishvili, and Nick Jarboe, "High-Resolution Chronology for the Mesoamerican Urban Center of Teotihuacan Derived from Bayesian Statistics of Radiocarbon and Archaeological Data," Quaternary Research 71, no. 2 (2009),106,

5 Jennifer Kathleen Browder, "Place of the High Painted Walls: The Tepantitla Murals and the Teotihuacan Writing System" (Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, 2005).

6 George L. Cowgill, Ancient Teotihuacan: Early Urbanism In Central Mexico (London: Cambridge University Press, 2015),78; Linda R. Manzanilla, "The emergence of complex urban societies in Central Mexico: The case of Teotihuacan," in Archeology in Latin America, edited by Gustavo G. Politis and Benjamin Alberti (London: Routledge, 1999),93-129.

7 David M. Carballo, "The Social Organization of Craft Production and Interregional Exchange at Teotihuacan" in Merchants, Markets, and Exchange in the Pre-Columbian World, eds. Kenneth G. Hirth and Joanne Pillsbury (Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2013),121.

8 Linda R. Manzanilla, "Corporate Life in Apartment and Barrio Compounds at Teotihuacan, Central Mexico," in Domestic Life in Prehispanic Capitals: A Study of Specialization, Hierarchy, and Ethnicity, eds. Linda R. Manzanilla and Claude Chapdelaine (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan The Museum of Anthropology, 2009), 46:31.

9 Shawn G. Morton, Meaghan M. Peuramaki-Brown, Peter C. Dawson, and Jeffrey D. Seibert. "Civic and Household Community Relationships at Teotihuacan, Mexico: A Space Syntax Approach," Cambridge Archaeological Journal 22, no. 3 (2012)395.

10 Ian G. Robertson, "'Insubstantial' residential Structures at Teotihuacán, Mexico," online report (San Francisco: FAMSI, 2008), 3.

11 Scholars have previously identified this as a crocodilian headdress. While this would be logical and plausible, given the place of the Plumed Serpent in the ceremonial complex of the site, it is far more likely that this is actually a Feathered Serpent.

12 George L. Cowgill, "Social Differentiation at Teotihuacan," in Mesoamerican Elites: An Archeological Assessment, eds. Diane Z. Chase and Arlen F. Chase (University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 1992), 206-220; George L. Cowgill, Ancient Teotihuacan: Early Urbanism In Central Mexico (London: Cambridge University Press, 2015),208.

13 Debra Nagao, "An Interconnected World? Evidence of Interaction in the Arts of Epiclassic Cacaxtla and Xochicalco, Mexico," (Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University, 2014); Claudia Garcia-Des Lauriers, "Public Performance and Teotihuacan Identity at Los Horcones, Chiapas, Mexico," in Power and Identity in Archaeological Theory and Practice: Case Studies from Ancient Mesoamerica, ed. Eleanor Harrison-Buck, Foundations of Archaeological Inquiry (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2012); Kiri Louise Hagerman, "Domestic Ritual and Identity in the Teotihuacan State: Exploring Regional Processes of Social Integration Through Ceramic Figurines," (Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, 2018); Jennifer M. Foley, "When Worlds Collide: Understanding the Effects of Maya-Teotihuacán Interaction on Ancient Maya Identity and Community," (Ph.D. dissertation, Vanderbilt University, 2017).

14 Kathryn Florence, "Making Monsters, Maps and Empires: How Conquest Period Spanish and Aztecs Encoded Myth in the Cartography of the Basin of Mexico." Presented at Making the Map: Cross-border and Intercultural Representations from Ancient History to Today. Université de Haute-Alsace, Mulhouse, France.