Jesuit Education in Contemporary Urban India: A Study in Global Institutional Change

Luke Sullivan and Howard Spodek

|

|||

| Figure 1: The Portuguese arrive in Goa, 1510. Modern commercial ceramic tile mural, c. 2000, Panjam, Goa. Photograph courtesy of Marc Jason Gilbert. | |||

From its inception, the Jesuit order established an international presence, reaching India as early as 1542 when St. Francis Xavier arrived in Goa, the capital of Portuguese India. Their mission was two-fold, spreading education and winning converts. Much has been written about the Jesuit mission in its early years, but very little about the transformative changes that have taken place within the past half century.

One study that does address changes within the order, focusses on Fr. Ramiro Erviti, a Spanish Basque priest who taught at St. Xavier's High School in Ahmedabad, western India, 1956–86. A number of Ahmedabad's most distinguished civic leaders studied under Erviti. Many had their first experiences working with slum dwellers and urban poverty through their engagement with him.1 The priest's concentration on alleviating poverty and deprivation was a local example of a new initiative for the Jesuits, who had previously focused on the classical education of elites and, sometimes, the conversion of non-Catholics.

In 1991, five years after Erviti's death, a new challenge to Jesuit education arose, this time originating outside the Church. India liberalized its economy and new private schools and colleges sprang up competing for elite students, capable of paying high tuition fees, and forcing the Jesuits once again to re-evaluate their mission and resources.

Few scholarly studies have attempted to situate these two profound transformations—the increased concern with the poor and the necessity to compete in a new educational marketplace—within the context of rapid change in the Church, the nation, and the school system. The present essay, which begins locally, with one priest in one school in one city in one country, is intended to help pave the way to more global studies of the Church, the Jesuits, the nation, and educational innovation more generally.

To understand and fully appreciate such institutional restructuring requires a brief review of historical events spread across the globe over five centuries, including: Jesuit missionary activity in the Portuguese empire, especially in Goa; British colonial policies in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; policies of the new, independent government of the India after 1947, as well as the individual state governments; priorities of the Indian economy after liberalization in 1991; the rise of a militant Hinduism—Hindutva—in the 1980s; the re-orientation of the Catholic Church, especially following the resolutions of Vatican II in the mid-1960s; and the decline by half in the numbers of Jesuit priests globally.2

History

St. Francis Xavier, one of the founders of the Jesuit order, reached Goa, the capital of Portuguese India, in 1542 as Pope Paul III's apostolic nuncio in the east, and in response to the urging of King John III of Portugal seeking Jesuit missionaries who could restore discipline among the Portuguese settlers who were not properly following Catholic teachings.

|

|||

| Figure 2: A Japanese artist's depiction of St. Francis Xavier dated to the 17th century. Detail. Artist unknown. Public domain. Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/db/Franciscus_de_Xabier.jpg. Xavier's mission took him to India, Southeast Asia, China and Japan. | |||

In addition to acting as a missionary to lapsing Catholics, Xavier also set out to convert Hindus and others to the Faith.3 He saw education as a means of outreach to Catholics and evangelization of non-Catholics. In the year of his arrival he established the first Jesuit school in India to serve both Indian and Portuguese boys. In the early days, the schools established at Xavier's mandate were entirely free and were designed to attract the children of the poor and lower castes, to restore the Portuguese to Christian practices, and to extend missionary work to Hindus and others.4 To augment the work, "the first printing press in India was set up by Jesuit priests in Goa."5 To help fulfill his tasks, Xavier called for the Portuguese Inquisition to set up also in Goa, although he died before it began in 1561. The Inquisition had unintended consequences. Its cruelty and intolerance were "disastrous for missionary activities in India generally."6

The Jesuit numbers were always few. In 1773, when Pope Clement XIV suppressed the Jesuit order, there were only two Jesuit provinces in India, Goa and Malabar; 228 Jesuits were working there, serving existing Catholics and attempting to convert more.7

By the time the Jesuit order was reinstated by Pope Pius VII in 1814, the British had conquered, or were in the process of conquering, most of India. As the Jesuits returned to India, they founded missions in Madurai (1838), Bombay (1858), Bengal (1859),8 Calicut-Mangalore (1878), Goa (1890), and Patna (1919). The priests were dispatched from different areas of Europe. The Jesuits of the Bombay Presidency – which included present day Ahmedabad—came from the Upper German Provinces.9

Apprehensive lest missionary activity disturb Indian religious sensibilities and evoke revolt, the British East India Company, and later the British Crown, limited missionary activity. Jesuits nevertheless continued their missionary activities in rural areas. In cities they concentrated on educational institutions, especially colleges that might make Christian principles and lifestyles clear without attempting directly to win converts. A remarkable article in The Catholic World, of June 1897, explained the Jesuit approach at the time.10 In five large colleges spread across India they served Indian Catholics as well as others who might want to attend. The largest college at the time was St. Xavier's, Bombay, with 1400 students. The most diverse was St. Xavier's, Calcutta, with 800.

St. Xavier's College, in Calcutta, is a striking proof of the hold that the [Jesuit] fathers have on the mixed population of the empire. The sight presented to a visitor during one of the recreation hours is as varied as any sight could be and would delight the heart of the most intense yearner after the universal brotherhood of mankind. Europeans, Catholics, and Protestants of every shade of difference, Eurasians of every color, Hindus, Mohammedans, Persians, Burmese, Assamese, Jews from many countries, Armenians, Japanese, Greeks, and Chinese-all these, different in character, manners, and dress, and in many cases naturally hostile to one another, mix amicably together, bound by a common language and by the kindly spirit of their Alma Mater.11

Figure 3: A view of St. Xavier's College, Kolkata, largely unchanged since 1900. Photograph made in 2012 by Snehal Kanodia, Under the professional name Snehalkanodia, Ms. Kanodia has created many beautiful images of the College and other locales. Her portfolio can be accessed at http://www.snehalkanodia.com. Used with her permission.

The Jesuit fathers were winning over the hearts, if not the souls, of their students:

They quickly perceived that the only way to make an impression on the educated classes was to raise the Church in their eyes by making her the channel of an education at least equal to any that could be procured outside her. … the suggestions of a religious character conveyed by the Jesuits with their secular teaching, together with the example of their humble and devout lives . . . [may evoke conversions] and our holy religion [will] be enriched by the adherence of a vast multitude of intelligent and clever followers.12

Later in life, these students, though not converted, "are proud to own St. Xavier's as their Alma Mater and are generous in offering medals for deserving students and founding scholarships in the college." (300).

Many of the faculty and the administrators were foreign-born Jesuits. During World War I, the British expelled the German-born; Jesuits from elsewhere in Europe replaced them. In Ahmedabad, the newly arriving Jesuits came mostly from Spain, some transferring from postings in the Philippines. The Government of India expressed surprise that, even after so many centuries, the Church had not succeeded in training Indian priests and professors for their seminaries.13 Indian Catholic bishops raised similar concerns and determined that they must begin to recruit and train their clergy and administrators locally.14

In the late twentieth century the changing demographics of the world-wide Jesuit order made local recruitment imperative. The number of European-born Jesuits sharply reduced while the Indian-born increased. Internationally, the population of Jesuits was shrinking dramatically, from 36,038 in 1966 to 15,842 in 2018.15 Almost a fourth of the entire Jesuit order—23%; 4016—now live in South Asia.16 The region "is home to the majority of Jesuit schools in the world."17 As of 2017, there were 391 Jesuit schools in India with approximately 12,000 teachers serving approximately 400,000 students.18

|

|||

| Figure 4: St. Xavier's High School, Ahmedabad, 2019. Photograph courtesy of Howard Spodek. Statue is of its namesake. | |||

In India, a country of 1.3 billion people, these number are comparatively small, but the influence has been great. Many of the products of the Jesuit schooling system came from elite backgrounds and rose to hold elite positions. India is only 2% Christian, so although a proportion of places is reserved for Catholics, most of the students within the Jesuit educational system are Hindus and Muslims.

The efforts of the Jesuits were mostly appreciated for the new perspectives and skills they taught, but they were also criticized as handmaidens of the imperial mission. As K. M. Panikkar wrote in 1953: "It may indeed be said that the most serious, persistent and planned effort of European nations in the nineteenth century was their missionary activities in India and China where a large-scale attempt was made to effect a mental and spiritual conquest."19 That conquest through education was targeted at the elites. For the most part, only the elites could afford the fees.20

In recent years, however, because of changed admission policies within the Jesuit order, the students are increasingly drawn from tribal communities and members of low castes. The move to focus attention on the poor began from Rome in 1962, when Pope John XXIII convened the Second Vatican (Ecumenical) Council to more clearly define and establish Church doctrine in light of the changing values of the modern world. Vatican II especially emphasized the importance of the Church's service to the poor and the general human community. The liberal rhetoric of Vatican II manifested itself at the next meetings of the General Congregations of the Society of Jesus.

The General Congregations and the Jesuit Educational Association Reaffirm the Mandate for the Poor

General Congregations are convened about every ten years, when leadership passes from one Superior General to the next. Provincial Superiors and other representatives meet in Rome and formulate decrees to be followed by the Jesuits worldwide. The Thirty-First General Congregation held its opening meeting in May 1965, several months before Vatican II completed its deliberations. It emphasized the importance of selecting students "as far as possible, of whom we can expect a greater progress and a greater influence on society, no matter to what social class they belong."21 It called on teachers in Jesuit schools to make their students more aware of social injustices and instill a desire to correct them. With its famous Decree 4, the Thirty-Second General Congregation, 1974–75, committed the Society to "the service of faith, of which the promotion of justice is an absolute requirement."22

The Jesuit Educational Association of India (JEA), comprised of all the Jesuit educational institutions in South Asia, was constituted in 1961. Their first seminar, titled The Social Mission of the Jesuit School and College, took place in Mumbai, in 1968, and concluded: "In all activities of the institution, and in particular in the admission policies, we must publicly demonstrate our commitment to the need for equalization of opportunities between the various classes of the population."23 The next National Seminar, in 1973, recommended that "Students should be trained to combat social injustice through indirect peaceful action."24 Another national seminar, held in Pune in 1986, stated that "The poor must be our primary concern; every aspect of our educational endeavour must be seen from their point of view."25

A JEA evaluation report from 1994 reported some success. Many disadvantaged students were attending Indian Jesuit schools.26 The Superior General of the Society of Jesus, Peter Hans Kolvenbach, addressed a letter to the National Seminar in 2003 urging the Jesuits to "favour dalits [formerly untouchables], tribals and other marginalized groups" in their admission policies. 27 Fr. Xavier Alphonse, former principal of Loyola College, Chennai, and two-time member of the Central Government's University Grants Commission, clearly linked the problem of poverty with the problem of caste and tribal discrimination. He recommended alternative non-formal vocational programs to further support these disadvantaged populations. In 1996 he promoted the creation of the Madras Community College, the first Jesuit community college in India.28

Informal and Non-Formal Education

We have focused thus far only on formal education. But many Jesuits – including Fr. Erviti—began to turn to non-formal vocational programs and programs of direct service to the poor and those of low caste and tribal status. The organization "Jesuits in Social Action" was formed in 1973 to help implement these policies:

Jesuits in Social Action (JESA) South Asia Secretariat was formally initiated in 1973 to assist the Major Superiors to translate the faith – justice mandate of GC 32 into action in all the ministries and in particular in social action ministry of the Society of Jesus. The primary function of JESA is to encourage and elicit well-studied and analyzed responses and interventions from Jesuits and collaborates in favor of and with the marginalized groups and communities. It would further promote and coordinate ongoing action-reflections, interactions, research/study and actions leading to greater development and empowerment of the priority communities. It would also gather and disseminate information and knowledge through bulletins, workshops, seminars, training, and visits.29

In Ahmedabad formal and informal education initiatives overlapped. Jesuits teaching in formal schools and colleges also initiated informal education institutions. Fr. Erviti and his friend and colleague, Fr. J.M. Heredero, were leaders in this movement. Each established a new, separate institution for his work; each of these institutions was situated adjacent to the formal institutions where they continued to teach.

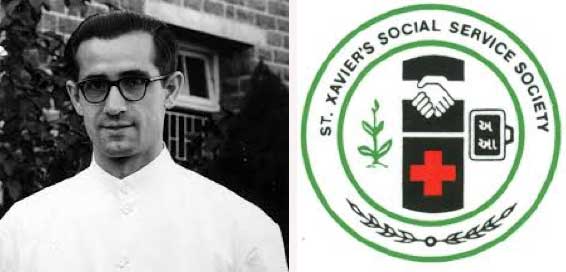

Fr. Erviti and the St. Xavier's Social Service Society to Serve the Poor

|

|||

| Figure 5: Fr. Erviti photograph from article in Jesuit Education, used with permission of the editor. Also, the emblem of the St. Xavier's Social Service Society Fr. Erviti created. | |||

Fr. Erviti created the St. Xavier's Social Service Society, directly across the street from Loyola Hall, to bring his relatively privileged students to work with Ahmedabad's slum dwellers and immigrants from tribal areas. Many of the leaders of Ahmedabad's most prominent NGOs credit Erviti with their first experiences in the slums and the resulting inspiration to serve the poor. Their essays and interviews collected in Creating Citizens: Fr. Ramiro Erviti in Ahmedabad, 1956–86 tell the story.30 Many of the book's contributors, from both sides of the social and economic divide, also reflect on the importance of the character building that came from their participation in Erviti's camping and mountaineering expeditions.

In 1977, Fr. J.M. Heredero founded the Behavioural Science Centre on the grounds of St. Xavier's College where he taught political science and served as rector in the student hostels. Working closely with Pheroz Contractor, a Parsi, and Burhan Siddiqui, a Muslim, he carried out research in the problems of poverty and discrimination, especially among dalits. They found that the varna system—the value system underlying the caste system—affected the psyche of dalits leading to a very low self-image, psychological exploitation of the most damaging form. With the help of Paolo Freire's pedagogy,31 the BSC developed an effective educational method to counteract the varna ideology and prepare people at the grassroots to undertake developmental programs.32 Cooperatives promoted by the BSC were awarded the Indira Vrikshamitra award for developing social forestry in 1988. More famously,

the BSC began conscientization work among the Vankars [one group of dalits] of the Khambat area [specifically, Golana Village, about fifty miles from Ahmedabad]. When the Dalits took up the fight to [take control of] the land which was allotted to them by the Government, the upper castes intimidated them and murdered some [four] of the leaders of the Dalits in 1986. The Centre took up their case in the Supreme Court on behalf of the oppressed Dalits and Vankars and succeeded in getting [many of] the upper caste perpetrators convicted.33

The Behavioural Science Centre provided the seed out which has grown today's Human Development and Research Centre of St. Xavier's Non-Formal Education Society.34 It supports research on programs for the poor and monitors the degree to which government implements the social welfare activities that it mandates.35

As the total number of Jesuits declined and as the informal programs proved their efficacy, several of the younger Jesuits, whom we interviewed at their Premal Jyoti training Center in Ahmedabad, expressed a greater interest in informal projects of social and economic development. They believed these projects to be more effective than formal education in serving and empowering the poor and in lowering costs.

Financial and Structural Problems in Formal Education

The principal activity of the Jesuits, however, remains formal education. In 2013 there were 189 Jesuit universities or other postsecondary institutions around the world. 54 of them in India. "… In South Asia alone (primarily India), the Jesuits are responsible for 229 secondary schools plus another 164 primary and middle schools."36

The changes in admission policies confronted Jesuit schools and colleges with financial constraints. Already in 1987, the leader of the JEA, Gregory Naik "realized that the financial implications of the option for the poor will mean that we [must] seek grant-in aid."37 Government grants, however, brought government regulations.

Fr. Sunny Jacob, currently the head of the Jesuit Educational Association of South Asia (formerly the Jesuit Educational Association of India),38 stated that currently in Indian Jesuit schools "the Boards [curricula] have been set by the government, exams for the students have been prepared by the government, we have no freedom to make our own curricula. We used to make our own textbooks—now no more." In India, schools utilize different Board curricula, such as the CBSE [Central Board of Secondary Education], the ICSE/ISE [Indian Certificate of Secondary Education] and an array of different State Boards. These Boards dictate which textbooks the students use and which exams they take from kindergarten to the twelfth standard (grade). State Boards vary in quality. The National Boards are the usual choice of students (and their parents) wishing to stand for national level tests and entrance exams for more highly ranked colleges.

In a 2011 article, K.S. Chalam identified three types of schools in Indian society: "one, the ill-equipped municipal or panchayat school where children of the poor study; two, the grant- in-aid private school where a fee is collected and the middle classes send their children; and the so-called public school39 or convent where the children of the rich and elite get educated in high-tech air conditioned classrooms."40 Jesuit schools in India previously came under the third category but now, after shifting their admission policies in the late 1970s and the mid-1980s, they generally fall under the second. Most Jesuit schools now take funding from the government to supplement the reduced tuition fees from students.

Still they retain some level of freedom in the Moral Science and Catechism classes they teach. Because the Jesuit schools teach mostly Hindu and Muslim students, these non-Catholics attend Moral Science classes while Catholic students attend Catechism classes. The Moral Science classes emphasize general humanist values and focus on topics such as the morality underlying secular documents, especially the Indian Constitution, and those pertaining to global human rights issues. A recent study of global Catholicism notes that this emphasis on humanist values and global human rights now permeates Jesuit education everywhere:

In the wake of two world wars, decolonization, and the Second Vatican Council (1962–65), the Society of Jesus renewed its global commitment in a new idiom, emphasizing the promotion of justice and the universal common good as part of the service of faith.41

Accommodating Threats from Hindutva

The Jesuits in India today have extra reason for caution in their teaching of morals and values: the dangers inherent in being perceived as straying into attempts at conversion. Minority institutions in India today exist within the majoritarian culture of Hindutva that surrounds them, a culture that merges Hinduism with politics. The principal political vehicle for the rise of Hindutva has been the political party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).42 The destruction of the Babri Masjid in 1992, especially, marked this rise. Supporters of Hindutva, and the BJP, destroyed a mosque in the north Indian city of Ayodhya, claiming that it had been built on the site of an earlier Hindu temple dedicated to Lord Rama and situated on his exact birthplace. They claimed the temple had been destroyed by Muslim invaders five hundred years earlier and they vowed to rebuild it.43 Through popular, but provocative, militant actions like these, the BJP slowly consolidated its political power until it won a majority in a coalition government in the lower house of the Indian Parliament in 2014, and an absolute majority in 2019. With the rise of Hindutva, violence against minorities, especially Muslims, but also Christians, has increased.44 Although most of the instances of violence have taken place in rural areas45 they evoke apprehension also among urban Jesuits, and Christians generally. Gujarat State in particular, and Ahmedabad City even more particularly, are locations for caution for minorities, although more for Muslims than for Christians. In 2002, following an attack by Muslims on a train carrying Hindu pilgrims from Ayodhya that left 59 dead, Hindu mobs killed some 2000 Muslims across Gujarat State, about half of them in Ahmedabad. (Official government reports give totals about half of these numbers, but reliable outside observers give these figures. About a fifth of those killed in the violence were Hindus.) 46

Several interviews with Jesuit priests working in schools in Gujarat reflect their caution in teaching Christian values and Ignatian principles without being accused of insulting Hinduism or attempting conversions. Teachers at St. Xavier's Loyola Hall High School in Gandhinagar (capital of Gujarat State, about 20 miles from Ahmedabad), felt that Christian schools were under especially close scrutiny. For example, in 2018, a teacher in a Catholic school in Gandhinagar removed a rakhi, a wristband with Hindu religious significance, from a student's arm just after the Hindu festival of Rakshabandhan. The BJP led protests outside of the school and took the issue to the state board of education. Many Jesuits, especially those outside of urban centers, believe that they are falsely accused of attempting to convert their Hindu students. They also feel somewhat less protected than previously. Their earlier graduates were more elite, with more power to provide a buffer against false attacks; the newer generation are less powerful, less able to provide protection.47

From Global to Local

To understand how larger international and national policy changes in Jesuit education, have affected institutions at the local level, we turn now to our case studies of St. Xavier's College and St. Xavier's High School Loyola Hall in Ahmedabad. Printed materials are scarce, so we rely heavily on interviews. Although they are largely anecdotal, they remain consistent in representing the major changes in the Indian Jesuit educational system.

The Jesuit mission in the Gujarat region48 had only two educational institutions prior to Indian Independence. In the next sixteen years, however, 1947–63, ten high schools and St. Xavier's College were founded. In the 1980s, Jesuit schools continued to expand in Gujarat. In keeping with 'the option for the poor,' particular emphasis was placed on opening schools in poor rural areas.49

Meanwhile, from the 1990s to the present, general education in Gujarat has become increasingly commercialized and "so more challenging for Jesuit education," said one state level official in Gandhinagar. 50 As Suguna Ramanathan, a professor of English at St. Xavier's College, explained in a 2007 article, "many new, highly elitist schools and self-financing colleges have mushroomed in Ahmedabad in the last five years." In the resulting competition, "Jesuit institutions have lost something of their pre-eminent position."51

As Jesuit schools began to admit students from poorer backgrounds, they could no longer rely on the tuition fees of students from wealthier families; they could not remain self-financing. Practically all of the Jesuit schools in Gujarat adopted a policy of applying for grants-in-aid from the government. One official explained, "Salaries and maintenance fees are paid through government grants. Instead of collecting high fees from the students… we are able to get free education to the poor and needy."52 But government aid comes with strings attached. Grant-in-aid schools have to follow the Gujarat Board curriculum, use the Gujarat Board textbooks, and administer the Gujarat Board exams.53 The government also imposes its own conditions – and often takes its own time—in the appointment of new faculty.

The Gujarat Board Curriculum has a negative reputation. According to an article in the Economic Times of India, "Gujarat State Board of School Textbooks have over the years faced public criticism locally for their error-filled textbooks."54 Style is also a problem. Many of the textbooks are initially written in Gujarati, then translated into English for English medium schools.

One former student, a product of the Gujarati education system, explained, "of the various different boards, the Gujarat Board is considered to be the weakest. It has the easiest of exams compared to the ICSE and the CBSE boards." 55 In 1987, 75% of the Jesuit schools in Gujarat stayed with the Gujarat Board.56 The choice of Boards at the high school level has lasting effects since colleges consider the quality of the student's Board curriculum when making decisions on admission.57

Regarding the collective composition of the student body of the Jesuit schools in Gujarat, one school official stated, "Out of every five students, one will be a Catholic, one will be a minority, meaning Muslim or some other group, one will be a tribal, and one will be from some backward class. In short it is a very mixed group." The Jesuit schools in Gujarat largely have catered their admission policies toward these groups ever since General Congregation 32 of 1974.58 The only group that is not widely represented is students from wealthier families.

St. Xavier's College

|

|||

| Figure 6: In 2014, St. Xavier's College attained "autonomous" status, the first college in the state to achieve this distinction. Photograph courtesy of Howard Spodek. | |||

St. Xavier's College (Ahmedabad) was founded in 1955, initially as an Arts College. By the next year, the college also included classes in the sciences.59 St. Xavier's quickly rose to prominence among the colleges in Gujarat. Fr. Francis Braganza, one of the founders and first Vice-Principal, asserted that within the first seven years of the College's founding, "9 out of the top 10 (best students) came to Xavier's."60

As of 2019–20, 3,340 students were enrolled at St. Xavier's College, including 308 Catholics. 2,030 of the students are females; 1,618 males.61 The numbers have been rising steadily from 2103 in 2016; to 2558 in 2018; to 2989 in 2019.62 Much of the increase has come from the introduction of new courses of study, outside the usual curriculum, which now enroll 1073 of the 3,340 students.

Fr. Lancelot D'Cruz currently serves as in-charge Principal. In an interview, Fr. D'Cruz said that prior to General Congregation 32, St. Xavier's was "considered as an elite college. Basically, the richest people came here to study." As a result of General Congregation 32 and the "option for the poor," however, "in the early 80s, the college management made the decision that we will follow the reservation policy of the Indian Government."63 This "reservation policy" recognized that poverty and deprivation were often closely related to low caste status, or tribal status. In order to combat and overcome this caste and tribal discrimination, the government "reserved" a percentage of places in educational institutions, government employment, and elected positions for members of the lowest castes and tribes (people living in remote areas, usually outside the Hindu community). St. Xavier's decision to accept and follow the general reservation standards of the government coincided with debates – and violent riots – occurring within the society generally over the issue of extending the reservations to "other backward castes," groups not in the lowest castes, but not much above them.64

The decision at Xavier's was fraught. The College had a choice. The Indian Constitution exempts minority educational institutions from implementing these government reservations for disadvantaged groups.65 Considering that Christians make up only about two percent of the Indian population, Jesuit Schools fall under this definition of "minority institutions."66 Until the mid-1980s St. Xavier's College, as a minority educational institution, did not implement the government reservations. Father Fernando Franco, who studied at St. Xavier's College from 1969 to 1972, following his arrival from Spain, and taught at the College from 1977 to 1997, described the decision-making process during this transitional time between 1980 and 1985: "A group of young Jesuits … were at the College and we decided that a minority College, even if it was not forced to keep the rule of reservations, was going to start keeping the rule of reserving positions for students in the class belonging to SCs [Scheduled Castes] and STs [Scheduled Tribes]." This decision was met with much resentment and resistance. There was a "rebellion" among many of the College's faculty. According to Fr. Franco, "the main argument of the staff was, 'This is the best college in Ahmedabad—number one. You do this, and the quality of the college will go down.'"67

The College recognized that the new students who would be coming under the new admissions policy would require additional mentoring. "The Social Service League was started to cater to the poor and the marginalised in society. … Then we started the Jagrut [Awakening] Forum catering especially to the SC/ST/OBC [other backward class] students."68 For three years, this program was supplemented by a special program in Youth Leadership, in collaboration with Catholic Relief Services. Special care was also extended to the visually challenged,69 and the Social Service League provided these services as well. These programs included not only formal educational courses and exam preparation, but also special exercises in "character formation" including participation in drama and leadership activities to help overcome the damages of centuries of cultural as well as economic and political discrimination.70

Saroop Dhruv, with Hiren Gandhi, was in charge of the jagrut program. She elaborated on its activities: "personal counseling, open discussion sessions on social issues, such as casteism, communalism, patriarchy, theater training."71 She also noted that many of the Fathers helped in the students' assimilation to the college. Not all the lay professors, however, were so understanding. Some were openly dismissive. Dhruv reports that some of the new students told her that "the whole atmosphere at Xavier's, both students and faculty—although not the Jesuit Fathers—treated them like 'garbage.'" The Principal of the College at the time, Fr. Francis Parmar, reported:

more than 30% of our students belong to the Scheduled Castes, Other Backward Castes and Adivasis; … we also have 35 differently-abled students. … We are committed to giving the poor and the marginalized an opportunity to study and excel in the finest college in Gujarat.72

The results seemed effective. For the year 2005, St. Xavier's exam results were as follows, indicating the percentage of students successfully passing each degree course:

First Year (FY) BSc. 82%; Second Year (SY) BSc. 91%; Third Year (TY) BSc. 95%

FYBA 88%; SYBA 89%; TYBA 90%

MSc. 86%; MA 87%73

Despite some opposition, many Xavierites valued the diversity the new students brought to the college. Pratishtha Pandya, a student at St. Xavier's College from 1992 to 1995, and now a faculty member at Ahmedabad University, spoke positively of the results: "You saw a certain kind of diversity in your class… In terms of the kind of people who were with me, they came from different schools and different educational backgrounds as far as the families were concerned."74 Pandya did not think this kind of diversity was commonly found among the other colleges in Ahmedabad. Aara Patel, another former student, now holding a Ph.D. in genetics from University College London, attended St. Xavier's College from 2008 to 2011. When asked to identify what set St. Xavier's apart from other colleges in the city, she also praised the diversity of the student body.75

Prof. Suguna Ramanathan, who taught in Xavier's English department from 1970 to 2002, describes an overall change in orientation. She writes of the time she arrived:

That was an era so very different, replete with echoes of a colonial past, but also a simpler time, or so it seems now. …There was a great deal of stimulating conversation in the staff room about politics, the university, about literature, painting and philosophy.76

She mentions a group of a half dozen faculty outstanding for their intellectual concerns and productivity. "All of us somehow had more time in the 70s and 80s. … the students … too had more time. ... They … certainly read more."77 She continued her assessment:

The 70s turned invisibly into the '80s, and slowly changes in understanding began to come to me through the positions that the college took. It is here that I was made aware of an unjust social order, of the caste-ridden society in which we live, and of gender constructions long internalized and lived out without question. My older aesthetic preoccupations now gave way to a different perception of the world. I owe this growth to the college, to its own developing thrust in favour of the dispossessed, to the people I met here and from whom I learned a great deal.78

By the time she retired, in 2002, she wrote that "the work load had become considerably heavier, career advancement an issue, and the teaching burden had attendance strictly enforced. But also, there was participatory management, there were faculty seminars, many more staff members with PhDs and a much higher degree of professionalism. Some loss, some gain, but that is the nature of change."79

The new policies and their results were impressive, but not without their problems. The Siddiqui family have been associated with St. Xavier's College since 1964, spanning three generations. In a series of interviews, they spoke about their experiences at the college. Burhan Siddiqui taught psychology at St. Xavier's College for thirty-two years. He also joined Fr. Heredero in helping to establish the St. Xavier's Behavioural Science Centre. His sons and daughter, his daughter-in-law, and his granddaughter attended the College. More recently, however, the family has become somewhat disillusioned after observing what they felt was a sharp decline in the quality of education. Burhan specifically felt that the quality of leadership declined after the early years under Fr. Herbert de Souza – widely regarded as a charismatic and even flamboyant leader—who served as principal from 1956 to 1970. Siddiqui recalled that Fr. de Souza made it a point to remember by name each of the 1,500 students in the College at that time and that the students had a "love and fear of him." The standard of discipline under Father de Souza was very high in regard to dress code and behavioral issues. "That discipline has gone gradually." Siddiqui's daughter, who studied at Xavier's College in the mid-1980s, spoke of a lack of discipline in regard to attendance during her time there, specifically for classes in English.80 Several interviewees noted a disjuncture at the College between the quality of education in languages and the arts – which, they reported, declined sharply – and in the sciences – where St. Xavier's has consistently held a leading position. (To some degree St. Xavier's experience mirrors a drop in the standards of liberal arts education throughout Gujarat.81)

Reflecting on the changes, Burhan observed, "It has become mass education. The policy has changed. … Previously those who could afford it would come to the college. Now everybody is coming to the college, even those who do not want to study."82 He cited in particular the effects of competition from the increasing number of higher standard, self-financing private schools, which could offer more innovative curricula, as contributing to the decline of St. Xavier's elite status. Burhan's grandson, for example, who wanted to pursue a business curriculum, had to look elsewhere. The curricula at the self-financed institutions were more numerous, but also multiply more expensive, than those at Xavier's, which was a grant-in-aid institution. Many families with the money to afford them began to choose the self-financed colleges and universities.

Until 2014, the restrictions on offering innovative courses inhibited St. Xavier's ability to compete with the new self-financed colleges and universities. St. Xavier's College was affiliated with Gujarat University. As is the common pattern in India, the University controls the course syllabus and exams in exchange for financial support from the State. As Fr. D'Cruz, said, "We could do things only after gaining permission from [Gujarat] University… the exam is conducted by [Gujarat] University, the marks are given by [Gujarat] University."83

In 2014, however, St. Xavier's College attained "autonomous" status, the first college in the state to achieve this distinction.84 Although framed differently, the petition for a kind of "autonomy" dated back at least to a case before the High Court of Gujarat in 1974.85 A more recent, and formal, petition began in 2012 and was granted in 2014.86 The College can now establish additional course syllabi independent of Gujarat University; but these new courses must be self-financed. The government grant-in-aid does not cover the salaries of professors teaching these new courses offered under the autonomous structure. As a result, the College now offers six clusters of courses, two traditional clusters funded by grant-in-aid payments from Gujarat University; four self-financed under the rules of autonomy. The annual fee structures are dramatically different. First year fees are as follows: Grant-in-aid degree programs leading to the B.A. degree charge only Rs. 7385; to the B.Sc. degree, only Rs. 9985. On the other hand, self-financed programs leading to the Bachelor of Computer Application charge Rs. 31,685; to an MA in Psychology, Rs. 45,670; to a B. Com, Rs. 59,985; to the M.Sc., Rs. 70,100.87 (Fees in subsequent years are slightly lower in all the programs.) 1073 students are enrolled in the newer cluster of innovative, self-financed courses; 2267 are in the government grant-in-aid cluster of more traditional, university-mandated courses. Data were not available on the distribution of SC/ST/OBC students, nor of students of various income levels, across the various clusters. College authorities maintain that an abundance of extra-curricular activities, including sports, bring students together from across all six programs.

In-charge Principal Lancelot D'Cruz speaks today with pride in his College, remarking that, "Xavier's is the only College in Gujarat to be awarded a Five Star rating by the GSIRF [Gujarat State Institutional Rating Framework] for 2018–19 and we have been ranked number 56 in the country by the National Institutional Ranking Framework."88 Even prior to autonomous status, he points out, "Xavier's was accredited with Five Stars (in 2001), reaccredited with an A + (in 2007)."89 The weekly news magazine India Today, in its annual survey of "The Best Colleges of India," for 2019 ranked St. Xavier's College (Autonomous) Ahmedabad number 24 among all the Arts Colleges in India and number 20 among Science Colleges.90

Despite these high evaluations, and the new autonomous status, some observers raise concerns about Xavier's College's ability to continue to compete with the offerings of new, private, self-financed universities that are springing up in Ahmedabad today. They also question Xavier's ability to sustain a powerful program in the liberal arts when such programs almost everywhere are facing declining enrollments and scarcity of funding. Today for example, the College administrative office reports that in the grant-in-aid sections of the College two teaching posts are yet to be sanctioned by the state government in the arts division, 3 or 4 in the science division. The College exists, and thus far continues to flourish, in the context of massive change in India's systems of higher education. Its desire both to maintain standards of excellence and to open to students from deprived backgrounds has created tensions, but it has also opened new possibilities for social and economic diversity combined with quality education.91

St. Xavier's Loyola Hall

Fr. Joachim Vilallonga founded Loyola Hall in 1934 at its original location in Mirzapur, close to the historic center of Ahmedabad. The foundation stone for the current location of the school, in the semi-suburban Naranpura neighborhood of the city, was laid in 1956. Naranpura provided abundant room for expansion, a "30-acre campus surrounded with paddy fields."92 Initially, only the 8th to 11th standards (grades) were transplanted to the new location; in 1966 the primary school (which included kindergarten) was also relocated. 12th standard followed later. St. Xavier's Loyola Hall receives government grants in aid and follows the Gujarat Board; a number of its students come from educationally deprived backgrounds.

As of 2019, St. Xavier's Loyola Hall served 2,842 students, 370 of them Catholics. 1,781 of the students were boys; 1,061 were girls.93 Like St. Xavier's College, Loyola Hall had been considered an elite school until the early 1980s.94 The students of both institutions were "mainly the children of rich people."95 The high reputation of education at Loyola Hall in this early period—and the concern for its current status—are reflected in the following interviews and email communications.

Gaurav Shah entered the second standard at St. Xavier's Loyola Hall in 1971.He continued at the school through twelfth standard and graduated in 1981. Shah is currently the franchisee of Crossword Bookstores, part of a national chain, and the most important bookstore specializing in English language books in Ahmedabad. In an interview,96 he spoke warmly of his time at Loyola Hall. When asked why his parents enrolled him at the school, Shah replied, "I think it was primarily because it was one of the better English medium schools in Ahmedabad. Most of the other schools were Gujarati medium." In India, English has traditionally been the language of the educated. It is the link language among all the regions and languages of the country and the principal language of international communication.

Shah had warm memories of his time as a student. "I think a lot of kids that went to Xavier's during our time were really fortunate. Some of the teachers—like Father Morondo, Father Erviti—these guys were people who actually taught a lot of wonderful courses. They built character in their students." But Shah made a clear decision not to send his own children to Loyola Hall. The School had changed:

During our times, i.e. 1971 onwards, the St. Xavier's Loyola School gave admissions intentionally to students of all classes & creeds, all religions, the rich as well as the poor. They created a secular mix in each class … and there was not much distance internally between the students. … In the last four decades, not only have the government policies changed, not only have the school policies changed, but most importantly the gap between the rich and poor has grown so wide, not only in terms of the monetary gap but also the social divide gap, that now parents of so-called rich children do not want their children to mix with the poor children. Slowly as a society we have demolished and destroyed the secular social fabric of society.97

In addition, the faculty had changed. "The Spanish Fathers moved away, and the Indian Fathers put in their place lacked similar commitment." Shah sent his children to be educated elsewhere, in a school which taught to the National Board of ISCE. 98

Fr. Sunny Jacob, the current head of the Jesuit Educational Association of South Asia, and an Indian-born Jesuit himself, reflected on the changing demographic composition of the Jesuit order in India. The Indian Jesuit Schools "started with German Fathers in Gujarat, then Spanish Fathers in Gujarat, Belgians in Ranchi, Americans in Jamshedpur… The institutions in the provinces were initiated by people from abroad."99 By 1989, however, roughly 89% of the Jesuits in India were native born Indians. Almost a fourth of the entire Jesuit order now live in South Asia, about 270 of them in Gujarat.100 Fr. Jacob continued: "Economically, [the Indian-born Jesuits] are not coming from well-to-do families. This is all affecting the quality of education." He insists the issue is not racial or ethnic. The native-born Indian Jesuits are not receiving as high a level of education in India as had the Jesuits coming from more developed countries although, as several informants pointed out, many of the European Jesuits – like Fr. Franco – came as young men who ultimately completed the final stages of their higher education in Indian institutions.

Abhijit Kothari, a business owner in Ahmedabad, is also an alumnus of Loyola Hall. He began in kindergarten in 1969 and continued through the twelfth standard. Like Shah, Kothari mentioned that one of the main reasons his parents enrolled him at the school was its English medium instruction. He spoke very warmly of his time at Loyola Hall and of the Spanish Jesuits who taught him during his thirteen years there. Reflecting on the Spanish Fathers, Kothari said, "To think that they left their country to come and spend almost their entire life in India to teach students… It's a different level of commitment than a teacher who may be doing the best that he or she can but is essentially doing it to earn a salary."101

Kothari felt that students who came out of Loyola Hall seemed to have "a little extra something," perhaps because they entered the school with higher social and cultural capital, but also because the emphasis of the schooling was not solely on "getting a good grade or getting a good rank."102 Kothari's statement is consistent with the Jesuits' "Ignatian Pedagogic Paradigm" of teaching values and goals that shape students morally in addition to giving them the tools to succeed professionally. In regard to the discipline at Loyola Hall, Kothari noted that cutting class was not something that happened very often in his day. When asked if he would send his own children to Loyola Hall, however, Kothari said, "The one factor that would go against St. Xavier's [Loyola Hall] would be the fact that they continue to operate within the Gujarat Board."103 During his own time at Loyola Hall, there was more variety in the textbooks and curricula that were used in the classroom. He sent his daughter to a different school.

The current principal of St. Xavier's Loyola Hall, Fr. Charles Aruldass, spoke not only of the decline in the number of foreign Jesuits; the number of Indian Jesuits has also declined. During the 1985–86 school year, there had been seven Jesuits on the staff of Loyola Hall.104 Currently, Fr. Charles is the only Jesuit teaching there. This decline in numbers reflects the shrinking of the Jesuit order worldwide. It also reflects a decision to extend the benefits of Jesuit education to the poor by establishing schools in remote areas including the tribal belt of south Gujarat and zones of "socially and economically weaker sections" of population in north Gujarat. Today Gujarat state hosts eighteen primary and secondary Jesuit schools: four are urban, including Ahmedabad and adjacent Gandhinagar; four semi-urban; ten rural.105 Each is headed by a single Jesuit priest, thus absorbing faculty that might otherwise have been available to the urban institutions, like Loyola Hall.106 The camaraderie that characterized the array of Jesuit faculty at Loyola Hall in the 1970s and 1980s – and extended to their students—is gone.

Student attendance has become an issue. Families of the students have received emails from the School reminding them that attendance is mandatory. One problem is the entrenched practice of "private tuition." Teachers, individually and in collective private enterprises, offer private and group sessions outside the classroom to students who can pay for them. Different from the "coaching" that often helped individual students in previous years to make up for their classroom deficiencies, many of the current "tuition classes" prepare students to take specialized exams that will get them into better colleges and specialized training programs, which are largely beyond the scope of the Gujarat Board exam.107 The institutions offering "tuitions" are essentially small, private schools operating outside the official system. They advertise precisely this service. For example:

Over 17 years of experience in the industry enable us to develop the most efficient set of strategies made with the purpose of achieving targeted band scores in IELTS, PTE and TOEFL. Find Top IELTS Coaching in Ahmedabad. It has 10000+ happy students and more than 95% students have achieved their desired bands in IELTS exam in the first attempt.108

They represent one aspect of the privatization of education.

The rise of full scale private schools in Ahmedabad has also impacted the composition of Loyola Hall's student body. As one faculty member remarked, "Private schools have mushroomed, and they charge exorbitant fees which we do not charge… ultimately, we are not catering to the rich, we are catering to the working class, middle class, average, and below average." He noted that tuition is modified for poor students on a case-by-case basis so that some can afford to attend. The combination of the Jesuit "option for the poor," with the rise of self-financing private schools competing for wealthier students, has shifted the demographics of the student body in the Jesuit schools. Many wealthier, upwardly aspirational families now look elsewhere. Geography may also be an issue. Suburbanization, especially of wealthier families, takes them ever further towards the western suburbs of Ahmedabad. They may look for schools for their children closer to their new residences and new neighbors.

Government intervention in teacher selection also poses problems. From the 9th to 12th standards, the teachers' salaries are paid by the government, and government funding comes with its own rules and regulations.109 Teachers who are appointed must be approved by the state government. The process is time consuming and, as noted above in regard to government aided colleges, it has sometimes left the School temporarily without teachers for certain classes.

The change over time at St. Xavier's Loyola Hall is clearly visible. The School, once considered elite, was praised by its former students. Many of these same former students, however, did not enroll their own children in today's Loyola Hall. The School's reputation has declined. The school now caters its admission policies to less well-off students and accepts government funding for its teachers' salaries. The school's use of the Gujarat Board curriculum and exams has dented its reputation especially as compared with newer private self-financing schools that follow higher quality Boards. Lastly, the diminishing of the Jesuit presence on the faculty and administration has lowered the school's educational quality.

To end on a more positive note, a conversation with four past presidents of the St. Xavier's Loyola Hall alumni association did present a much brighter picture. These four men, who had studied at Loyola Hall between 1968 and 1988, had sent their own children to Loyola Hall; they found the Gujarat Board adequate for their children to gain admission to good colleges; they praised the values orientation and character formation that mark Loyola Hall's stated mission; and they spoke highly of extra-curricular activities at Loyola Hall, especially sports and school celebrations – the kinds of activities that they, as alumni, help to sponsor.110 A discussion with a former student at Mt. Carmel School, a nearby Christian, but not Jesuit, high school, also noted the abundance of extra-curricular activities at Loyola Hall. They attracted the participation of students from other schools then and they still do. They are a reminder that Loyola retains among its loyal family and students many who are attracted, as Fr. Aruldass maintains, by its emphasis on developing "character and personality through graded responsibility, personal guidance and social awareness" following from "the spiritual vision of Ignatius [Loyola]."111

Conclusions

Jesuit schools and colleges in India have changed dramatically from the days of St. Francis Xavier, for whom many are named, and even from the days of British Raj. The greatest changes have come following the Second Vatican Council, 1962–65, as Catholic educational institutions worldwide were called to become more inclusive of the poor. General Congregation 32, which began in 1974, further stressed the importance and priority of directly serving the poor in all Jesuit missions. National Seminars convened by the Jesuit Educational Association of India conveyed this mission explicitly to India. This policy was embraced by many of the elite Jesuit schools in India. Educational institutions like St. Xavier's College and St. Xavier's Loyola Hall in Ahmedabad modified their admission policies and their outreach programs.

New directions come from not only from within the Church and the Jesuit order, they also resulted from a recognition that, in a post-colonial world, schools and colleges had to serve new clientele with their new responsibilities and new aspirations. As a result of tending to these new mandates and new students, many Jesuit Schools in India struggled with their finances; they could no longer rely on the tuition payments from students of wealthy families. They became much more reliant on government. Many applied for Government aid. In exchange, however, they had to follow strict State Board curricula and testing that are widely considered to be inferior to National Board standards. State curricula, even when taught in English, were usually (poor) translations from textbooks originally written in local languages, like Gujarati. Government grants in aid also stipulated that the government must sanction and approve all faculty hires, but in many cases new appointments were delayed or not approved, leaving faculty strength reduced.

The more than fifty per cent decline in the number of Jesuits worldwide, coming at the same time as the order's wish to expand its schools into more rural areas, has also affected staffing. Loyola Hall, for example, currently has only one Jesuit on its faculty, its principal, Fr. Charles Aruldass. Jesuit priests who previously might have been assigned to Loyola Hall, or one of the other Jesuit urban or semi-urban schools, are instead serving in tribal regions of south Gujarat and impoverished areas of the northern part of the state. So, Loyola Hall is understaffed and limited in its capacity to innovate.

Meanwhile, in the 1990s, India's new economic policy promoted liberalization, allowing for the establishment of many elite, expensive, self-financing private schools. These self-financing private schools were attractive to wealthy families because they were not beholden to the government; they taught a more sophisticated curriculum, usually in English; and they had the additional funds with which to pay higher salaries to their teachers, whom they could appoint without government interference. These schools challenged, and in some cases overtook, some of the elite Jesuit schools and their once prestigious position.

The 1990s also brought increasing prominence to the ideology of militant Hindutva. Many of the Jesuits working in the educational mission in India stated that they felt a sense of intense scrutiny and vulnerability. In earlier times, not only was the threat of Hindutva less evident, but the elite alumni of the Jesuit elite schools could and did protect their former colleges, schools, and teachers from pressures and threats, sometimes coming from the government, in ways that may not be available to the less elite graduates today. The result is somewhat greater stress and self-censorship on the part of the faculty and administration. This apprehension and self-censorship are evident today across Indian public life.

St. Xavier's College and St. Xavier's Loyola Hall serve as specific examples of some of the broad changes affecting all of Indian education and Jesuit education in particular. In the 1980s, St. Xavier's College changed its admission policies to be more open to the poor, the scheduled castes and tribes and "Other Backward Castes" choosing to implement the Indian policies of "reservation" and align with the Jesuit principles of General Congregations 32. Some of the lay teachers resisted this change; they believed that the acceptance of poorer students into the College would eventually bring down the quality of education. In practice, however, many students from traditional backgrounds welcomed the greater diversity of the expanded student body. The College's attainment of "Autonomous" status in 2014 has opened possibilities of creating new programs and hiring new faculty, enabling the College, at least thus far, to compete with new self-financed private colleges and universities that have been steadily expanding.

As the Jesuits have implemented the mission to the poor in part by establishing schools in remote areas of Gujarat, each staffed by a single Jesuit priest, St. Xavier's Loyola Hall, once staffed by a dedicated core of Jesuits, now retains only one Jesuit faculty member, the principal. Obliged to follow the Gujarat Board Curriculum, it also cannot compete for wealthier students with some of the new self-financed schools that mark the privatization of education throughout India. Its teaching mission is also undercut by the rise of an array of private institutions offering "tuitions," special classes geared to the entrance exams at prestigious colleges, vocational institutions, and overseas study. In this India-wide phenomenon, students take attendance at their "tuitions" more seriously than at their degree-granting schools. Principal Fr. Aruldass laments not only the competition for his students' attention, but also, as he sees it, the decreasing regard for the "Ignatian Pedagogical Paradigm," the Jesuit mission of holistic moral education that goes beyond knowledge for the sake of taking exams.

To understand the evolution of Jesuit education in India over the past half century, and to understand the pivotal position of Fr. Erviti in his thirty years in Ahmedabad, 1956–86,—the starting point for this study—we have gone back to see the original goals of the Jesuits in Portuguese India, and their transformation in British India. Then we have considered more recent, and less comprehensively studied, perspectives that have been global – decisions of the Vatican; international – decisions of the General Congregations; national – decisions of the Jesuit Education Association; again national – the educational and the economic policy decisions of the Government of India; statewide – educational Board decisions and funding decisions of the Government of Gujarat and Gujarat University; local—developments of private formal educational institutions and private tuitions. We have considered the changing ideological orientations of the Catholic Church and their intersection with various waves of Indian nationalism including Hindutva. We have considered the changing demographics of the Jesuit order in terms of shrinking numbers and changing national origins and migrations. We have considered the changing values of the two local schools that we have examined in detail, including the strategies of the priests who administer and teach in them, and the wishes of parents and students who have chosen to attend them – or not. We have considered briefly the developing concern with informal education. We have seen the world in these two local educational institutions in Ahmedabad and these two institutions in the world.

This preliminary assessment has been written by two historians of American origin; it calls out for much further research on the continuing evolution of Jesuit education in India—and around the world—by scholars of additional disciplines and additional nationalities.112

Luke Sullivan completed his Bachelor's degree at Temple University, Philadelphia, in December 2019, with a double major in History and Education.

Howard Spodek is Professor of History, Temple University. He is the author of The World's History (Hoboken, NJ: Pearson, 5th ed., 2015); Ahmedabad: Shock City of Twentieth Century India (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2011; New Delhi: Orient Blackswan, 2012); and is Executive Producer of "The Urban World," https://vimeo.com/158639745 password: Ahmed

1 Howard Spodek, Rajeev Chakranarayan, SJ, and Vanessa Nazareth-Dalal (eds), Creating Citizens: Fr. Ramiro Erviti in Ahmedabad, India, 1956–86 (Ahmedabad: St. Xavier's Social Service Society, 2017)

2 One recent book does provide an overview: Thomas Banchoff and José Casanova, eds., The Jesuits and Globalization: Historical Legacies and Contemporary Challenges (Washington: Georgetown University Press, 2016).

3 During the counter-reformation in the early 1500s, "the spirit of evangelization began to take Asia into its sphere. St. Francis Xavier was the embodiment of that spirit and for a short period, following his example, there was a great movement to convert the heathen in Asia." K.M. Panikkar, Asia and Western Dominance; a Survey of the Vasco da Gama Epoch of Asian History, 1498–1945 (London, George Allen & Unwin, 1953), 15.

4 Gregory, Naik, SJ, Jesuit Education in India. (Anand: Gujarat Sahitya Prakash 1987). 5–6.

5 Panikkar, Asia and Western Dominance, 386.

6 Panikkar, Asia and Western Dominance, 385.

7 Leonard Fernando. Jesuits in India (Oxford Handbooks Online). Available at https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199935420.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199935420-e-59. Accessed March 15, 2019.

8 Ibid. An earlier mission had been founded in Bengal in 1834 but closed in 1846.

9 Ibid.

10 "Catholic Education in India," The Catholic World, Vol. 57, no. 387 (June 1897), 303, Available at https://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/moajrnl/bac8387.0065.387/313:1?page=root;size=100;view=image. Accessed March 15, 2019.

11 "The Catholic World," 299–300.

12 "The Catholic World," 303.

13 Felix Plattner, The Catholic Church in India: Yesterday and Today (India: St. Paul Publications, 1964), 6–14.

14 Ibid.

15 Society of Jesus, online http://www.catholic-hierarchy.org/diocese/dqsj0.html

16 Curia Generalis, Society of Jesus (10 April 2013). "From the Curia – The Society of Jesus in Numbers," Digital News Service SJ. The Jesuit Portal – Society of Jesus Homepage. 17 (10). Available at https://jesuitportal.bc.edu/research/documents/

17 Gellért Merza, Discovering Jesuit Schools in India. Educate Magis. Available at https://www.educatemagis.org/blogs/discovering-jesuit-schools-india/ (Accessed April 20, 2019)

18 Ibid.

19 K.M. Panikkar, Asia and Western Dominance; a Survey of the Vasco da Gama Epoch of Asian History, 1498–1945 (London, George Allen & Unwin, 1953), 15.

20 Ambrose Pinto SJ, "The Achievement of the Jesuit Educational Mission in India and the Contemporary Challenges it Faces," International Studies in Catholic Education Vol. 6, Issue 1 (2014), 14–32.

21 John W. Padberg (ed.), Jesuit Life & Mission Today: The Decrees & Accompanying Documents of the 31st–35th General Congregations of the Society of Jesus (St. Louis, MO: Institute of Jesuit Sources, 2009, General Congregation 31, Decree 28, "The Apostolate of Education," 168–176 [495–546].

22 Ibid.

23 Naik, Jesuit Education in India,145.

24 Naik, Jesuit Education in India,152.

25 Naik, Jesuit Education in India,160.

26 Jesuit Education in India and Nepal: JEA Evaluation Report, October 1994, Education Case, Jesuit Education Society Secretariat Archives, New Delhi, India.

27 Fr. Herman Castelino, ed. Jesuit Education in the Third Millennium, Present Challenges, Future Priorities: Proceedings of JEA Triennial, May 14–17, 2003. Held at the Pedro Arrupe Institute, Raia, Goa. (Anand: Gujarat Sahitya Prakash, 2003), Sneh Jyoti Library, Sevasi.

28 Nahla Nainar, "Including the Excluded," The Hindu, March 11, 2016. Available at https://www.thehindu.com/features/metroplus/society/including-the-excluded/article8341815.ece. Accessed May 31, 2019

29 See Secretariat for Jesuit Social Action at https://jcsaweb.org/ministries/social-action/. Accessed March 15, 2019.

30 Howard Spodek, Rajeev Chakranarayan, and Vanessa Nazareth-Dalal, (eds), Creating Citizens: Fr. Ramiro Erviti in Ahmedabad, 1956–86 (Gujarat, India: St. Xavier's Social Service Society, 2017).

31 Paolo Freire. Pedagogy of the Oppressed (New York: Continuum, 2000)

32 J.M. Heredero, with P.T. Contractor and B.B. Siddiqui. Rural Development and Social Change: An Experiment in Non-formal Education (New Delhi: Manohar, 1977); J.M. Heredero. Education for Development: Social Awareness, Organisation and Technological Innovation (New Delhi: Manohar Books, 1989); and Howard Spodek personal e-mail with BSC, 8 June 2019.

33 Joseph Valiamangalam, "History of Jesuits in Gujarat," accessible at https://sites.google.com/a/jesuits.net/websites-blogs-of-gujarat-jesuits-insitutions/history-of-gujarat. Accessed May 31, 2019.

34 See http://hdrc-sxnfes.org/about-us.aspx. Accessed May 31, 2019

35 For additional initiatives in Vallabh Vidyanagar, Surat, Modasa, Songadh, in and around Vadodara, and in Ahmedabad, see Valiamangalam, at https://sites.google.com/a/jesuits.net/websites-blogs-of-gujarat-jesuits-insitutions/history-of-gujarat. Accessed May 31, 2019.

36 John W. O'Malley, "Historical Perspectives on Jesuit Education and Globalization," In Banchoff and Casanova, eds., The Jesuits and Globalization, 162

37 Naik, Jesuit Education in India, 64.

38 Interview with Father Sunny (current Head of the Jesuit Educational Association of South Asia), conducted by Luke Sullivan in New Delhi, India, January 3, 2019. Father Jacob mentioned that there have been fewer National Seminars in recent times since the Jesuit Educational Association of India became the Jesuit Educational Association of South Asia ten years ago. The process of reorganising the Provinces of South Asia is ongoing, and so also the Secretariats.

39 "Public Schools" in India are, confusingly, what Americans would consider Private Schools, hence the authors' use of "so called" in the article. In urban India, Municipal Schools would be the equivalent of American Public Schools.

40 K.S. Chalam. Economic Reforms and Social Exclusion: Impact of Liberalization on Marginalized Groups in India (New Delhi: Sage, 2011), 166.

41 Banchoff and Cassanova, The Jesuits and Globalization, 2.

42 Barbara Metcalf and Thomas Metcalf, A Concise History of Modern India (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 3rd ed., 2012), 274–277.

43 Despite pressure from many Hindutva leaders, a Hindu Temple has not yet been built on the location for fear of further communal violence.

44 The literature is abundant. For a recent outstanding contribution, see Angana P. Chatterji, Thomas Blom Hansen, Christophe Jaffrelot, eds. Majoritarian State: How Indian Nationalism is Changing India (London: Hurst & Co., 2019). For an earlier account, focusing on Christians in Gujarat, see J. Valiamangalam, "Gujarat: The Hindutva Laboratory and the Christian Response," In the Shadow of the Cross: Christians and Minorities in India Encounter Hostility, (Mumbai, St. Paul Press, 2002), 108–134.

45 "Gujarat has been made the laboratory of Hindutva after the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) came to power in 1998 elections. Widespread violence against Christians and Christian institutions such as churches and schools took place from 1998 onwards…. In the Dangs District, the Hindutva forces burned down some Protestant churches, damaged the Deep Darshan school run by the Sisters at Ahwa, burned the Jeep of Fr. Antony Maila, S.J. and set fire to the boarding school," See Joseph Valiamangalam, "History of Jesuits in Gujarat," at https://sites.google.com/a/jesuits.net/websites-blogs-of-gujarat-jesuits-insitutions/history-of-gujarat. Accessed May 31, 2019.

46 The literature on 2002 is immense. See, for example, the summary in Spodek. Ahmedabad, 260–64.

47 Most recently, for example, see the video produced by the New York Times, "Modi Denies India Is Targeting Muslims. We Found a Different Reality," April 4, 2020, available at https://www.nytimes.com/video/world/asia/100000006963057/modi-muslims-india-citizenship-test.html. Accessed May 31, 2019.

48 For a history of the arrival of Jesuit missionary organization in the Gujarat region, beginning in 1893, see Joseph Valiamangalam, "History of Jesuits in Gujarat." Available at https//sites.google.com/a/jesuits.net/websites-blogs-of-gujarat-jesuits-insitutions/history-of-gujarat. Accessed May 31, 2019. Gujarat formally became a state only in 1960; until then the region was part of the greater Bombay Presidency, under the British, and then Bombay State after independence.

49 Naik, Jesuit Education in India, 178.

50Interview with an official who wished to remain anonymous, conducted by Luke Sullivan in Gandhinagar, India, January 2, 2019.

51 Suguna Ramanathan, "Jesuits in Gujarat: Looking Back Looking Forward," in Jesuits in India: History and Culture (2007), 15.

52 Interview with an official who wished to remain anonymous, conducted by Luke Sullivan in Gandhinagar, India, January 2, 2019.

53 High Court of Gujarat, Judgement decided on October 4, 2013. Available at http://www.the-laws.com/Encyclopedia/Browse/Case?CaseId=203102366200. Accessed May 31, 2019.

54 Dutta, Vishal. "Gujarat's School Textbooks Replete with Bloopers; Poor Translation to Blame" Economic Times of India, August 3, 2013 at https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/topic/Bloopers/news/2/2. Accessed May 31, 2019.

55 Interview with student who wished to remain anonymous, conducted by Luke Sullivan at Ahmedabad, India, December 29, 2018.

56 Gregory Naik SJ, Jesuit Education in India, 58.

57 Interview with student above at note 55 who wished to remain anonymous, conducted by Luke Sullivan at Ahmedabad, India, December 29, 2018.

58 Suguna Ramanathan, "Jesuits in Gujarat: Looking Back Looking Forward," in Jesuits in India: History and Culture (2007), 16.

59 Vincent Saldanha, "St Xavier's College Community," in Hedwig Lewis, ed., Jesuit Mission Gujarat (Gujarat: Gujarat Sahitya Prakash, 2014), 60.

60 Radhika Chhotai, Chinar Shah, "Young at 84: An Interview with Bishop Francis Braganza," in St. Xavier's College, Ahmedabad: Celebrating Fifty Years of Academic Excellence (Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India: St. Xavier's College, 2005), 49.

61 Gujarat Province Catalogue, 2020 (in press).

62 Gujarat Province Catalogue, annual.

63 Interview with Fr. Lancelot D'Cruz (Current Vice Principal of St. Xavier's College), conducted by Luke Sullivan in Ahmedabad, India, January 7, 2019.

64 For a general discussion of these issues, see Ramachandra Guha. India after Gandhi: The History of the World's Largest Democracy (London: Macmillan, 2007) 605–21. See also, Christophe Jaffrelot, India's Silent Revolution: The Rise of the Low Castes in North Indian Politics (Delhi: Permanent Black, 2003).

65 Article 30 states, "All minorities, whether based on religion or language, shall have the right to establish and administer educational institutions of their choice."

66 Indian Constitution, art. 30.

67 Interview with Fr. Fernando Franco, Instructor [retired] at St. Xavier's College, Ahmedabad, 1977–1997), conducted by Luke Sullivan via Skype from Elkins Park, Pennsylvania to Ahmedabad, Gujarat, November 15, 2018.

68 Vincent Saldanha, "St Xavier's College Community," in Hedwig Lewis, ed., Jesuit Mission Gujarat, 61–62.

69 Vincent Saldanha, "St Xavier's College Community," in Hedwig Lewis, ed., Jesuit Mission Gujarat, 61.

70 Ishwar L. Mehra, "Jaagrut," in St. Xavier's College, Ahmedabad Celebrating Fifty Years of Academic Excellence, 30–31,

71 Interview with Saroop Dhruv, conducted by Howard Spodek, Ahmedabad, July 29, 2019.

72 Fr. Rappai Poothokaren, "An Interview with Fr. Francis Parmar, S.J.," in St. Xavier's College. Celebrating Fifty Years of Academic Excellence, 2006), 96.

73 Francis Parmar, "Uchch Shikshanni Sewama Ardhi Sadi" (A Half Century in the Service of Higher Education) in St. Xavier's College. Celebrating Fifty Years of Academic Excellence, 11.

74 Interview with Pratishtha Pandya (former student at Xavier's College from 1992–1995), conducted by Luke Sullivan at Ahmedabad, India, January 10th, 2018.

75 Interviewed by Luke Sullivan at Ahmedabad, India, January 11, 2018.

76 Suguna Ramanathan, "Such Were the Joys," in St. Xavier's College. Celebrating Fifty Years of Academic Excellence (Ahmedabad: St. Xavier's College, 2006), 55.

77 Ibid.

78 Ibid.

79 Ibid.

80 Interviews with the Siddiqui family conducted by Luke Sullivan in Ahmedabad, India, January 2, 2019.

81 Interview with Fr. Fernando Franco, conducted by Howard Spodek, Ahmedabad, July 18, 2019.

82 Interview with Burhan Siddiqui, conducted by Luke Sullivan at Ahmedabad, India, December 29th, 2018.

83 Interview with Fr. Lancelot DeCruz (currently Acting Principal of St. Xavier's College), conducted by Luke Sullivan in Ahmedabad, India, January 7th, 2019.

84 For a discussion of the administrative problems of government colleges, and the benefits of autonomy, see Pankaj Chandra, "Governance in Higher Education: A Contested Space (Making the University Work)," in Devesh Kapur and Pratap Bhanu Mehta, eds. Navigating the Labyrinth: Perspectives on India's Higher Education (Hyderabad: Orient Blackswan, 2017), 235–264. For the rules and regulations of gaining autonomous status, see University Grants Commission. UGC Guidelines for Autonomous Colleges 2017. Available at https://www.ugc.ac.in. Accessed May 31, 2019.

85 In a petition produced under article 32 "the petitioner contended that as religious and linguistic minorities they had a fundamental right to establish and administer educational institutions of their choice as also the right to affiliation." See https://indiankanoon.org/doc/703393/. Accessed May 31, 2019.

86 For final disposal of the actual case that finally went through the Gujarat High Court from 2012. See http://gujarathc-casestatus.nic.in/gujarathc/# "In the High Court of Gujarat at Ahmedabad Special Civil Application No. 6158 of 2012." Accessed May 31, 2019.

87 See https://collegedunia.com/college/4969-st-xaviers-college-ahmedabad/courses-fees. Accessed May 31, 2019.

88 See https://sxca.edu.in/principals-desk/. Accessed May 31, 2019.

89 Ibid.

90 India Today, Special Issue, May 27, 2019. In both cases, its "perceptual score" was much higher than its "objective score." On the basis of 1000 points, it was 913.1 "perceptual" versus 576.7 "objective" among arts colleges; 931.1 "perceptual" versus 627.0 "objective" among science colleges. This discrepancy was generally true for almost all of the 50 most highly ranked colleges in both arts and sciences, but it was greater for St. Xavier's than for most.