FORUM:

Diffusion, Comparisons, and Periodization in the Pre-modern World

The Axial Age and Epic Literature: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Interrogating Historical Parallelisms for the World History Classroom

Joseph M. Snyder

|

|||

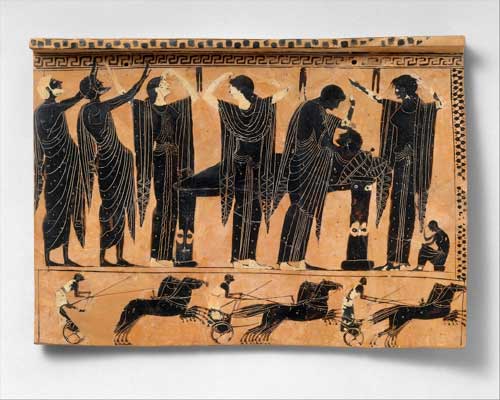

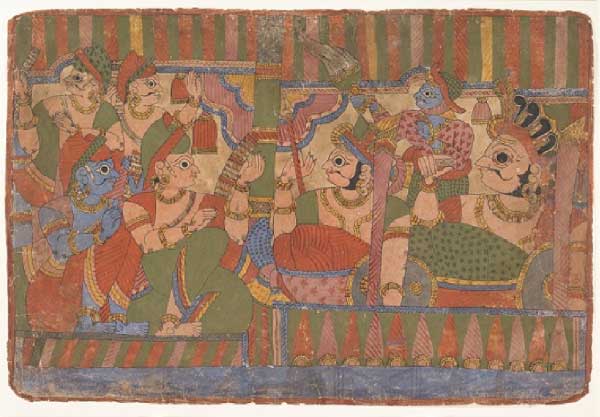

| Figure 1 (left): "The Trojans Repulsing the Greeks." Engraving by Giovanni Battista Scultori (1503–1575).1 Figure 2 (right): "Council of Heroes." Page from a dispersed Mahābhārata. Maharashtra, India ca. 1800.2 | |||

Throughout ancient history, there have been circumstances where interconnectedness and integration have not been present and yet civilizations thousands of miles apart have produced cultural goods, such as literature, that are remarkably similar. It is this phenomenon, referred to as "historical parallelism," which is the central focus of this paper.3 It takes as its point of departure the Axial Age, which Karl Jaspers argued was the "axis in world history . . . which has given birth" to everything that followed.4 To bring these themes to life in the world history classroom, several active-learning exercises are offered in the appendices to this essay, including a virtual archaeological "dig" with field log, "A Geography of the Axial Age" with guided debate prompt, and a table for comparing Axial Age civilizations with recommended readings.

The Axial Age refers broadly to a period beginning around the 9th century BCE which witnessed similar socio-cultural efflorescence across several great civilizations in various parts of the world, including Greece, China, Persia, Israel, and India. The processes inherent to the Axial Age unfolded at varying intervals and to varying degrees over the course of the ensuing several centuries. The multiplicity of world histories that resulted has proven rich territory for historical inquiry, particularly those interested in comparative analysis, itself the basis of this study.5 Centered on ancient Greek and Indian epic literature, this study is concerned with a comparison of the Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, with the Indian epic, the Mahābhārata. On the one hand, this paper is designed to provide instructors with a framework for challenging Ancient World History students to develop an understanding of the significance of the Axial Age, so often barely a footnote in most World History courses. Through comparison, students are encouraged to develop an appreciation for how ancient literature can provide insight into the societies that produced it—from gender roles and religious belief systems to societal mores and values—and the circumstances that prompted them to respond in similar ways. On the other hand, it is also a critical assessment of those similarities and argues that, unlike trade-based cultural diffusion, such similarities are not because one civilization has directly (or indirectly) influenced the other. Rather, the argument is made that the Homeric epics and the Mahābhārata reflect two societies going through approximately analogous stages of development.

The historical parallelisms which are an important characteristic of the Axial Age are the focus of this study. It is concerned with a specific instance of this phenomenon during the period: the transmission and writing down of Homer's Iliad and Odyssey and the Vedic Mahābhārata. All are cornerstones of classical civilizations; all were originally part of oral traditions that nostalgically look back to a "golden age"; all are concerned predominantly with military matters and the acts of gods and heroes; and all were not finally written down until centuries after the events they describe.6

Focus on the Greeks

For the ancient Greeks, the Iliad was arguably the most important and influential of the Homeric epics, despite the impression given by the enduring popularity of the Odyssey in schools today.7 Originating as a basic outline among the peripatetic bards of the Greek Dark Ages (ca. 12th century-9th century BCE), the Iliad was a composite, only finally arranged and written down during the tyranny of Pisistratus in the mid- to late-6th century BCE.8 Until that time, storytellers traveled from village to village, recounting the basic outline and then improvising by combining stock phrases with new material. These stories went unwritten because the Greeks of the Dark Age were illiterate, having lost the ability to read and write following the collapse of Mycenaean civilization ca. early-12th century.9 As a result of this oral tradition, Dark Age Greeks produced myriad variants of the essential story, itself concerned not with events of their own day, but rather the Trojan War, which evidence suggests occurred during the late-Mycenaean Age.

By the end of the centuries-long Dark Ages and the advent of the Archaic Period (ca. 800–500/450 BCE), when the Greeks reacquired literacy, the Mycenaean Age had taken on an aura of gloriousness. It was imagined in the Greek consciousness as a golden age peopled by heroes transformed into mythical, larger-than-life figures whose names are now familiar to modern students: Achilles, Hector, Paris, Priam, and Agamemnon, figures whose lives were "devoted to winning glory; and [the Iliad] represents with wonder their strength and courage."10 Their actions and conduct as detailed in the Iliad can and has been seen as a paradigm for behavior in the ancient Greek world. As Jaeger and Adkins have observed, the ethical values on display in the Iliad reflected the "cultural ideal" of ancient Greek civilization, an aspirational model upheld by the twin pillars of "honor" (Gr. Timē) and "worth" (Gr. Aretē).11 Together, these variables constitute familiar formula: where aretē refers to the combination of qualities for which Homeric heroes were admired (that is, physical strength, courage, daring, and success in battle) and timē mirrors the honor or recognition due a hero by virtue of his aretē.12

|

|||

| Figure 3: Achilles and Hector duel on horseback. Engraving by Sebald Beham (1500–1550).13 | |||

As this suggests, one of the important characteristics of the ancient world revealed in the Iliad is intense competition (Gr. Agon). A recurrent theme of Homer's epic is rivalry, as characters jockey for position to show their dominance and "intracommunal strife arises" when a warrior feels that his contribution has "not been adequately recognized."14 Evidence of this dynamic is prevalent in the Iliad, from Achilles' and Agamemnon's struggle over Briseis, to Paris' and Menelaus' rivalry over Helen, and, more broadly, the base competition between the two societies themselves. For Cook, the competitive dynamic motivating much of the action in the Iliad constitutes the Homeric society structure,15 reflecting certain contemporary sensibilities of Archaic Greek society as expressed in everything from the Greeks' annual games and public festivals (during which rhapsodes often competed against each other in recitations of the Homeric epics16) to the violence between city-states as they vied for supremacy in the Greek world.17

Students find these characteristics of the Iliad familiar, since they have featured extensively in popular culture, but it is worth emphasizing that the competition in the story mirrored many aspects of Greek life in the Archaic Period, if only to ground the actions described by Homer in some ancient reality. Likewise, the transmission of the Iliad transpired at a fruitful time in ancient Greek political advancements. For the Archaic Period witnessed the development and evolution of the polis, the Greek city-state and nucleus of ancient Greek politics. It was a revolutionary age, during which the Greeks reckoned with the ultimate expression of political independence in a highly competitive context. Here again, this development finds a parallel in the Iliad, an essential theme of which is the obligations between individuals and their community, and vice versa.18

At root, the Iliad is a story about whether Achilles' wrath is justified, as the opening line of the proem shows: "Sing muse, the wrath of Achilles, Peleus' son…." Here, Homer is alluding to the affront suffered by Achilles when Agamemnon, king of the "long-haired Achaeans" (i.e. the Mycenaean Greeks) and leader of the Greek expedition to Troy, took Briseis—the daughter of King Brises—as a war prize, despite having already been awarded to Achilles.19 Agamemnon's actions produced a powerful emotional response in Achilles that drives the Iliad forward. As Walsh explains, in Homeric terms Achilles' response is both mênis (i.e. a character associated with the "prodigious and awesome" wrath of gods, heroes, and the dead20) and khólos (i.e. anger, broadly applied).21 His honor damaged, Achilles was "filled with menos,"22 and thus removed not only himself from the battlefield, but also ordered his men to follow suit. In the story, the Mycenaeans under Agamemnon then suffered repeated defeats at the hands of the Trojans (being aided in their cause by Zeus), prompting the Greeks to entreat Achilles to return to the fray. Yet Achilles steadfastly refused, choosing instead to confine himself to his tent. Only when his devoted friend Patroclus was slain by the Trojan Hector did Achilles return, but not because he owed anything to the Greeks. Rather, Achilles returned because he owed something to Patroclus.

Writ large across this literary struggle is an allusion to a political struggle then unfolding in the Archaic Greek world: the forging of nascent political communities. Indeed, as McCoy has observed, despite being "strictly 'pre-political,' . . . the Iliad actively concerns itself with questions as to how the community is formed . . . ."23 In the conflict between Agamemnon and Achilles, and the violence that ensued, questions were being asked and, to an extent, answered: What did Agamemnon owe Achilles? Should Achilles recognize the authority of Agamemnon? What did Achilles owe Patroclus? What were Achilles' obligations to the Achaeans and vice versa? At the level of the political community then developing in the ancient Greek world, much the same questions were being asked: Who, ultimately, could participate and determine the political fate of a community? Who decides? What demands could be made of individuals? What demands could individuals make of the community at large? What, finally, is the nature of authority? In the world of the polis, the answer to these questions was ultimately provided not by the great and powerful eupatridae, as had been the case in the Athenian Greek past, but rather by the ordinary people, the citizens. It would be they who did the debating and the deciding, a group of people who increasingly came to see that they had no betters and were equals and whose responsibility it was to defend their community from outsiders.

In discussing these elements with students, the Iliad is revealed as more than an expression of Greek literary achievement. It is also an historical document that, when read with a critical if appraising eye, provides a tangible link between ancient Greek conceptions of politics and communities and contemporary debates surrounding questions of individual and communal obligations, themselves a basis of republican democracy. The Homeric epic was likewise an historical document for the Greeks, for it told them about their mythical, glorious past. But it was also a great deal more to them: the Iliad was central to paideia (trans. var. "education," "culture," "training") and, as such, the basis of the ancient Greek educational system.24 Unlike students today, young Greek men read the Iliad not just to be entertained or as part of an assignment, but also to understand what it meant to be Greek, how Greek males were meant to behave and interact, what their obligations were, and provided a framework for Greek mores and values. In other words, it inculcated in them features of to Hellēnikon, or Greekness.25

|

|||

| Figure 4: Terracotta Funerary Plaque. Prothesis (laying out of the dead); below, chariot race. Archaic Greek terracotta black figure plaque.26 | |||

As the Greeks grappled with notions of communal identity, obligation, and political forms, and as the Homeric epics were being transmitted, another ancient civilization was experiencing similar revolutions thousands of miles to the east: Vedic India. A civilization that students of ancient history tend to be less familiar with than ancient Greece, Vedic India (ca. 1500–500 BCE) is another of the great Axial Age societies. Like the Greek Archaic Period, the Vedic Period of ancient India produced epic poetry that provides historians and students with insight into contemporary civilizational developments. Unlike the Homeric epic, however, Vedic poetry was not concerned primarily with something like paideia. Rather, the Vedas (after which the age is named) are focused on issues of spirituality and theology: They are the foundational texts of Hinduism.

Focus on India

Ancient Indian culture was shaped by the emergence of Hinduism, a religious belief system that most scholars argue originated in part with the stories brought to northern India by nomadic migrants who called themselves Aryans ("noble ones") around 1900 BCE, perhaps earlier. The slow commingling of the Sanskrit-speaking Aryans with the indigenous peoples of the Indus Valley produced an Indo-Aryan cultural fusion. Gradually, this culture migrated eastward toward the Ganges River Valley, and over the centuries created the rich oral tradition of the Vedas.27 The Sanskrit Vedas and the epics eventually came to form much of the traditional bedrock of what today is called Hinduism. This oral literature includes the Rig Veda—the earliest, which dates from the Indus Valley's Old Vedic Period, ca. 12th century BCE28—and the later Upanishads, the Puranas, the Rāmāyana, and the Mahābhārata.29 Primarily concerned with religion, this body of work evolved over centuries of oral transmission.

Of all the ancient Indian epics and poems that are part of Vedic tradition, that which is most like the Iliad is the Mahābhārata. As with the composition and eventual construction of the Iliad, the Mahābhārata is part of a long and evolving tradition of storytelling among an illiterate civilization, coming together in written form sometime between the 4th century BCE and the 4th century CE.30 Like the Iliad, the society described in the Indian epics is one that is male-dominated and organized into small kingdoms in which a warlord and his retinue fights against other warlords for resources and for status.31 Indeed, the Mahābhārata depicts the struggle between two related groups, the Pandavas and the Kauravas, cousins locked in a war over the throne of Hastinapura. Early on, the two groups are situated into archetypes. One was the virtuous Pandavas, the eldest of which, Pandu, was awarded the throne because his brother, Dhritirashtra, head of the Kaurava, was congenitally blind, which by honored tradition, disqualified Dhritirashtra from becoming a ruler. Dhritirashtra's sons felt the elevation of the Pandavas thwarted their family honor. They were so determined to prevent a Pandava succession following the death of Pandu, that through unrighteous and devious means they attempted to discredit and even kill Pandu's five sons while they played and trained together so as to clear their own path to the throne.32 Here we are presented with circumstances that resonate with the Iliad: it was grievance and impugned honor that fueled the conflict between Achilles and Agamemnon.

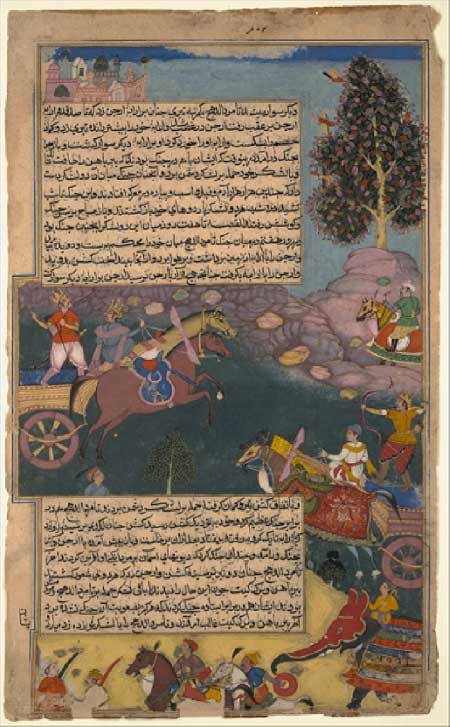

The Kauravan/Pandavan familial discord climaxes in a stereotypically all-male activity: a cataclysmic, 18-day battle known as the Kurukshetra War (alt. the Mahābhārata War). As the centerpiece of the Mahābhārata, the significance of the war parallels that of the Trojan War, itself the context of the Iliad. In both poems, the details of war are similar, from the types of weapons used (swords, spears, bows, shields, and chariots; although the Kurukshetra War also features war elephants) and the sites of battle (fortified towns or strongholds; puras in the Mahābhārata, the city of Troy/Ilion in the Iliad), to the role the gods play in the conflicts.33 In the Iliad, for example, it is Zeus to whom the outraged Achilles prays to bring ruin to Agamemnon's forces, while Athena, disguised as a Trojan, convinces a soldier to fire on Menelaus in order to rekindle the fighting outside Troy. The gods of the Mahābhārata are no less interventionist, as the example of the dialogue between Prince Arjuna and the Lord Krishna demonstrates. Hesitant to go to war against his cousins because he knows that he will have to kill them and many of their own teachers and friends allied to them, Arjuna confesses to Krishna his reluctance to act. Krishna, no mere mortal, but an avatar of Brahman, the divine universal spirit, disguised as Arjuna princely chariot driver, schools Arjuna in his obligations to act as a warrior he must fulfill his dharma (i.e. the selfless execution of their earthly duties) as a ruler, which meant upholding righteous authority in each of their spheres. Everyone in this ancient society had a prescribed duty and role they had to fulfill because, as Krishna explains, failure to do so risked disrupting the delicate balance of the universe, which was constantly threatened by the demons of ignorance, falsehood, and impurity and individual sins.34 The Kauravas were selfish men seeking power denied them by honored tradition. To further allay Arjuna's concerns, Krishna reminded him that the death of the corporeal "self" did not destroy the ātman (eternal soul) within, which was part of the divine aspect of the universe (Brahman) and could not be killed.

|

|||

| Figure 5: "Krishna teaching Arjuna." House decoration in Bishnupur, West Bengal, India. Creator: Arnab Dutta. 35 | |||

Krishna's advice to Arjuna reflects a direct parallel with contemporary events of the Vedic period, which witnessed the gradual development and ossification of what was to become an evolving hierarchical social structure known to West as the Indian caste system. While scholars argue over whether the nucleus of this system was imported with the Aryans, it was not until the late Vedic Age that it began to crystallize.36 Such a system had a twofold purpose: first, it legitimated the varnas, the quartet of classes (Brahmin, priest; Kshatriya, administrator/warrior; Vaishya, merchant; and Shudra (servile class) on which the smooth operation of the universe as well as human society depended. Second, it provided a theological basis for the concept of earthly rebirth after death (saṃsāra) that awaited the ātman or soul which failed in the performance of the righteous duty assigned it. Nothing like this appears in either the Odyssey or the Iliad, which is foremost a manual on Greekness, marking an important distinction between the texts and the civilizations which produced them, and a rich topic to mine during class-based discussion. Indeed, it presents a unique opportunity for instructors to contrast decentralized ancient Greek religion against the increasingly centralized and ordered belief system of near-contemporary Vedic Age India. Class-based exercises for doing so within an active learning framework can be found in the appendices of this essay, under the headings "Defining Axial Age Civilizations" (Appendix I) and "A Geography of Axial Age Civilizations" (Appendix II).

Despite the emphatic difference between them, the epics nevertheless share many other similarities. While "ordinary women" in both traditions are usually depicted as commanding little influence or respect, upper-class women tend to subvert the popular perception of misogynistic male dominance in classical literature by exercising a demonstrable degree of influence and agency. As Mary R. Lefkowitz argues, despite severe legal circumscriptions, certain women in the Homeric epics manage to "exert significant moral force" by virtue of their frequent commentary on the action.37 A perhaps unexpected example of this is Briseis, whose status as a war-captive would seem to altogether preclude agency. However, she is not voiceless in the Iliad and although she speaks very few words, they are significant.38 Upon the death of Patroclus, Homer puts a lament in the mouth of Briseis that vividly portrays the effects of war on women:39

So evil begets evil for me forever. The husband to whom my father and mistress mother gave me I saw torn by the sharp bronze before the city, and my three brothers, whom one mother bore together with me, beloved ones, all of whom met their day of destruction. Nor did you allow me, when swift Achilles killed my husband and sacked the city of god-like Mynes, to weep, but you claimed that you would make me the wedded wife of god-like Achilles and that you would bring me in the ships to Phthia, and give me a wedding feast among the Myrmidons Therefore, I weep for you now that you are dead ceaselessly, you who were kind always.40

Unhappy with being forced to leave Achilles (despite the fact that he killed her husband) and mournful over the loss of Patroclus, Briseis is shown here to be more than a mute object passively accepting the fate that befell her as a "warrior's booty";41 in the space of a few lines, the poet has rendered Briseis both a complex figure of tragedy and an exemplar of faithfulness, the latter a characteristic shared with other female characters in the Homeric epics, notably Penelope, the companion of Odysseus. Yet even Penelope, cast as the archetypal Greek "good wife," is multidimensional; while she is faithful and submissive to Odysseus, she is also cunning and guileful.42 As the contest for her hand in (re)marriage unfolds, Penelope manipulates would-be suitors to delay an otherwise inevitable outcome in light of Odysseus' long absence. For example, she promises to remarry upon the completion of the death shroud she is weaving for Laertes, Odysseus' elderly father, only to frustrate the designs of others by nightly undoing her work.43

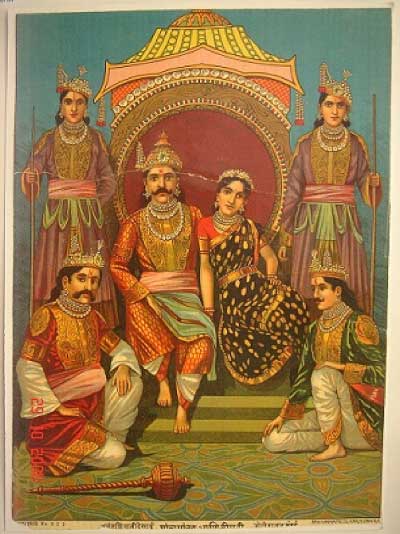

Undergraduates exposed to Western canonical literary tradition may already be aware of such nuance in the Homeric epics; they are often surprised, however, to learn of such complex gender dynamics in the Mahābhārata, which they imagine as having been produced by an Axial Age society more staid and conservative than the Greeks. To be sure, female characters in each epic do share similar plots and characteristics. The Indian princess Draupadi, for instance, is both a prize to be had and the cause of the conflict at the heart of the narrative, elements that echo the character and arc of Helen in the Iliad. As Alleyn Diesel explains, Draupadi is "regarded by many men as a prize, a valuable object to be competed for and squabbled over, and she becomes the central reason for internecine conflict, which brings disorder (adharma) and devastation to society."44 Yet another similarity is that, as with Penelope in the Odyssey, the winning of Draupadi's hand in marriage hinges on a complex archery contest between suitors, during which the ultimate victors (Odysseus in the case of Penelope, Arjuna in the case of Draupadi) must disguise themselves. Such parallels are part of a familiar package of tropes and formulae present in many classical texts, but they are useful to students in that they help shed light on the mores and values which prevailed in the male-dominated, patriarchal societies which produced them.

|

|||

| Figure 6: "Draupadi and the Five Pandava Brothers." Painting by Raja Ravi Varma (1848–1906).45 | |||

Despite these parallels, there are present in the Mahābhārata notable divergences in gender stereotypes. While Draupadi is an archetypal "good wife" in a vein broadly analogous to that of Penelope, it is a role that is entirely a product of Ancient Indian culture and tradition. Certainly, Draupadi is a devoted and faithful wife, but within a dynamic of fraternal matrimonial polyandry—that is, she is the wife of the five Pandava brothers.46 Yet she is anything but a passive instrument of her husbands' designs; although she accepts her "legitimized pluralization" as a means by which her husbands could demonstrate their glory, she does not suffer in silence when placed in situations of conflict and tension involving them.47 For example, following her grievous humiliation at a dice match, the outcome of which resulted in the banishment of the Pandavas, Draupadi confronted her husband and rightful king of Hastinapura, Yudhishthira.48 She was appalled by his resigned acceptance of their ruination at the hands of the Kauravas who rigged the dice game. She was also so angry to the mean state to which they had sunk, she questioned his behavior. Yudhishthira knew the game was rigged but stayed in the game in the hope that his losses would eventually spark remorse in his childhood friends and thus save their souls. It did not, and Draupadi was furious he did not stop until he had gambled away everything he had, including his four brothers and Draupadi herself!

To see you . . . now in this state, mud spattered, clad in deerskin, sleeping on hard ground—oh it wrings my heart. To see Bhima [Yudhishthira's brother, and husband in common] who achieves single-handed every victory, now in this distressing state, does it not stir your anger? Arjuna [another brother -husband and greatest warrior of all . . . bound hand and foot, does it not make you indignant? Why does not your anger blaze up and consume your enemies? And me, the daughter of Drupada and sister of Dhrishtadyumna, disgraced and forced to live like this! How is it you are so mild? There is no kshatriya who is incapable of anger, so they say, but your attitude does not prove it.49

Here, the vengeful Draupadi has challenged a behavioral norm and subverted tradition, an unimaginable step for a woman of her time and setting.50

Such contrasts between the Greek and Indian epic tradition provide historians of the ancient world with an entrée into coursework aimed at developing among students a complex understanding of gender roles in ancient societies. Here, the significance is not only that they are alike, but that they are markedly dissimilar. For students in World History courses, it is important to draw out this dynamic and encourage analysis of it. For while many may be aware of today's evolving societal norms, equally as many students may not be. It is beneficial to explore the obvious suggestion that there is a natural tendency of certain ancient societies to structure themselves within a male-dominated, patriarchal framework—with all its attendant implications for the development of those societies—the myriad ways in which ancient literature challenges this notion, and how this compares to circumstances in the modern world.

|

|||

| Figure 7: "Arjuna Battles Raja Tamradhvaja." Folio from the Razmnama, which means "Book of War," a Persian translation of the Hindu epic poem Mahābhārata. commissioned by the Mughal Emperor Akbar in India. Ca. 1616–17.51 | |||

It is worth elaborating a further point of comparison to return us to the overarching worldview of the ancient contemporaries who produced these epics. The trio of works considered in this study all share a striking nostalgia (Gr. Nostos + Algos) for a bygone "Heroic Age," a tendency which scholars have identified as a leitmotif of epic tradition. Indeed, for Gregory Nagy, the Odyssey represents something of a pinnacle of this reflective quality: it is the "final and definitive statement about the theme of heroic homecoming: in the process of retelling the return of the epic hero Odysseus, the narrative of the Odyssey achieves a sense of closure in the retelling of all feats stemming from the heroic age."52 William Allan, meanwhile, recognizes a sense of return mixed with yearning pride in the Iliad as, for example, when Homer compares the physical superiority of the warrior heroes with the men of his own day: "A man could not easily lift that rock with both hands, even a very strong man, such as mortals now are."53 Neatly framed by Michael Grant, the Greeks of Homer's day saw "something splendid and superhuman about what they supposed to be their lost past."54 In other words, things were not only different in this earlier Heroic Age, the mythical setting of the Homeric epics; they were better, too.

The work of Homer reflects a trend in Archaic Greek thinking that had gained currency: the Hesiodic myth of human degeneration. A contemporary of Homer, Hesiod expressed in his Works and Days a bleak vision of mankind as regressing in a sequence of deteriorations, a "progressive falling away from the Golden Race ('guardians of justice' who lived in Kronos' age, when he was monarch of heaven), through an Age of Silver . . . a Bronze Age with its semi-divine Heroes, to the violent Age of Iron"—that is, the Age of Man. Homer's narrative was informed by this theme, which is echoed in the Mahābhārata. Indeed, not only does the Ancient Indian epic recall Greek nostalgia for heroic virtue, as heightened by the exploits of the five sons of Pandu, but, as Barry Sandywell has observed, a similar chronology of decline and "fallenness" pervades throughout. Beginning with a "Golden Age," the krta yuga, where there was but one religion, no disease or sorrow or fear, where "all mankind could obtain supreme blessedness," the human race gradually degenerates over the course of four yugas (the manvantara), each producing an epoch less glorious and less virtuous than the last, until eventually reaching another "Age of Iron":55 the kali-yuga or, as Gavin Flood notes, the "present age of darkness."56

Enormously destructive of both men and materiel, the wars at the center of these epics were nevertheless the vehicle for the pronounced glorification of their heroic protagonists, as we have seen. Yet in many respects, the Iliad, the Odyssey, and the Mahābhārata are also unexpected meditations on the costs of war, an aspect of these works students of Ancient World History would do well to remember. Numerous passages in both the Mahābhārata and the Iliad prompt deep reflection on the horrors and tragedies of war, as already suggested by the above passage concerning Briseis. Consider, for example, Achilles' destruction of the defeated Hector. Lying helpless before the Greek, Hector begs not for his life, but that his body not be dishonored in death: "I beg you, Achilles, by your own soul and by your parents, do not allow the dogs to mutilate my body." But Hector's entreaty falls on deaf ears, as the vengeful Achilles rejects his plea: "Hector, do not try to reason with me, do not entreat me, you vile dog . . . I wish only that my rage would drive me to hack away your flesh and eat it raw for what you have done to me. There will be no one to keep the dogs from feasting on your head, the dogs and the birds will have your corpse to dine upon." Achilles vents his rage abominably. After slaying a dozen Trojan captives, he mutilates and mistreats Hector's corpse and refuses to allow it to be buried, a great affront to any Greek hero.57

The excessiveness of Achilles' behavior is matched (if not exceeded) by Bhima, one of the greatest warriors of the Pandava clan. Following the game of dice at which Yudhishthira wagered Draupadi and lost, she was ritually humiliated by the Kaurava prince, Duhsasana. This deeply shameful event prompted Bhima to avenge the insult, which he later does in a horrific act of violence:

Drawing then his whetted sword of keen edge, and trembling with rage, he placed his foot upon the throat of Duhsasana, and ripping open the breast of his enemy stretched on the ground, Bhima drank his warm life-blood. Then gazing at the corpse with wrathful eyes, he said "I regard the taste of this blood of my enemy to be superior to that of my mother's milk, or honey, or clarified butter, or good wine, or all other kinds of drinks there are on earth that are [as] sweet as ambrosia or nectar." . . . Those that saw Bhima, while filled with joy at having drunk the blood of his foe, uttering those words and stalking the field of battle, all fled away, overwhelmed with fear, and [they] said to one another, "This Bhima must be a rakshahsa! [a demon]"58

Both Bhima and Achilles lost control and transgressed against the normal rules of behavior. In dehumanizing their victims, they violated taboos, including cannibalism, and abrogated the social mores and values which bound and underpinned their societies. To be sure, the epics valorize the deeds of the heroes, but they also reveal some of the dire costs of war: the brutalization of life, the replacement of civilization with barbarousness, and, in the void created by the absence of restraint, a potentially endless cycle of violence as the affronted and aggrieved seek revenge.

Conclusion

Instructors and students of Ancient World History should be conscious of the fact that the Axial Age is not an uncontroversial periodization. Framed initially by Karl Jaspers in The Origin and Goal of History, and popularized recently by such historians as Karen Armstrong,59 critics such as Antony Black argue that Jaspers vested the "coincidence" of civilizational phenomena, including the work of Plato, Confucius, and the Indian Upanishads with too much significance, and that the "language and approach" employed by Jaspers "are seriously liable to misrepresent what actually happened both then and later."60 While such criticism is justifiable to a point, students should be aware that the same can and has been said of most culturally-dependent periodizations employed by historians, and that its usefulness and applicability is conditional on the types of questions being interrogated by the historian. As historians such as Norman Cantor, William Caferro, and Gillian Clark have demonstrated for the medieval period, the Renaissance, and late antiquity, respectively, the periodization of human history through temporal bookends and cultural phenomena is fraught and open to varying interpretations. For the purposes of this study, the Axial Age is employed to refer to this epoch because the period beginning around the 9th century BCE was an age of profound cultural change across human civilizations, from philosophical thought among the Greeks (beginning with the rationalists of Ionia, ca. 6th century BCE) to the elucidation of religious philosophy in India in the Upanishads (the earliest of which, Patrick Olivelle explains, date from around the 7th or 6th centuries BCE)61 and the crystallization of Zoroastrian thought in the "Young Avestan" texts of the Persian Achaemenids (ca. 6th-4th centuries BCE).62 Thus, this work, like that of S. N. Eisenstadt, Baruch Halpern and Kenneth Sacks, and Hans Joas and Robert N. Bellah, has adopted the position that the Axial Age was a period when civilizations pivoted away from many old traditions toward something new and different.63

The historicity of the events at the center of the Iliad, the Odyssey, and the Mahābhārata continues to be the source of scholarly debate. While there is no consensus, it is important to engage with this debate in the classroom for several reasons. First, it encourages instructors to think critically about our sources of knowledge and how another discipline (in this case, the literary arts) can provide otherwise irretrievable insight into historical events. As Allan H. Pasco has argued, "No well-trained historian or critic would today deny that creative works form a significant, well-integrated part of that tapestry created by a period's economic, social, and political beliefs and values. It is the way individuals think and feel about a society that characterizes them and their times, marking their differences from people that preceded and followed them. This is true for all periods . . . ."64 Second, it allows students to develop an appreciation for the potential of interdisciplinarity to enrich the histories they are studying and, in many cases, writing. To this end, a "Virtual Archaeological Dig" exercise has been included in the appendices of this essay. The exercise provides students the opportunity to "digitally excavate" the historicity of the past by looking at diagnostic evidence related to both ancient Greek and ancient Indian civilizations (Appendix III).

Indeed, there is both archaeological and historical evidence to suggest that the events described in the epics have a basis in historical fact. Heinrich Schliemann in the 19th century did much to confirm the existence and location of Homer's Troy, which he confidently identified as being buried beneath the city of Hissarlik in modern-day Turkey.65 Aiding Schliemann in his search for Troy was the Iliad, which the archaeologist believed held clues to the location of the fabled city. Indeed, Schliemann used the Homeric epics to locate and excavate many of the famous Mycenaean sites mentioned in the Iliad and the Odyssey, including such Peloponnesian sites as Pylos, Corinth, and Mycenae. Intense archaeological scrutiny has borne out the fact that these sites existed around the time of the Trojan War (ca. 12th century BCE or earlier) and seem to have had some trade-based relationship with Troy. Despite this, the Iliad must be considered critically by teachers and students of Ancient World History, for there are also historical inaccuracies: we find soldiers wielding Iron-Age weapons in a conflict that transpired during the Bronze Age. Also, Homer's story includes chariots, which the author knew existed in the distant Greek past, although it is clear he did not know exactly what purpose they served in battle.66

Evidence of the Kurukshetra War is more elusive. There is doubt as to when the event happened, if at all. Some scholars argue that it took place around the 4th millennium BCE (a date arrived at in large part through the use of astronomical data),67 while others argue the war happened around the 9th century BCE.68 While there is some evidence suggesting the truth of some of the events described in the Indian epic, there are also archaeological voids. For example, there is no inscriptional evidence that proves the historicity of the Mahābhārata, although some ancient literary texts, including the Artharva Veda and Kautilya's manual for political administration, the Arthashastra, do support the historical reality of the Kurukshetra War.69

For all this, the Iliad, the Odyssey, and the Mahābhārata offer insight into both the Axial Age and the civilizations that created them. Separated by thousands of miles and having no direct or indirect influence on each other, the ancient Greeks and ancient Indians produced surprisingly similar literature that indicated they were going through analogous stages of development. All are cornerstones of these civilizations; all were originally part of oral traditions that look back to a "golden age"; all are concerned predominately with military matters and the acts of gods and heroes; and all were not finally written down until centuries after the events they describe.70 Taken together, these works reveal male-dominated societies, concerned with honor and prestige; evolving religious traditions, some with lasting implications for the modern world; and civilizations whose mores and values came cloaked in the guise of war. When the Axial Age waned, both societies had new understandings of what constituted the political community, obligations and duties, and identity.

Appendix I

Defining Axial Age Civilizations

Students can use this rubric to contrast the commonalities and divergences characteristic of each of several Axial Age societies. Once complete, instructors should have students get into groups of 3 or 4 (depending on class size) to discuss and compare their findings.

Prompt for Student Discussion: "What characteristics define these civilizations as 'Axial Age'?"

Achaemenid Persia |

Ancient China |

Ancient Israel |

Ancient India |

Ancient Greece |

|

Name of Religion or Philosophy |

|

||||

Core Beliefs or Tenets |

|

||||

Central/Key Text(s) |

|

||||

Central/Key Figure(s) |

|||||

Year Founded |

|||||

Student Notes |

|

||||

Suggested Readings |

E. Pollard, C. Rosenberg et al, Worlds Together, Worlds Apart with Sources: Concise Second Edition, Vol. 1 (2019): Chapter 4; R. Strayer and E. Nelson, Ways of the World: A Brief Global History with Sources: 3rd Edition (2015): Chapter 4 |

||||

Instructor Notes: When considering how these civilizations meet the criteria of Axial Age civilizations, students should focus on social, religious, and political changes during the first millennium BCE. In the case of Persia, for example, a defining trait is the crystallization of Zoroastrianism under the Achaemenids; in China, the developments of Confucian philosophy, and its rivals (including Daoism) during and after the Warring States Period; in Ancient Israel, the evolution of Judaism and its attendant laws and moral code (e.g. Deuteronomy).

Appendix II

A Geography of the Axial Age

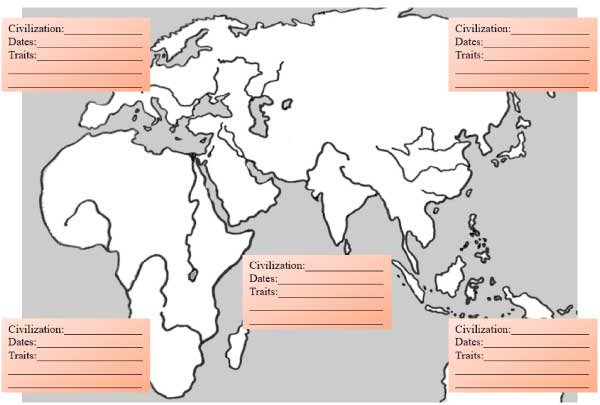

|

|||

| Appendix Figure 1: Map of ancient Eurasia. | |||

Instructions

Students can use this map to develop a chronology and spatiality of the Axial Age and then discuss the implications of these things. Students should:

- Place the Axial Age civilizations on the map in their correct location by drawing lines connecting each of the textboxes to a specific place on the map.

- Students should complete each textbox by listing a rough chronology of the period for each of the civilizations (these chronologies will differ) and list some of the traits or changes in thought, politics, religion, and social structure each civilization experienced.

After students have completed their maps, the instructor can extend the exercise by contextualizing Axial Age developments for each civilization through in-class discussion. The following prompts are suggested to encourage discussion and critical thinking.

- Describe each civilizations' historical context before and during the Axial Age.

- Which circumstance or event do you feel was most important to advancing these developments?

- What are some of the implications of these developments for human societies?

Suggested Readings: E. Pollard, C. Rosenberg et al, Worlds Together, Worlds Apart with Sources: Concise Second Edition, Vol. 1 (2019): Chapter 4; R. Strayer and E. Nelson, Ways of the World: A Brief Global History with Sources: 3rd Edition (2015): Chapter 4 |

Appendix III

Virtual Archaeological Dig: "Beyond the Trenches"

Archaeology is a critical component in the study of ancient civilizations. Diagnostic evidence retrieved from archaeological digs has been used confirm or reject ancient historical accounts. One of the most famous examples of this is the work of Heinrich Schliemann in the 19th century. An amateur archaeologist interested in the story of the Trojan War as related in Homer's Iliad, Schliemann engaged in digs around the Aegean Sea and Mediterranean Sea in an effort not only to find the city of Troy (reckoned to be somewhere in the northwestern quadrant of modern-day Turkey along the Dardanelles), but also to connect it with the history of the earliest Greeks, the Achaeans, the people who attacked Troy. Schliemann's work identifying the archaeological remains of these civilizations helped to confirm the historicity of certain aspects of Homer's ancient epic, including place names, types of weaponry, and sociocultural elements.

In the classroom, the use of archaeology in a lesson or course on Ancient World History has many benefits. First, it introduces interdisciplinarity between two complementary fields of study. This encourages students to adapt analytical and critical thinking skills that are already key components of historical inquiry to the realm of physical evidence. Second, it provides students a scientific framework to use in their own research, including the formulation of hypotheses, data analysis, conclusion formulation, and detailed record keeping. In addition to the development of higher order thinking among students, a virtual dig has the benefit of making the physical remains of the ancient world available to universities and colleges that otherwise lack ready access to diagnostic evidence to complement a course in Ancient World History.

"Beyond the Trenches" is designed to transform the classroom space into a digital archaeological dig. Using the images below, instructors can have students analyze diagnostic evidence and speculate as to their meaning and historical accuracy in relation to the Axial Age civilizations discussed in the essay above. To assist students in their analyses, a "Digital Field Log" template has been provided. Students complete one of these for each piece of evidence and bring them together as they speculate in groups on how the remains reflect aspects of Ancient Greek and Ancient Indian civilization.

Instructions

Have students look at these images and complete one "Digital Field Log" for each. Have them draw the piece, speculate what material(s) they are made of, and what they depict. Upon completion, put students in groups of 3–4 (depending on class size) to discuss their findings and speculations. This can serve as the basis of an in-class discussion about the relevance of the diagnostic evidence to a) the stories as told in the Iliad and Mahābhārata and b) what the archaeology tells the students about the history of the societies that produced it. The instructor should then guide the students to the New York Metropolitan Museum of Arts' digital repository (https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search#!?searchField=All&showOnly=openAccess&sortBy=Relevance&offset=0&pageSize=0), have them look at the descriptions for each, and then resume group discussion considering the new evidence.

Digital Field Log

Digital Excavation Team Member: _____________________________________

Artifact

|

Artifact Number |

Artifact Sketch (include details)

|

|

Notes

|

|

Appendix Figure 2: Field Log Template.

|

|||

| Appendix Figure 3: "Arjuna Battles Raja Tamradhvaja." Folio from the Razmnama, which means "Book of War," a Persian translation of the Hindu epic poem Mahābhārata. commissioned by the Mughal Emperor Akbar in India. Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper. Ca. 1616–17.71 | |||

|

|||

| Appendix Figure 4: "Council of Heroes." Page from a dispersed Mahābhārata (Great Descendants of Mahābhārata). Maharashtra, Paithan (India). Ink and opaque watercolor on paper. (ca. 1800)72 | |||

|

|||

| Appendix Figure 5: Kris with Sheath. Malaysian. Iron, gold, wood. (18th–19th century)73 | |||

|

|||

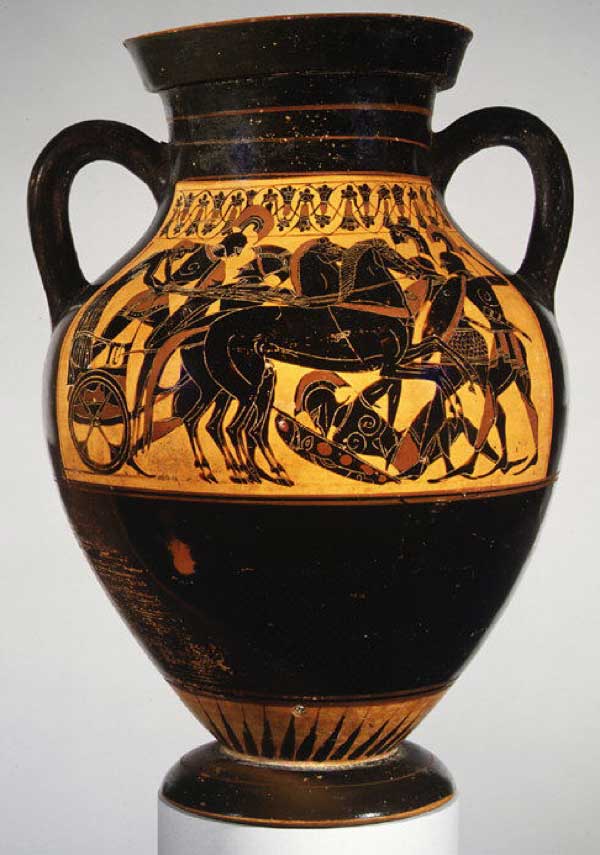

| Appendix Figure 6: Terracotta amphora (jar). Attributed to the Princeton Painter (Greek, Attic). Terracotta; black-figure. (ca. 500–490 BCE)74 | |||

|

|||

| Appendix Figure 7: Marble relief fragment with scenes from the Trojan War. Roman. Marble, Palombino. (1st half of 1st century CE)75 | |||

|

|||

| Appendix Figure 8: Bronze chariot inlaid with ivory. Etruscan. Bronze, ivory. (2nd quarter of the 6th century BCE)76 | |||

Appendix IV

Student Exercises: Homework & In-class Discussion

Have students complete a "Comparative Matrix" where they ask and answer the same questions about two or more Axial Age texts. See below:

Instructions: Use this matrix to help quickly and easily create a comparison between the Iliad and the Mahābhārata. Complete each cell with specific details you find in the book that answers the question listed in the far-left column. Include the page and author citation details to make the process of writing your final essay simpler. Remember that all work must be properly cited.

Question |

The Iliad |

Page & Author Citation |

The Mahābhārata |

Page & Author Citation |

Discuss the context of these works' creation. Were these works written before, during, or after the events they describe? Why are these important questions to ask? |

||||

Discuss the events that the authors focus on in these works. How are they similar and how are they different? |

||||

Reflect on the behaviors of Bhima and Achilles during battle and compare and contrast them. |

||||

What role(s) do gods or deities play in these epics? How are the Greek gods similar to the Indian gods in their behaviors and vice versa? |

||||

How does the works' authorship parallel each other? Critically assess why this is significant, given that these societies developed independently of each other in vastly different geographic circumstances. |

Joseph M. Snyder is Assistant Professor of History at Southeast Missouri State University, where he teaches graduate courses in World Civilizations and British Imperial History, as well as undergraduate courses in historiography and British, African, Greek, and Roman histories. Dr. Snyder also sits on the Editorial Board of World History Bulletin, a publication of the World History Association. He can be reached via email at jmsnyder@semo.edu.

1 The source for this

image is The New York Metropolitan Museum of Art, used in accordance with the

provisions for free use established by the donor. It may be found at: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/361905?searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&showOnly=openAccess&ft=iliad

&offset=20&rpp=20&pos=35.

2 The

source for this image is The New York Metropolitan Museum of Art, used in

accordance with the provisions for free use established by the donor. It may be

found at: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/37933?searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&showOnly=openAccess&ft=mahabharata

&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=3 Accessed

December 27, 2019.

3 Broadly-speaking, the historical parallelisms and themes explored in this study are commonalities shared by many "classical" war epics, including more recent epics such as Heike Monogatari, produced by medieval Japan's somewhat insular war culture. This phenomenon suggests that an equally rich alternative strategy to approaching and understanding the Axial Age may perhaps be one based on the comparative study of historical-cultural features, rather than chronological periodization.

4 Karl Jaspers, The Origin and Goal of History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1953), 1.

5 S. N. Eisenstadt, "The Axial Age Breakthroughs," in S. N. Eisenstadt, ed., The Origins and Diversity of Axial Age Civilizations (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1986), 15.

6 John Brockington, The Sanskrit Epics (Leiden: Brill, 1998), 26.

7 Howard James Cannatella, "Plato and Aristotle's Educational Lessons from the Iliad," in Paideusis 15 no. 2 (2006), 1–2.

8 The so-called "Pisistratean Recension." See Øivind Andersen, "Pisistratean Recension," in M. Finkelberg, ed., The Homer Encyclopedia (Hoboken: Wiley, 2011), https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/wileyhom/pisistratean_recension/0?institutionId=1804 Accessed December 20, 2019; Gregory Nagy, "Homeric Scholia," in Ian Morris and Barry Powell, eds., A New Companion to Homer (Brill: Leiden, 1997), 101–122; J. B. Bury, The History of Greece (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 198.

9 Charles Freeman, Egypt, Greece, and Rome: Civilizations of the Ancient Mediterranean (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 128.

10 As quoted in Casey Dué, "Learning Lessons from the Trojan War: Briseis and the Theme of Force," in K. Myrsiades, ed., Approaches to Homer's Iliad and Odyssey (New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2010), 121.

11 Werner Jaeger, Paideia: The Ideals of Greek Culture, Vol. I (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1973), 10–35; A. W. H. Adkins, Merit and Responsibility: A Study in Greek Values (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1960), 30–85.

12 Margarlit Finkelberg, "Timē and Aretē in Homer," The Classical Quarterly 48 no. 1 (1998), 14–16.

13 The

source for this image is The New York Metropolitan Museum of Art, used in

accordance with the provisions for free use established by the donor. It may be

found at: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/416625?searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&showOnly=openAccess&ft=achilles

&offset=20&rpp=20&pos=31. Accessed December

27, 2019.

14 Jonathan L. Ready, Character, Narrator, and Simile in the Iliad (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 268–269.

15 Erwin Cook, "Introduction," in E. McCrorie, trans., The Iliad (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), xxvi.

16 Christos C. Tsagalis, "Rhapsodic Recitals in the Archaic and Classical Periods," in Jonathan Ready and Christos C. Tsagalis, eds., Homer in Performance: Rhapsodes, Narrators, and Characters (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2018), 37–52.

17 Olga Levaniouk, "Comparative Perspectives on Homeric Singers," in Jonathan Ready and Christos C. Tsagalis, eds., Homer in Performance: Rhapsodes, Narrators, and Characters (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2018), 190–192.

18 John Gould, Myth, Ritual, Memory, and Exchange: Essays in Greek Literature and Culture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 335–358.

19 Homer, The Iliad, trans. B. Powell (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 204.

20 D. L. Cairns, "Ethics, Ethology, Terminology: Iliadic Anger and the Cross-Cultural Study of Emotion" in S. Braund and G. Most, eds., Ancient Anger: Perspectives from Homer to Galen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 33. Scholars have been opening new perspectives on the Homeric epics by developing more nuanced approaches to such fundamental components of the works as the language used. A particularly fruitful enterprise, this has produced a subset of historical-literary studies that wrestle with the multivalent and context-specific meanings of such concepts as khólos, mênis, kótos, and nemesis, to name a few. The result is an avenue of research that at a minimum de-emphasizes agonistic interpretations of Homeric sensibilities in favor of an exploration of the deep emotionality of the characters, an approach which could resonate with many students. In addition to Cairns and Walsh (below), see Patrick Considine, "The Theme of Divine Wrath in Ancient East Mediterranean Literature," Studi Micenei ed Egeo-Anatolici 8: 85–159; Dean Hammer, "The Iliad as Ethical Thinking: Politics, Pity, and the Operation of Esteem," Arethusa 35 no. 2, 203–235; William V. Harris, Restraining Rage: The Ideology of Anger Control in Classical Antiquity (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001); Mary R. Lefkowitz, "The Heroic Women of Greek Epic," The American Scholar 56 no. 4 (1987), 503–518.

21 Thomas Walsh, Fighting Words and Feuding Words: Anger and the Homeric Poems (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2005), 85.

22 Cairns, "Ethics, Ethology, Terminology," 22.

23 Maria Berzins McCoy, Wounded Heroes: Vulnerability as a Virtue in Ancient Greek Literature and Philosophy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 1–36.

24 Lawrence Kim, Homer Between History and Fiction in Imperial Greek Literature (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 216.

25 Suzanne Said, "The Discourse of Identity in Greek Rhetoric from Isocrates to Aristides," in I. Malkin, ed., Ancient Perceptions of Greek Ethnicity (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001), 289.

26 The

source for this image is The New York Metropolitan Museum of Art, used in

accordance with the provisions for free use established by the donor. It may be

found at: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/254801?searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&showOnly=openAccess&ft=achilles

&offset=20&rpp=20&pos=35 Accessed

December 27, 2019

27 Michael Witzel, "Early Sanskritization: Origins and Development of the Kuru State," Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies 1 no. 4 (1995), 1–4.

28 Witzel, "Early Sanskritization," 1–4.

29 R. U. S. Prasad, The Rig-Vedic and Post-Rig-Vedic Polity (1500–500 BCE) (Wilmington: Vernon Press, 2015), 43.

30 Wendy Doniger, "Transformations of Subjectivity and Memory in Mahabharata and Ramayana," in D. Shulman and G. Stroumsa, ed., Self and Self-Transformation in the History of Religion (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 57.

31 Kaushik Roy, "Hinduism," in G. M. Reichberg, H. Syse, and N. Hartwell, eds., Religion, War, and Ethics: A Sourcebook of Textual Traditions (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 477.

32 Steven Rosen, Krishna's Song: A New Look at the Bhagavad Gita (Westport: Praeger, 2007), 23.

33 Roy, "Hinduism," 476.

34 Gail Hinich Sutherland, The Disguises of the Demon: The Development of the Yakşa in Hinduism and Buddhism (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1991), 56–57.

35 The source for this image is Wikimedia Commons, used in accordance with the provisions for free use established by the donor Arnab Dutta, under license CC BY-SA 3.0 at https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Bhagavad_Gita#/media/File:Bhagavata_Gita_Bishnupur_Arnab_Dutta_2011.JPG.

36 Stuart Cary Welch, India: Art and Culture, 1300–1900 (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1985), 23.

37 Lefkowitz, "The Heroic Women of Greek Epic," 503.

38 Casey Dué, Homeric Variations on a Lament by Briseis (Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc., 2002), 4.

39 Ibid., 2–10.

40 Ibid., 8–10 and Lefkowitz, "The Heroic Women of Greek Epic," 510.

41 Lourens Minnema, Tragic Views of the Human Condition: Cross-Cultural Comparisons Between Views of Human Nature in Greek and Shakespearean Tragedy and the Mahābhārata and Bhagavadgītā (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013), 260.

42 Kathryn Sullivan Kruger, Weaving the Word: The Metaphorics of Weaving and Female Textual Production (Selinsgrove: Susquehanna University Press, 2001), 79–86.

43 Steven Lowenstam, "The Shroud of Laertes and Penelope's Guile," The Classical Journal 95 no. 4 (2000), 3.

44 Alleyn Diesel, "Tales of Women's Suffering: Draupadi and Other Amman Goddesses as Role Models for Women," Journal of Contemporary Religion 7, no. 1 (2002), 9 as quoted in Motswapong Pulane Elizabeth, "Understanding Draupadi as a Paragon of Gender and Resistance," Stellenbosch Theological Journal 3 no. 2 (2017), 6.

45 The

source for this image is Columbia University. It may be found at: http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00routesdata/bce_299

_200/mahabharata/draupadiwife/draupadiwife.html Accessed

December 27, 2019.

46 Elizabeth, "Understanding Draupadi as a Paragon of Gender and Resistance," 7.

47 Ibid., 6.

48 Gavin Flood, An Introduction to Hinduism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 106–107.

49 R. K. Narayan, The Mahabharata: A Shortened Modern Prose Version of the Indian Epic (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978), 76–77.

50 Shreerekha Subramanian, "'Whom Did You Lose First? Yourself or Me?': The Feminine and the Mythic in Indian Cinema," in Sanja Bahun-Radunović and V. G. Julie Rajan, eds., Myth and Violence in the Contemporary Female Text (Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Ltd., 2011), 76.

51 The

source for this image is The New York Metropolitan Museum of Art, used in

accordance with the provisions for free use established by the donor. It may be

found at: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/451314?searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&showOnly=openAccess&ft=

arjuna&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=5 Accessed December 27, 2019.

52 Gregory Nagy, The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2013), 216.

53 William Allan, Classical Literature: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 2014), https://books.google.com/books?

id=-8fRAgAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=a+very+short+introduction+allan+literature&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=

2ahUKEwjQ7_b_mdbmAhXWGs0KHag5AocQ6AEwAHoECAYQAg#v=onepage&q=bygone%20heroic%20age&f=false Accessed

December 27, 2019.

54 Michael Grant, Myths of the Greeks and Romans: A Fascinating Study of the World's Great Myths and Their Impact on the Creative Arts Through the Ages (New York: Meridian, 1995), 45.

55 Barry Sandywell, The Beginnings of European Theorizing: Reflexivity in the Archaic Age—Logological Investigations, Vol. 2 (New York: Routledge, 1996), 201.

56 Flood, An Introduction to Hinduism, 112-113.

57 Robert

L. Oprisko, Homer: A Phenomenology (New York: Routledge, 2012), https://books.google.com/books?id=zBXZ82NumDUC&pg=

PT125&dq=hector+pleads+for+his+life&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwilqY3i4dbmAhVWHc0KHYVlDFsQ6A

EwAHoECAMQAg#v=onepage&q=hector%20pleads%20for%20

his%20life&f=false. Accessed December 27, 2019.

58 D. Singh, "Bhāyanaka (Horror and the Horrific) in Indian Aesthetics," in Kevin Corstophine and Laura R. Kremmel, eds., The Palgrave Handbook to Horror Literature (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018) 28–29.

59 See The Great Transformation: The World in the Time of Buddha, Socrates, Confucius, and Jeremiah (London: Atlantic Books, 2006).

60 Antony Black, "The 'Axial Period': What Was It and What Does It Signify?," Review of Politics 70 (2008), 24–25.

61 Patrick Olivelle, The Early Upanishads (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), xxxvi. Give or take a century.

62 Prods Oktor Skjǣvo, "Avestan Society," in Touraj Darayee, ed., The Oxford Handbook of Iranian History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 58–60. The historiography of the Axial Age is rich and varied, assessing everything from the religious and philosophical dimensions of the period to the appropriation of material culture, propaganda, and even oral traditions across the Mediterranean and Near and Far East—and everything in between. See Baruch Halpern and Kenneth Sacks, Cultural Contact and Appropriation in the Axial-Age Mediterranean World (Brill: Leiden, 2017); S. N. Eisenstadt, The Origins and Diversity of Axial Age Civilizations (Albany: State University of New York, 1986); Robert Bellah and Hans Joas, The Axial Age and Its Consequences (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012).

63 Eisenstadt, "The Axial Age Breakthroughs,"15–18.

64 Allan H. Pasco, "Literature as Historical Archive," New Literary History 35 no. 3 (2004), 389.

65 Susanne Deusterberg, Popular Receptions of Archaeology: Fictional and Factual Texts in 19th and Early 20th Century Britain (Bielfeld: Transcript-Verlag, 2015), 212.

66 G. S. Kirk, Homer and the Oral Tradition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976), 60–65.

67 V. N. Datta, History of Kurukshetra (Vishal: 1985), 24.

68 M. V. Nankarni, The Bhagavad-Gita for the Modern Reader: History, Interpretations, and Philosophy (New York: Routledge, 2017), 226.

69 B. B. Lal, The Historicity of the Mahabharata: Evidence of Literature, Art, and Archaeology (Aryan Books International, 2013), 80–90.

70 Brockington, The Sanskrit Epics, 26.

71 The

source for this image is The New York Metropolitan Museum of Art, used in

accordance with the provisions for free use established by the donor. It may be

found at: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/451314?searchField=All&am2ndp;sortBy=Relevance&showOnly=openAccess&

ft=arjuna&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=5. Accessed December 27, 2019.

72 The

source for this image is The New York Metropolitan Museum of Art, used in

accordance with the provisions for free use established by the donor. It may be

found at: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/37933?searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&showOnly=openAccess&

ft=mahabharata&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=3. Accessed December 27,

2019.

73 The source for this image is

The New York Metropolitan Museum of Art, used in accordance with the provisions

for free use established by the donor. It may be found at: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/21837?searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&showOnly=openAccess&ft=

mahabharata&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=5. Accessed December 27, 2019.

74 The source for this image is

The New York Metropolitan Museum of Art, used in accordance with the provisions

for free use established by the donor. It may be found at: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/254867?searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&showOnly=openAccess&

ft=iliad&offset=20&rpp=20&pos=22. Accessed December 27, 2019.

75 The source for this image is

The New York Metropolitan Museum of Art, used in accordance with the provisions

for free use established by the donor. It may be found at: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/251473?searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&showOnly=openAccess&

ft=iliad&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=12. Accessed December 27, 2019.

76 The source for this image is

The New York Metropolitan Museum of Art, used in accordance with the provisions

for free use established by the donor. It may be found at: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/247020?searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&showOnly=openAccess&

ft=iliad&offset=20&rpp=20&pos=30. Accessed December 27, 2019.